©️ 2024 Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

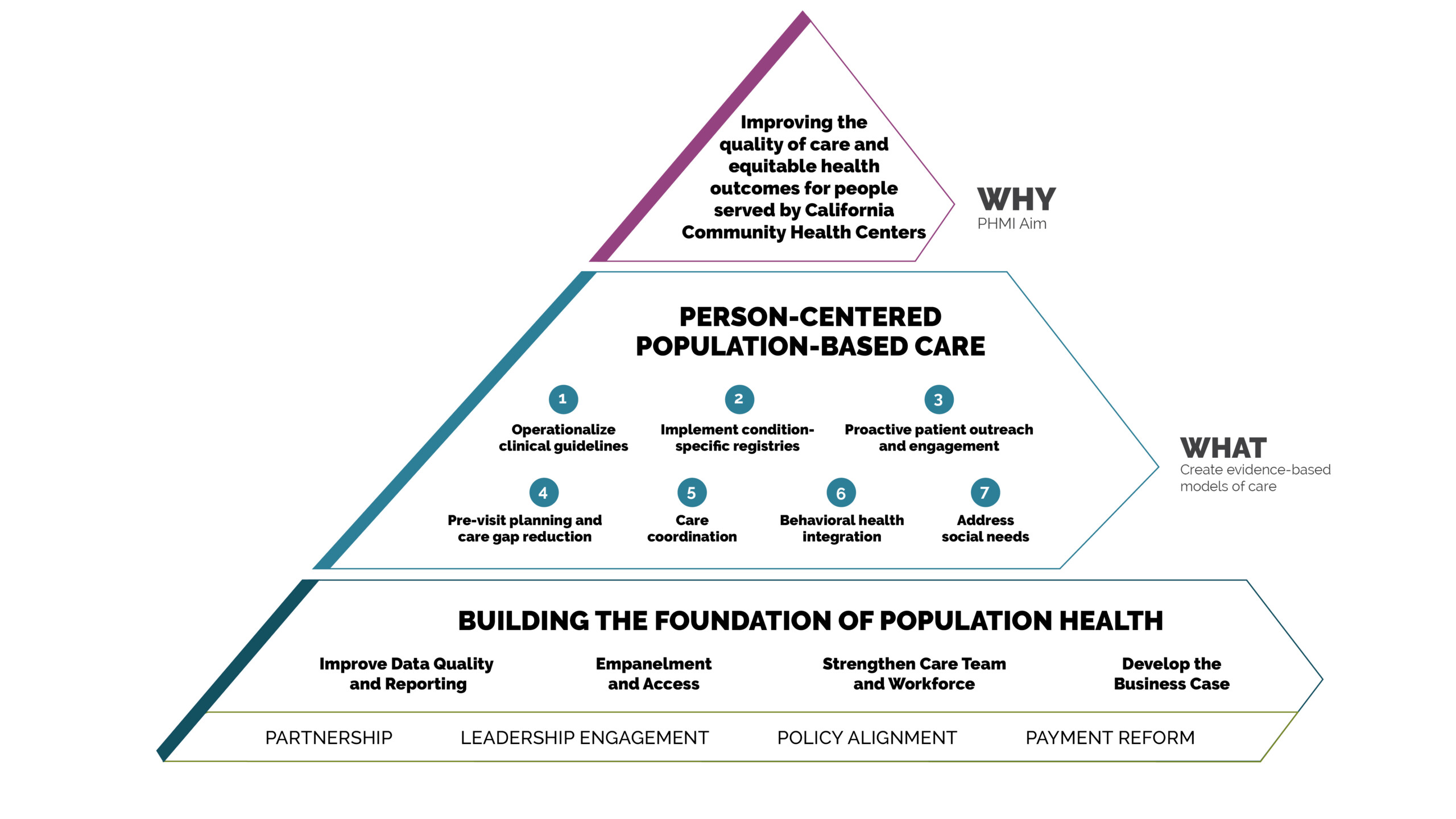

Empanelment is the act of attributing individual patients to individual primary care providers (PCPs) and care teams with sensitivity to patient and family preferences.[1] This process of attribution transforms the entire population of patients served by a primary care practice into distinct subpopulations that can be managed by clearly identified primary care providers and care teams.

