BUILDING THE FOUNDATION

Business Case Guide

Version 2 – January 2025

Version 2 – January 2025

©️ 2024 Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, Inc.

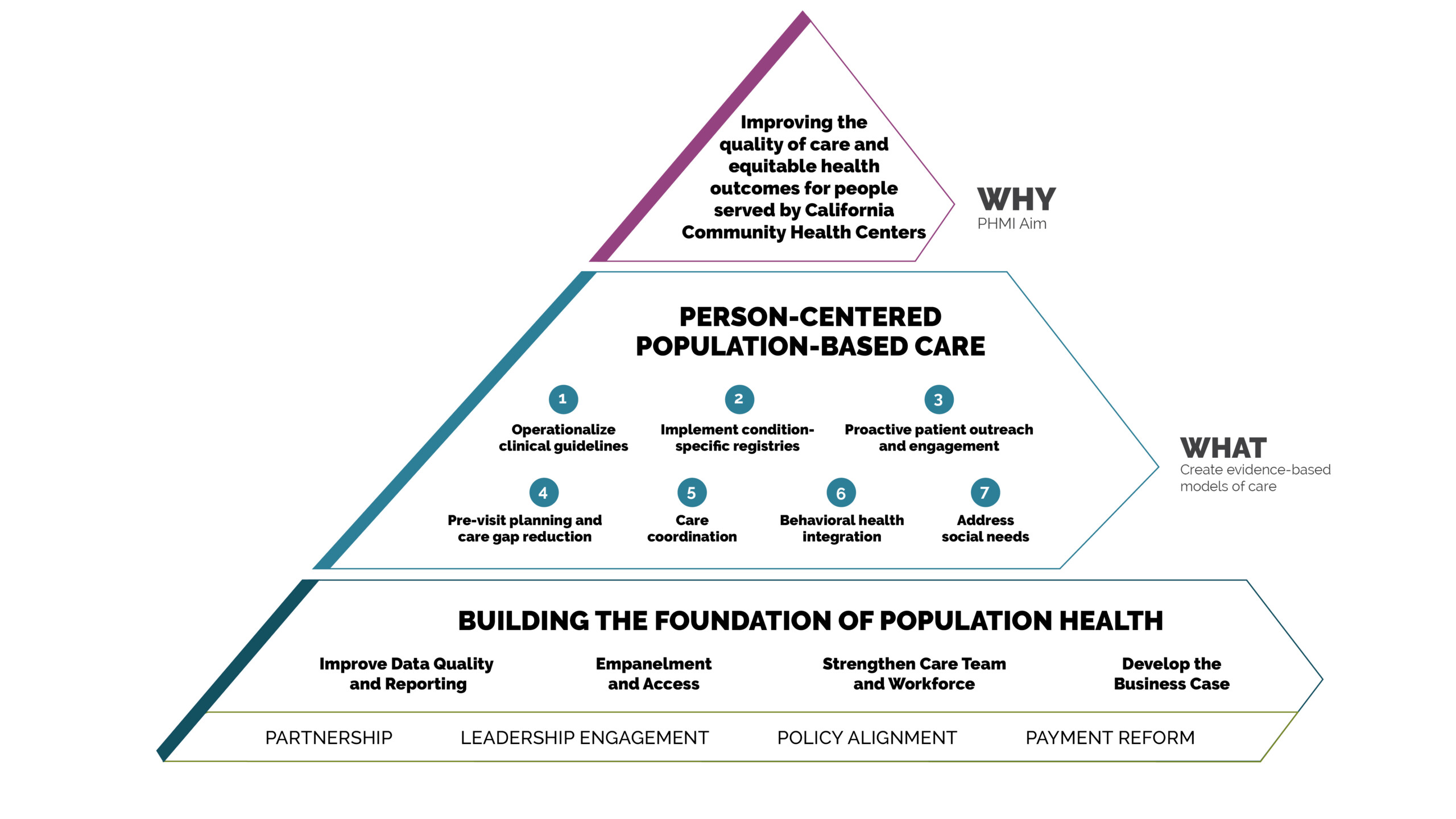

Providing high-quality population-based primary care requires a team and sustainable financing right from the start to ensure success. A clear understanding of your unique business dynamics contributes to your financial wellbeing and aids you in taking advantage of new opportunities to create revenue while navigating around challenges like rising healthcare salaries.

