KEY ACTIVITY #4:

Use a Systematic Approach to Decrease Inequities Within the Population of Focus

This key activity involves all seven elements of person-centered population-based care: operationalize clinical guidelines; implement condition-specific registries; proactive patient outreach and engagement; pre-visit planning and care gap reduction; care coordination; behavioral health integration; address social needs.

Overview

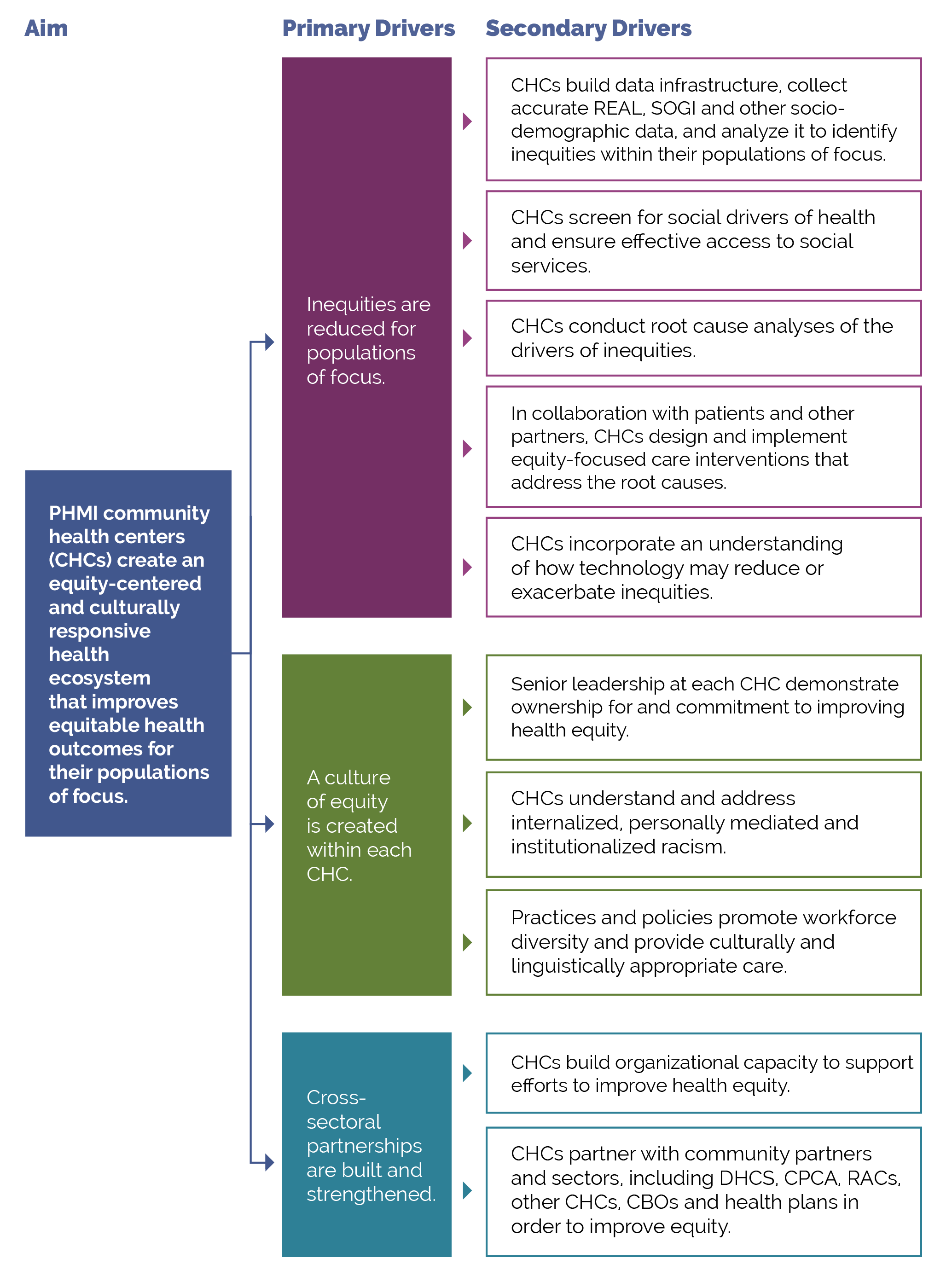

This activity provides guidance for a systematic evidence-based approach for identifying and then reducing inequities for children. It focuses on the first primary driver in PHMI’s equity approach: Reduce inequities for populations of focus.