Designating groups of patients to be cared for by individual providers and care team functions as a cornerstone for high-performing primary care and population health management.[2] By developing clearly defined subpopulations, empanelment enables:

- Population management by care teams.

- Continuity and the development of therapeutic, trusting relationships between the care team and the patient, an essential component of effective primary care.

- Provider/visit supply and demand management.

- Data-driven decision making about access, schedule templates, population health metrics, and clinical redesign.

- Care team accountability for results.[3]

Creating a population health management approach in primary care requires a cultural shift towards proactive population-level monitoring and intervention while also maintaining the quality of individual patient interactions and patient care. Empanelment is a key driver of this cultural change: organizing patients into groups that primary care teams can take responsibility for managing is both a foundation and an ongoing goal of effective population health management.

Optimizing empanelment requires additional operational changes beyond the organization of patients into subpopulations. The shift from addressing immediate needs with provider visits to a focus on managing population health with proactive and preventive care is facilitated by:

- Right-sized panels.

- Patient choice of PCPs.

- Empanelment-aware scheduling that balances continuity with promptness.

- Messaging systems that foster continuity.

- Tools that support responsiveness to patients’ needs, even for patients without appointments.

These guides are designed to be helpful as part of an organized quality improvement strategy, with the goal of supporting substantive cultural, technological and process changes that improve population-based care. Enterprising practices can take on this work on their own with internal champions, including quality improvement, clinical and program leaders. They are often supported by practice facilitators, coaches or external consultants who help primary care practices improve population health management. The central content of the guide is organized into a sequenced set of evidence- or best practice-based key activities that, when applied to your local clinical context, can lead to improved ways of working. An on-site leader or champion can motivate peers and adapt the content in this guide for your setting, size, patient population and context.

This guide offers technical and relational guidance on how to implement empanelment, which involves attributing individual patients to individual primary care providers and care teams with sensitivity to patient and family preferences.[4] The guide addresses key considerations for empanelment, including change management, staffing, organizational policies and procedures, and health information technology requirements, as well as concrete steps for conducting initial patient assignment and ongoing population management using panel-level data.

For organizations interested in Going Deeper, additional content is available on the relationship between empanelment and patient-centered access, as well as empanelment and outreach to members assigned by managed care who have not yet been seen by the practice. Finally, the guide covers empanelment topics On the Horizon, such as the impact of behavioral and social health integration, virtual care, and artificial intelligence tools for managing supply and demand.

Empanelment is foundational to primary care population health management, and should be adopted by any practice working to strengthen proactive and systemic health improvement for the population they serve. Investing in change management is critical for success, and proactively collaborating with providers and care teams throughout the empanelment process is an essential foundation for sustainable, team-level accountability and engagement in panel-based population health.

Like any significant practice change, implementing empanelment requires engaged multidisciplinary leadership to succeed. Critical roles needed to lead the implementation of empanelment include:

- Clinical leadership, like a chief medical officer, to design and facilitate provider engagement in initial panel assignment and ongoing panel management activities.

- Health information technology (HIT) leadership, such as a chief technology officer or chief clinical informatics officer, to identify and support analytics staff to collaborate on developing the necessary reports and HIT infrastructure for initial empanelment and ongoing empanelment maintenance.

- Quality improvement (QI) leadership, like a QI director or manager, to partner with clinical and HIT leadership to support the cultural changes and process improvement required to implement and sustain empanelment.

- Financial leadership, like a chief financial officer, to collaborate in determining how the organization will resource the key functions of a panel manager, including whether to redeploy existing staff or develop and hire a new staff position.

- Patients and families should serve as critical partners in implementing and sustaining empanelment in order to optimize relationship-driven care. Partner with patients to collaboratively design effective approaches for both initially identifying and changing PCPs, as well as addressing tensions between access and continuity in ways that are acceptable to your local community.