At the heart of the Population Health Management Initiative (PHMI) work in this domain is the Business Case Tool. This guide enables a multidisciplinary team of leaders within a community health center to model various approaches to care and anticipate the financial outcomes with a reasonable amount of certainty for individual clinical sites. Although this guide is designed especially for the unique payment considerations of health centers, working through your business case is important for all primary care practices.

Using the Business Case Tool, a health center can monitor the financial health of their population health management model throughout implementation by comparing actuals to projected outcomes and intervene early when the data indicates that modifications to the approach are needed. Additionally, the business case tool serves as a template for calculating return on investment and deciding whether to implement the PHMI model of care in additional sites and/or expand its scope in the pilot site(s).

These guides are designed to be helpful as part of an organized quality improvement strategy, with the goal of supporting substantive cultural, technological and process changes that improve population-based care.

Enterprising practices can take on this work on their own with internal champions, including quality improvement, clinical and program leaders. They are often supported by practice facilitators, coaches or external consultants who help primary care practices improve population health management.

The central content of the guide is organized into a sequenced set of evidence- or best practice-based key activities that, when applied to your local clinical context, can lead to improved ways of working. An on-site leader or champion can motivate peers and adapt the content in this guide for your setting, size, patient population and context.

The Business Case Guide helps organizations develop a financial model for an optimized care team to support population health management. It helps determine the expenses and potential revenues that result from investing in and implementing population health management. The guide includes adaptations for community health centers and their specific payment mechanisms. If your practice is not a health center, some parts of this guide and the accompanying tools may not directly apply to you, but can be adapted for your use.

Though the specific business case for improving population health management varies for each organization based on the patient composition and payer mix of practices, in general, the goal of this guide is to leverage high-performing care teams to proactively support patients and families in improving their health. Using provider time appropriately, reducing waste and rework, avoiding expensive emergency department visits, and leveraging value-based payment arrangements are all components of building the business case for population health management.

The Business Case Tool helps facilitate the planning for operational change. It’s a sophisticated Excel spreadsheet designed to simulate changes to primary care practice staffing and models of care in order to help estimate the resulting financial implications. Using this tool will enable a multidisciplinary team of leaders to model various approaches to care, and anticipate the financial implications with a reasonable amount of certainty.

For organizations interested in Going Deeper, additional content is available on moving further into value-based care through capitated payment or shared savings arrangements to support the adoption of new care team roles and service delivery modes. Finally, the guide covers business case topics On the Horizon.

This guide was developed specifically for community health center leadership from different disciplines (financial, clinical and operations) who are working to set goals, develop an action plan and realize it over time. Involving representatives from leadership positions across your organization in both the design of the business case and decisionmaking that impacts their work can be transformational in and of itself. We recommend you engage:

In addition to your business case, there are advantages for your operations and culture to integrating clinical and financial teams early on. This might be the first time you bring these two teams together. It is an important step in prompting a new way of thinking within your organization, and is a valuable activity within itself.

By using the Business Case Tool, you will be able to tackle important issues and answer critical questions about the appropriate care team model as you go, including:

As you build your business case, consider these revenue stream options:

Although it is never too late to develop a business case, the biggest payoff comes from initiating the process during the planning phase of your initiative, and then utilizing it throughout your population health management journey to validate the projections and adjust the model over time in response to actual financial performance.

We recommend you begin developing your business case even before your population health management approach has been finalized. The power of your business case lies in the ability to help practice leadership identify a financially sustainable approach for a unique site—before committing to a specific model or set of resources.