FIGURE 9: PHMI EQUITY DRIVER DIAGRAM

Your practice is likely achieving better outcomes with certain populations or subpopulations and worse outcomes with others. Inequitable outcomes are often the result of social and cultural factors that serve as barriers to accessing care. They are generally most acute among persons of color, immigrants, persons speaking a primary language other than English and other populations who have been marginalized. As we work to reduce and, over time, eliminate inequitable health outcomes, we need to understand both what contributes to these different outcomes as well as factors that do not contribute to them

This includes recognizing that race is a social construct determined by society’s perception. While some conditions are more common among people of certain heritage, inequities in conditions such as cancer, diabetes and adverse maternal outcomes have no genetic basis. While genetics do not play a role in these inequitable outcomes, the extent to which inequities in the quality of care received by people of color contribute to inequitable health outcomes has been extensively documented.[1] These inequities are often a direct result of racism, particularly institutionalized racism – that is, the differential access to the goods, services and opportunities of a society by race.[2] Racial health inequities are evidence that the social categories of race and ethnicity have biological consequences due to the impact of racism and social inequality on people’s health.[3] It is also critical to recognize that we have policies, systems and procedures that unintentionally cause inequitable outcomes for racial, ethnic, language and other minorities, in spite of our genuine intentions to provide equitable care and produce equitable health outcomes.

Improving your practice’s key outcomes for each population of focus requires a systematic approach to identifying equity gaps (e.g., who your practice is not yet achieving equitable outcomes for) and then using quality improvement (QI), co-design, systems thinking and related methods to reduce these equity gaps.

Identifying and meeting patients’ social needs are key drivers of reducing inequitable health outcomes. We provide additional guidance in this key activity on how to both reduce inequities and meet patients’ social health needs.

Access to the data required to identify and monitor inequities, as outlined in the key actions below, is fundamental to this activity.

Relevant HIT capabilities to support this activity include care guidelines, registries, clinical decision support (modifications required to consider disparate groups), care dashboards and reports, quality reports, outreach and engagement, and care management/care coordination (see Appendix E: Guidance on Technological Interventions).

EHRs have the ability to capture basic underlying socioeconomic, sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) and social needs-related data but may in some cases lack granularity or nuances that may be important for subpopulations. Mismatches between how the UDS captures REAL data versus how EHRs capture or MCPs report data can also create challenges. This may require using workarounds to capture these details. It is also important to ensure that other applications in use that may have separate patient registration processes are aligned. Furthermore, tracking inequities in accessing services not provided by the health center may also require attention to data sources or applications outside the EHR.

Health centers should also be alert to the potential for technology as a contributor to inequities. For example, patient access to telehealth services from your practice may be limited by the inequitable distribution of broadband networks and patient financial resources (e.g., for phones, tablets and cellular data plans). The Techquity framework can be a useful way to structure an approach to ensure that technology promotes rather than exacerbates inequity.

Language, literacy levels, technology access and technology literacy should also be considered and assessed against the populations served at the health center.

Action steps and roles

1. Build the data infrastructure needed to accurately collect REAL, SOGI, social needs and other demographic data.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: data analyst.

- Race, ethnicity and language (REAL)

- Sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI)

The PHMI Data Quality and Reporting Guide provides guidance and several resources for collecting this information. According to this guide, the initial step in addressing inequities is to collect high-quality data that fosters a holistic view of patient characteristics and needs. This entails incorporating REAL data, demographic data (age, SOGI, geography) and social needs data. By collecting and monitoring this information, healthcare practices can gain valuable insights into inequities in access, continuity and health outcomes. Steps 2 to 4 below provide more information on this process.

Collecting REAL information allows practices to identify and measure inequities in care while also ensuring that practices are able to interact successfully with patients. This is done by understanding patients’ unique culture and language preferences.[4] KHAQuality.com has a toolbox that assists with REAL data collection.