Investing in change management is critical for success, and proactively collaborating with providers and care teams throughout the empanelment process is important for sustainable team-level accountability and engagement in panel-based population health. Leaders may use this guide to gain actionable insights and ideas to address the technical, cultural and human elements of this transformational approach to managing a primary care population.

Key Activities

These key activities offer a concise set of tasks that your practice can work through to initiate or improve a sustainable, data-driven and person-centered approach to empanelment. You may already have completed some of these activities, in which case you can start wherever makes the most sense to you. You may also find that some of these tasks are iterative, and will need to be revisited over time as you develop systems to not only launch but also sustain a practice-wide approach to empanelment.

The key activities below will guide you through the process:

- Invest in role clarity, leadership engagement and staff participation.

- Develop data and reporting capabilities to implement and manage empanelment and panel data.

- Conduct initial patient assignment and supply and demand balancing.

- Develop ongoing strategies for managing empanelment and population health.

After working through the key activities, you will be able to:

- Identify a panel manager.

- Conduct initial patient assignment and balance supply and demand.

- Implement ongoing panel management by regularly monitoring empanelment reports and making panel adjustments.

Key Activity #1: Invest in role clarity, leadership engagement and staff participation.

While at first glance empanelment might seem like a set of technical and formulaic activities for population segmentation and attribution, successful execution requires far more than rendering clear designations in the clinical information system. Empanelment can drive the primary care paradigm from reactive care provided to individual patients to proactive, accountable care provided at the population level; actualizing this paradigm shift requires strong leadership and the involvement of all the critical stakeholders, from patients to providers, care teams and data analytics partners.

1. Assign responsibilities for managing empanelment to a new or existing leader with a clear description of duties.

- Centralize operational leadership of the empanelment process by designating an individual to be the panel manager. The panel manager may be a newly hired role, or these duties may be added to an existing and well suited role. See below for key responsibilities for empanelment operational leadership.

- Position the panel manager with adequate authority to collaborate with senior leaders to define and guide empanelment strategy within the organization, as well as with data and HIT leaders to provide panel data for care teams to drive population health management.

- Prioritize and integrate empanelment data such as overall empanelment rate, continuity, panel size variation and appropriate schedule utilization into the organization’s performance dashboard for routine reporting and improvement.

The person assuming these duties may vary depending on practice size and organizational structure. This role could be fulfilled by a director of quality improvement, a data analyst or a project manager.

Suggested responsibilities for the empanelment leader:

- Generate periodic reports for key performance indicators (KPIs) such as continuity, retention and PCP changes.

- Generate operational reports such as clinician capacity (panel fullness), urgent/ same-day appointment availability, and third next available appointment (TNAA).

- With operations leader(s), ensure that the number of new patient slots align with the degree of panel fullness.

- With operations and medical leaders, create PCP teams and care teams.

- With medical leadership, review PCP change requests to ensure patients understand their role in PCP choice and that their reasons for excess change requests are understood and addressed.

- Educate all staff and providers on the importance of empanelment, access and continuity.

- Assess the impact of requests for changes in part-time status for clinicians.

- Assess the impact of and support medical and operational leaders in making decisions on cross coverage, temporary coverage, and movement of whole or partial panels.

- Manage panel weighting activities.

2. Proactively engage providers and teams as partners in the empanelment process.

Empanelment and panel management in a primary care practice substantially reorganizes the practice’s approach to service delivery and requires staff participation and proactive change management to succeed. Check out the Supporting Change section for additional tips on change management for empanelment.

A clear communication, engagement and education strategy to facilitate primary care provider and care team participation in the empanelment process is critical for organizational success. Involving PCPs and care team members in the organizational approach to empanelment drives a sense of ownership for the process and accountability for the team’s panel as a cornerstone of relationship-based care and population health management.[5], [6]

Key change management and partnership steps may include:

- Provide targeted training so that role groups within the practice understand the purpose of empanelment and the implications of their role.

- Engage PCPs as workgroup leaders to help set parameters, make strategic decisions and guide the empanelment process.

- Develop and support standard work for teams to conduct panel management activities, including setting aside time for this critical population health function.

3. Develop consensus on policies, procedures and key empanelment parameters, and ensure clear and consistent communication and training on new expectations to staff.