Maintaining the tool over time will enable you to objectively monitor how the projections play out and determine the financial impact, allowing you to make midcourse adjustments.

Ideally, you build periodic assessment of your business case model and test scenarios using the Business Case Tool as part of your annual budgeting cycle.

The key activities below will guide you through the process:

After working through the key activities, you will be able to:

As you begin, a few notes about using the Business Case Tool:

To get started with the Business Case Tool, we recommend following these steps:

This includes, at a minimum, the chief financial officer, analyst, clinical representative from care management, medical director or chief medical offer, and an operations lead.

The team should align around revenue streams for CHCs in California, including APM 2.0, and how you plan to use the Business Case Tool. For more information, please see the Summary of California CHC Revenue Streams.

For context, note that opting to continue in a fee-for-service environment rewards improvement in population health by increasing billable visits through:

Under the fee-for-service financial structure, existing and expanded care team members are assigned duties that allow the billable member of the care team to concentrate their efforts on visit tasks that they are uniquely qualified to perform.

Alternatively, electing to participate in APM 2.0 rewards a care team for attracting and managing a larger panel of assigned members through the most efficient, yet clinically appropriate, use of the full care team. In this financial model, existing and expanded care team members assume clinical responsibilities within their scope of training and license, and only complete a warm handoff to a billable member of the care team if clinically required.

For example, adding nurse triage in a fee-for-service environment might add cost (salary and benefits) without corresponding revenue to offset the cost, such as billable visits. Alternatively, adding nurse triage in a capitated environment might add cost (salary and benefits) but creates the ability to manage a larger panel size, enhancing financial sustainability.

Your team is now ready to use the Business Case Tool, informed by your shared understanding of the CHC’s preliminary decision regarding APM 2.0 participation. The Business Case Tool is an Excel workbook composed of the following eight tabs.

Tab |

Purpose |

|---|---|

Instructions |

Orientation to the purpose and use of the tool. |

Staffing and Salary Cost |

Input of salary and benefit costs by staff position. |

Users, Visits, Revenue |

Physical and behavioral visits and revenue by payer category in 2022. |

Administrative Costs |

Site specific administrative costs (fixed and variable) and corporate overhead allocation to the site. |

Incentive Information |

Pay-for-performance incentive payments by metric and payer, earned and potentially earned. |

Historical Financials |

Site-specific all-source revenue, expenses and calculation of net margin. |

PHMI Expenses and Grants |

PHMI project-specific non-care team expenses and grant revenue. |

PHMI Optimal Care Team |

PHMI recommended core team and expanded care team modeling. |

Ideal Care Team Simulation |

Financial modeling using recommended or modified expanded care team with or without triggering change in scope and rebasing of PPS rate and with or without adoption of capitated APM. |

As you begin to use the tool, we recommend following this sequence of steps:

As the care team strategies are implemented, it is important for the health center to monitor their financial outcomes to assess how well the projections made in the Business Case Tool align with actual expenses and revenue. This proactive monitoring will enable the health center to intervene in a timely way and make midcourse corrections if the actuals are off target.

Operationalizing health equity in practice means getting serious about aligning your operational model with the needs of specific subpopulations. Building your business case will help you consider how to distribute resources to effectively reduce health disparities. Consider the following as you think about revenue streams, service lines, care models, team composition and skill sets needed to achieve health equity:

Assess how organizational equity goals are reflected in operations.

Examine the resource allocation required to reach patient subpopulations that need additional support. You may, for example, need to increase your budget to enhance the work of community health workers on specific teams.

Assess the impacts of different payment models on the sustainability of your equity-based work. Consider where savings or additional revenue from one service line may support the sustainability of another service line.

Remember to periodically realign your budget and operational decisions with your equity priorities as you learn new information.