The Uniform Data System Health Center Data Reporting Requirements (2023 Manual) provides detailed guidance on REAL and SOGI. Note: While UDS does not currently require that practices report on the specific primary language of each patient, practices should make an effort to identify and record each patient’s primary preferred language since UDS reporting still requires languages other than English to be reported.

Accurate data collection requires appropriate fields and options in the EHR and other employed technologies, as well as appropriate human workflows in collecting the data. Staff responsible for data collection should be continuously trained and assessed for best practices in data collection, including promotion of patient self-report.

In addition, practices should work to ensure that patients understand the importance and use of this information to help them feel comfortable with supporting its collection. High rates of “undetermined” or “declined” responses in these fields may be indicative of the need to train staff in how to ask these questions and to communicate the importance of the information and how it will be used to improve the healthcare the patient receives. An example of how this was incorporated into a practice was Lyon-Martin Community Health Services partnering with its EHR provider in order to build trust with disclosing this type of data.

Collecting this data is important, especially to obtain a complete picture of health for patients who identify as transgender. There are certain risks and condition indicators that are gender specific, which impact how clinicians provide care to a patient. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health has provided further guidance regarding standards of care related to gender diversity.

2. Use the practice’s EHR and/or population health management tool to understand inequitable health outcomes at your practice by stratifying your data.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: data analyst.

This includes reviewing your care gap report/care registry and being able to stratify all of the following:

- Core measures for the population of focus.

- Supplemental measures for the population of focus.

- Process measures for the population of focus.

Stratify this data by:

- REAL.

- SOGI.

- Other factors that can help identify subpopulations in need of focused intervention to reduce an equity gap (e.g., immigrants, people experiencing homelessness, etc.).

This is not a one-time event, but rather a continuous process (see step 13 below). It should be done in tandem with step 3 below.

Each practice should define the frequency of review and use of its registry to stratify data. In early use, the stratified data will support the identification of areas of inequity and allow for interventions to be prioritized.

3. Screen patients for social needs.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: care team.

Key Activity 17: Use Social Needs Screening to Inform Patient Treatment Plans provides guidance on screening patients for health-related social needs and how the information can begin to be used to inform patient treatment plans, including referral to community-based services. This is not a one-time event, but rather a continuous process. It should be done in tandem with step 2 above.

4. Analyze the stratified data from steps 2 and 3 to identify patterns in inequitable outcomes within the population of focus.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: data analyst, QI leads and care team.

Analyze the stratified data from steps two and three to identify patterns in inequitable outcomes.

This includes:

- Utilizing tools to examine, visualize and understand disparities across different populations or subpopulations.

- Data over time (using run charts).

- Exploring trends, patterns and significant differences to understand which demographic groups will require a focused effort to close equity gaps.

Update your practice’s measurement strategy so your practice’s improvement efforts remain centered around advancing equitable outcomes. Some examples include creating specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, time-bound, inclusive and equitable (SMARTIE) goals and updating your process and outcome measures so you can understand differences by REAL or SOGI indicators. See Appendix C: Developing a Robust Measurement Strategy for more.

This is not a one-time event but rather a continuous process (see step 13 below). Periodic review of stratified data allows for recognition of gap closures and emergence of new disparities.

5. Conduct a root cause analysis for each subpopulation that the practice does not yet have equitable outcomes for.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: multidisciplinary team.

Select root cause analysis approaches that work best for the equity gap you are closing include:

- Engagement with and gathering of information from patients affected by the health outcome in your root cause analysis (see step 6).

- Brainstorming.

- Systems thinking (understanding how interconnected social, economic, cultural and healthcare access factors may be impacting the health outcome).

- Tools that rank root causes by their impact and the feasibility of addressing them (e.g., a prioritization matrix and/or an impact effort matrix).

- Visual mapping of root causes and effects (e.g., fishbone diagram).

- Focused investigations into selected root causes to gather qualitative data through interviews, surveys or focus groups with the subpopulation of focus.

Present the findings to a broader group of stakeholders to validate the identified root causes and gain additional insights. Incorporate the stakeholders’ feedback and refine the analysis, as needed.

6. Partner with patients to develop insights that will help you develop successful strategies.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: care team and people with lived experience (patients who are members of the population[s] of focus).

Using one or more human-centered design methods, such as focus groups, 7 - Stories, Journey mapping, etc. (see links to these methods below), work with members of each population of focus to better understand:

- Their assets, needs and preferences.

- Cultural beliefs, including traditional healing practices.

- Beliefs and level of trust in healthcare generally and in the topic of focus specifically (e.g., cancer screening, immunizations, behavioral health, etc.).

- Barriers to accessing care.

- Barriers to remaining engaged in care.

- Trusted sources of information or communication mechanisms for this population.

- Their ideas for improving health outcomes.

The patients you partner with for this and other steps in this key activity may be part of a formal or informal patient group and/or identified and engaged specifically for this equity work.

7. Identify key activities that address or partially address the root causes of the identified equity gaps.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: care team and people with lived experience.

Based upon the insights your practice has developed for a population of focus and your root cause analysis, determine which of the key activities in this implementation guide could address or partially address the equity gap. This could also include making physical adjustments to the environment in order to make the practice more welcoming or culturally responsive.

Most of the key activities in this guide either explicitly address an equity challenge or can be adapted to better address an equity challenge. Examples of key activities that can be adapted to reduce identified equity gaps include (but are not limited to):

- Key Activity 20: Strengthen Community Partnerships.

- Key Activity 11: Screen for Chronic Conditions.

- Key Activity 8: Proactively Reach Out to Patients Due for Care.

- Key Activity 17: Use Social Needs Screening to Inform Patient Treatment Plans, such as providing a referral for one of the CalAIM Community Supports.

- Key Activity 18: Coordinate Care.

- Key Activity 22: Continue to Develop Referral Relationships and Pathways.

- Key Activity 23: Strengthen a Culture of Equity.

8. Develop new strategies/ideas to address the identified equity gaps.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: care team and people with lived experience.

If one or more of your root causes cannot be addressed fully through key activities in this guide, use one or more human-centered design methods (see resources below) to develop ideas to improve health outcomes and reduce inequities among people with chronic conditions.

Developing these ideas is best done with representatives who are diagnosed with a chronic condition (as they have expertise and experience that may be missing from the practice’s care team). Compensating these patients and community members for time spent on improvement activities is a best practice. During this brainstorm, you are developing ideas without immediate judgment of the ideas in an effort to generate dozens of potentially viable strategies.

Selected resources on human-centered design and co-design

- Center for Care Innovations (CCI) Human Centered Design Curriculum via CCI Academy.

- IDEO’s The Field Guide to Human-Centered Design.

- IDEO’s Design Kit: Methods.

9. Determine which strategies to test first.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: care team and people with lived experience.

Steps 7 and 8 above help your practice identify existing key activities and generate new ideas.

There are many ways to prioritize ideas. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement often recommends a priority matrix.

If you have organized your key activities and new ideas into themes or categories, you may choose to work on one category or select one to two ideas per category to work on.

The number of key activities and/or new ideas that you prioritize for testing first should be based on the team’s bandwidth to engage in testing. Therefore, it is critical to determine the bandwidth for the team(s) that will be doing the testing so that you can determine how many ideas to test first.

10. Use quality improvement (QI) methods to begin testing your prioritized key activities and new ideas.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: care team and people with lived experience.

Nearly all the key activities and all of your new ideas will require some degree of adaptation to use them within your practice and to be culturally relevant and appropriate to your patients.

Use plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles, generally starting as small as feasible (think in ones — e.g., one clinician, one hour, one patient, etc.) and becoming larger as your degree of confidence in the intervention grows.

Whenever testing a key activity or new idea, we recommend that the practice:

- Use PDSA cycles to test your ideas and bring them to scale. See more information on PDSAs below in the Appendix C: Developing A Robust Measurement Strategy.