Organizations interested in business strategies to support population health should consider embracing opportunities to adopt capitated payment, where practices are paid a fixed, per-patient monthly amount to cover all primary care services. This type of fixed payment enables practices to make investments in care team roles and modes of patient interaction that may not be billable in a traditional fee-for-service environment, generating new opportunities for patient engagement and improvement in outcomes.[1][2] Capitated payment alone, however, will not drive improvements in population health.

In order for payment reform to have the greatest effect on population health, payment must be designed to drive behavior change for the health system, administrators, providers and care teams. The Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network offers a widely used framework for classifying alternative payment models for healthcare.[3] This framework describes a continuum of options for healthcare payment, from the traditional fee-for-service approach to alternative payment models linked to quality through upside-only or upside and downside risk, all the way to payment built entirely on population parameters.

Studies of value-based payment implementation over the past decade suggest that small shifts away from fee-for-service payment produce only small effects, and that both intentional model design and focused accountability are critical for leveraging payment reform to improve patient experience, outcomes and equity.[4] Although there is a significant opportunity to create mutual leverage between alternative payment and care model transformation, succeeding with this strategy requires clinical vision, effective leadership with appropriate financial, clinical and administrative capabilities, and organizational resources to build the operational competencies to rethink how primary care is delivered.[5][6]

Despite the substantial care improvement opportunities enabled by capitation, there is an increasingly complex and uneven payment reform landscape for healthcare organizations considering participation. Opportunities for and participation in payment reform tend to be uneven at both the state and health center levels, with more capitation and value-based payment activity present in some states than others, and lower participation in value-based payment arrangements among smaller health centers.[7] Participation in clinically integrated networks or independent provider associations is an increasingly common strategy for both smaller and larger organizations to achieve the scale needed to successfully enter into value-based payment arrangements.[8] For additional information check out this report from Center for Health Care Strategies, which provides an overview of options and pilots to consider.

Building on existing opportunities for entering into value-based payment arrangements with managed care plans, there are emerging opportunities for California community health centers to shift to capitated payment and quality-based incentive programs through the Department of Health Care Services. These opportunities include the federally qualified health center Alternative Payment Methodology (APM) going live in June 2024, and the Equity Practice Transformation (EPT) program. In addition, providers may also be able to participate in a variety of new care models and payment reform efforts associated with California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Cal (CalAIM), the five-year plan launched in 2022 to transform California’s Medicaid program. Changes coming to care delivery and payment range from Enhanced Care Management (ECM) and Community Supports (also known as In Lieu of Services) for people with complex medical and social needs to streamlining and integrating behavioral health benefits for people with mental health and substance use disorder challenges. To read about the bold and wide-ranging Medi-Cal plans to improve payment and care delivery, visit the Department of Health Care Services website.

As community health centers consider adopting capitated payment that is linked to quality, engagement of the assigned-but-not-yet seen population is a critical step for successful performance on quality metrics that include these patients in the denominator population. This is a big shift in measurement and mindset for many organizations, and will require strong partnership with managed care plan partners to assure clarity about their patient assignment process.[9] Accounting for the assigned-but-not-yet-seen population may have important implications for your organization’s approach to empanelment as well, and should be considered when developing strategies to manage supply and demand. Working to engage this population provides an excellent opportunity to deploy community health workers in their capacity as outreach and enrollment agents, and to partner with community-based organizations to reach the people who are not coming in for visits.[10]

Improving quality in the context of capitation also requires providers to think expansively about how care is delivered, including adopting new care formats, new team roles, and new ways to plan, manage and coordinate care for the patient population.[11][12] Although capitation creates an opportunity to improve care, care transformation must be intentionally designed and implemented to realize the full potential of payment reform.[13] For more information about care model redesign, read and explore the PHMI Care Teams and Workforce Guide.

Dr. Art Jones has 27 years of experience as a primary care physician and chief executive officer at a Chicago area community health center. The health center was an early adopter of managed care, successfully operating under a partial capitation payment system for all ambulatory and emergency room services and shared savings for inpatient services since the early 1990s. He was the architect for the first capitated federally qualified health center (FQHC) alternative payment methodology in the country in 2001.

Q: What do you think community health centers should focus on as they consider the business case for primary care transformation?

A: Move off the fee-for-service chassis. Capitation gives you the flexibility to optimize the full care team, and really optimize providing options to access care in a way that is most timely and convenient for patients. Once you take the handcuffs off your providers and care teams, they can be really creative, but they are so used to hearing, “No, we can’t do that. That’s not financially sustainable.”

We didn’t have the luxury to start dreaming about the ideal care team. We didn’t have an offset investment. We just focused on how we can take our existing staff and redeploy them in new ways. We figured out how to use the community health workers, do home visits, really think outside of the fee-for-service box. It can be done. You can’t go in with the assumption that any of this is an add-on; it’s got to be a total redesign. You can’t expand and do everything, you have to really think about what can be done differently.

Q: As organizations move to capitated payment and consider going even further with value-based payment arrangements, what kind of care transformation opportunities do you see?

A: The best leverage for capitated payment is in the context of total cost of care. I am the chief medical officer of Medical Home Network in Illinois, a clinically integrated network and accountable care organization with 180,000 Medicaid lives. We started in 2014 and got certified by the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) for care management, started with shared savings arrangements, created an agreement to move to shared risk in three years, and are now in global risk contracts. Our care managers are employed and geographically situated within the community health centers so that they can really function as a core part of the care team, and have succeeded in generating over $100 million in savings since 2014.

We were able to make investments in nonmedical services, such as a fitness center, a preschool, housing, post-prison transitions, and an urban farm that raises tilapia and healthy greens.

We are also using community health workers to support our patients who have hypertension, diabetes and depression, and we are really thinking about how they change access to care. We were having trouble with staff recruitment and retention for medical assistants. So, we took a look at the MA work experience: call people from the waiting room, gather chief complaints and vital signs, and repeat all day long. What if, instead, we say, you’ve built a relationship with these patients and I will give you half a day a week where you are going to be the community health worker supporting the patients who are self-monitoring for hypertension. You are going to teach them about taking their blood pressure, talk about medication, self-management, etc. Then we are going to have a hypertension clinic once a week, where we see six patients in an hour instead of three in partnership with their community health workers. You can even do it by telehealth, and if you are capitated, then you don’t need to see the patients every month, you can just see the ones who aren’t well controlled and you don’t have to worry about video and audio requirements because you are capitated.

We can have the patients come sit in our waiting room at a time that is convenient for us and not for them, and keep getting the same results. Or, we can actually take a step back and see how we can do things differently.

Q: What do you find particularly exciting relating to payment reform for advancing health equity right now?

A: Care management of high risk individuals is a health equity issue. The way to address health equity is to recognize that we can’t treat everyone the same; we have to determine who is high-risk, and go beyond looking at disease burden, demographic and claims data. We have to look at the social conditions and enabling services that can interfere with any health improvement efforts. We have a health-related social needs screener who we have been using since 2014. Now, we have a lot of rich information in our data warehouse, and use artificial intelligence to identify who can most benefit from high risk care management. In other words, not just focusing on the people on dialysis or chemotherapy.

Hiring is also critical to equity. We were having trouble hiring community health workers and said, “Where’s our workforce? They are out in the waiting room.” We created an initial training where we paid $500 for a week of training and then we bring those people into the hiring pipeline. We just started doing this in the last year because we had people who had been laid off during the pandemic, and when we tried to bring them back, they said they prefer to work at Amazon. What does that say about the quality of their employment conditions? So, we are really looking at how to hire differently and become a better and more equitable employer.

Q: When you look on the horizon to the future of payment reform, where payment arrangements may account for activities beyond the walls of the clinic, what interesting things do you see happening with payment reform and community partnerships?