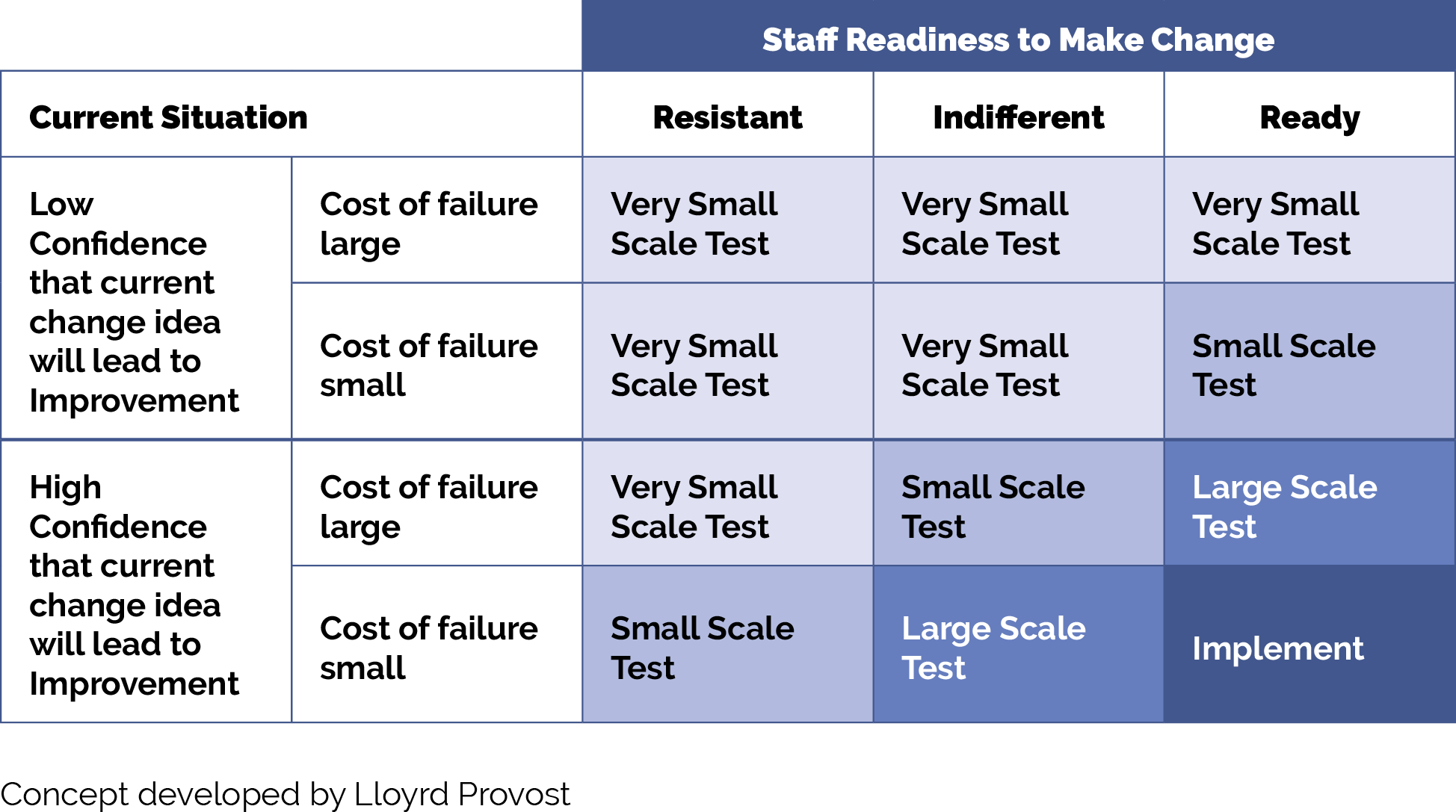

- Generally, start with smaller-scale tests (e.g., test with one patient, for one afternoon, in a mailing to 10 patients, etc.). Use the chart titled How Big Should My Test Be? in the Implementation Tips section below to help you decide what test size is most appropriate.

Develop or refine your learning and measurement system for the ideas you are testing. A simple yet robust learning and measurement system will help you understand improvements, unintended secondary effects and how implementation is going.

By working out the inevitable challenges in the idea you are testing using a smaller-scale PDSA cycle, ultimately, the improvement activity will work better for patients and be less frustrating to the care team. Testing and refining also can eliminate inefficient workarounds that occur when a new process or approach is imposed onto an existing system or workflow.

Select resources on Quality Improvement (QI)

Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Quality Improvement Essentials Toolkit, which includes:

- Cause and effect diagrams.

- Driver diagrams.

- Failure modes and effects analysis.

- Flowcharts.

- Histograms.

- Pareto charts.

- PDSA worksheet.

- Project planning form.

- Run charts.

- Scatter diagram.

IHI’s Videos on the Model for Improvement (Part one and Part two).

11. Implement (bring to full scale and sustain) those practices that have proven effective.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: care team.

Once an idea has been well tested and shown to be effective on a small scale, it is time for your practice to “hardwire” the idea, approach or practice into your daily work. Consider using the MOCHA implementation planning worksheet to think through:

- Measurement.

- Ownership.

- Communication (including training).

- Hardwiring the practice.

- Assessment of workload.

Sometimes implementation may require that you update your protocol and/or policies and procedures for the populations of focus.

12. Once you have tested, refined and scaled up the initially prioritized ideas, begin testing other ideas.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: care team and people with lived experience.

This might include going back to ideas that were elicited previously but were not initially prioritized for implementation. You might also move through the testing steps above to generate and prioritize new ideas or adapt ideas to better serve additional subpopulations of focus.

13. Establish formal and informal feedback loops with patients and the care team.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: care team.

To help ensure that your practice’s ideas are meeting the needs of patients (and their families), helping to reduce identified equity gaps, and are feasible/sustainable for your practices, it is important to have both formal and informal feedback loops.

For patients (and their families), feedback loops might include:

- Sharing ideas with the population of focus to gather feedback and ensure accuracy before testing.

- Getting feedback from patients directly after testing new ideas with them (and incorporating their feedback into your next test).

- Patient satisfaction surveys (or similar).

- Follow-up calls with a subset of patients to understand what works well and what could be improved.

- Patient focus groups.

- Having the practice’s patient advisory board or similar provide feedback.

- For the care team, feedback loops might include:

- Existing or new staff satisfaction/feedback mechanisms.

- Regularly scheduled meetings/calls to get staff feedback on processes, methods and tools.

14. Continually analyze your data to determine if your efforts are closing equity gaps.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: care team.

This includes regular (at least monthly) review of the stratified measures for all of the following:

- Core measures for the population of focus.

- Supplemental measures for the population of focus.

- Process measures for the population of focus.

- Social needs data.

- Any additional measures collected as part of your testing and refinement effort.

Share the data with patients to both show your work to decrease known equity gaps and to solicit ideas for closing them.

Implementation tips

- When testing a change idea (either a key activity or new idea) for your practice to address a known equity gap, the size of your test scope or group is critical.

- We recommend starting with a very small test (e.g., with one patient or with one clinician) or a small test (e.g., with all patients seen during a three-hour period by one clinician) unless you are certain that the change idea (key activity or test) will lead to improvement (with little or no adaptation for your practice), the cost of a failed test is extremely low, and staff are excited to test the change idea.

- As you learn from each test what is (and is not working), you can conduct larger-scale tests and tests under a variety of conditions. While at first glance this would appear to slow down the implementation effort, starting small and “working out the kinks” as you progressively work to full scale actually save time and resources and are much less frustrating for your patients and care team. The visualization below provides guidance on how big your test should be.

FIGURE 10: HOW BIG SHOULD MY TEST BE?

Resources

Endnotes

- Institute of Medicine. 2003. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in healthcare. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10260

- Improving Health Equity: Build Infrastructure to Support Health Equity. Guidance for Healthcare Organizations. Boston, Massachusetts: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2019. (Available at www.ihi.org)

- Chadha N, Lim B, Kane M, Rowland B. Institute for Healing and Justice in Medicine; 2020. https://belonging.berkeley.edu/race-medicine

- REAL Data Collection Toolbox [Internet]. KHA; 2022 [cited 2023 Dec 18]. Available from: http://www.khaquality.com/Portals/[4]/Resources/HQIC_REAL%20Data_Collection_Toolbox.pdf