A: This is really hard. It’s hard to tease out the impact of interventions on reductions to total costs. It’s easy to do PCP attribution; a good next step would be to include behavioral health, and then take a similar approach to community-based organizations. If we track the data of where patients are going, we can think about incentivizing the community-based organizations to make sure kids come in for well child visits, and adults are coming in for cancer screenings and diabetic visits. But we have to start by learning how to do this well with behavioral health.

To peer at the horizon in business planning and strategy for population health, you can simply look to categories three and four in the HCP-LAN framework and move into value-based payment arrangements, which are organized around upside and downside risk and shared savings. This extends all the way to accepting global risk for managing the total health and total healthcare costs for a population of patients.

Since the formation of the Center for Medicaid and Medicare Innovation (CMMI), which was created at the Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) by the Affordable Care Act, many different programs have been launched to trial the effects of category three and four payment reforms at both the federal and state levels.[14] The primary care transformation efforts facilitated by CMMI in this first decade have shown mixed results, with “few programs demonstrating meaningful increases in the availability of primary care, reductions in costly forms of utilization or improvements in quality.”[15]

Although there are mixed results overall, there are examples from around the country of community health centers successfully entering into category three and four value-based payment arrangements with varying approaches to population and global payment and a range of downside risk agreements. Some of the critical strategies for success include taking a stepped approach to adopting alternative approaches to payment, and making strategic investments in care delivery and data management. This includes adding clinical pharmacists, community health workers, and diabetes educators to teams, and new technology supports, such as tools for telehealth, timely health information exchange, and population data management.[16]

For community health centers considering value-based payment arrangements as a lever to promote health equity, consider designing and implementing a linked set of strategies that provide mutual reinforcement between new approaches to care delivery, including a focus on person-centered, culturally and linguistically responsive, integrated care, as well as equity-focused and intentional payment model and measurement design. You may also want to consider integrating a social risk adjustment approach to your payment arrangements, in addition to adjusting for medical complexity. If you are going to be paid for improving engagement and outcomes, social risk adjustment will help to account for the additional effort required to successfully engage and improve health for people living with complex and challenging circumstances.

In the first decade since CMMI was created by the Affordable Care Act, a great deal of experimentation and learning has been achieved. CMMI recently announced a new 10-year initiative, Making Care Primary (MCP), which will build on the results of the past decade. Making Care Primary will be tested in eight states and will provide opportunities for provider organizations to take a gradual approach to population-based and value-based payment adoption, with a focus on building infrastructure for behavioral health, social services, and specialty care coordination and integration. While only eight states are participating in Making Care Primary, this latest investment from CMMI points to national trends in primary care payment reform and care delivery transformation nationally.

Recommended citation: Population Health Management Initiative. Arthur Jones, Andrew Rudebusch, Hunter Schouweiler, and Leslie Brooks. Business Case Implementation Guide. In: Coleman K and Singer A, editors. Building the Foundation Implementation Guide Series. 1st ed. Oakland, CA: Kaiser Permanente, Health Management Associates, and Pyramid Communications; 2023.

Acknowledgments: This document was created by the Population Health Management Initiative (PHMI), a California collaboration of the Department of Health Care Services, Kaiser Permanente and Community Health Centers. We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of these partners and the Regional Associations of California along with the many other academic, health plan and consulting partners who shared their expertise and insights freely as we collaboratively designed the initiative and created these guides.

Individual reviewers and content contributors to the first edition of the Building the Foundation Implementation Guide Series: Jennifer Sayles and Elise Pomerance (KP PHMI); Palav Barbaria, Yoshi Laing, David Tian, Jeff Norris and Karen Mark (DHCS); Allie Budenz and Cindy Keltner (CPCA); Jeanene Smith, Catherine Knox, Nancy Kamp, Ethan Norris, Leslie Brooks and MaryEllen Mathis (Health Management Associates); Anne Tillery, Sarah Starr, Karis Cady, Candace Jackson, Josh Daniel and Denise Rhiner (Pyramid Communications); and Veenu Aulakh.

With additional contributions from: Pyramid Design Team and Kaiser Permanente PHMI team.