General Empanelment Policies and Procedures

To ensure consensus, practices should develop an empanelment policy that is reviewed and approved yearly by executive leadership and the board.[7] The policy should:

- Clearly define the purpose and process of empanelment.

- Describe key roles and responsibilities.

- Define procedures (both initial and ongoing empanelment) for establishing and assessing panel size, opening and closing panels, and other key empanelment steps.

- Codify the patient’s right to make both the initial PCP selection and PCP changes, as well as the frequency that PCP assignment is verified with the patient.

- List required reports, sample workflows and scripts for staff.

Defining Primary Care Provider Teams

Well-developed multidisciplinary primary care teams can serve as a multiplier of primary care supply, thereby increasing the ability of the practice to meet demand.[8]

Although well organized teams with efficient workflows can increase supply, parttime clinical status of providers is a common challenge for practices and will create additional complexity for managing supply, demand and continuity. Some potential solutions include:

- Setting organizational policies that define a minimum full-time equivalency (FTE) for providers and/or set a minimum FTE threshold for maintaining a primary care panel.

- For providers with low clinical FTE, consider deploying those staff to episodic care environments (float, urgent care, PTO coverage, etc.).

- Forming PCP teams with two to three part-time PCPs to create a team with an overall status of 1.0 to 2.0 FTE altogether.

- Measuring continuity and other panel measures (e.g., care gap closures) for both the individual providers and the PCP teams.

Key Activity #2: Develop data and reporting capabilities to implement and manage empanelment and panel data.

Empanelment is a data-intensive process and requires adequate health information technology (HIT) resources for both initial implementation and ongoing maintenance. Resources are required for information system configuration and the personnel to manage, report and refine panel data.

1. Identify HIT leadership and team resources to serve as partners in designing, validating and providing ongoing reporting relevant to empanelment.

Practices may choose an analytics specialist to serve as the lead on empanelment. If an operational or clinical staff member is chosen instead, recruit adequate data and analytics partnership so that the necessary validated business intelligence reports are available ongoingly. While the specifics may vary significantly between organizations, establishing adequate partnership and commitment of HIT resources is critical to the success of empanelment and panel-driven population health management.

2. Develop and monitor reports.

Although there are a wide range of reports that may be useful for managing empanelment, practices should prioritize developing reports that correspond with Empanelment Implementation Guide 10 their own empanelment process measures. Empanelment process measures can help reduce the percentage of patients without an assigned primary care provider, as well as increase the frequency of patients seeing their own provider and providers seeing their own patients. In addition to using empanelment process measures, you should consider developing the capability to report all of your quality data at the panel level so that care teams have specific, actionable data to use for quality improvement and population health management purposes.

Suggested empanelment metrics include:

- Empanelment: Percentage of patients who are assigned to a provider and care team.[9]

- Numerator: Number of patients with a PCP attributed by the practice.

- Denominator: Total number of established patients, including all managed care assigned patients.

- Suggested initial target: 90%.

- Continuity (Patient Perspective): Percentage of patient visits with attributed provider and care team.[10]

- Numerator: Number of patients seen by provider X who were empaneled to provider X.

- Denominator: Total number of primary care visits for patients empaneled to provider X.

- Suggested initial target: More than 80%.

- Appropriate schedule utilization (Provider Perspective Continuity): Percentage of visits that provider sees patients assigned to them.[11]

- Numerator: Number of patients seen by provider X who were empaneled to provider X.

- Denominator: Number of patients seen by provider X.

- Suggested initial target: This depends!

Goals for appropriate schedule utilization can vary by provider and practice. If a provider is temporarily covering for another provider who is on vacation or leave, it may be appropriate for the other provider’s patients to be scheduled with them. However, if provider X has a full patient panel but is seeing a significant number of other provider’s patients, this may lead to provider X’s actual patients not being able to schedule with provider X in a timely manner. This creates a snowball effect as provider X’s patients are scheduled with other providers or are scheduled too far into the future.[12]

3. Establish a process to reconcile health plan assignment data.

As alternative payments become more closely linked to population parameters set by health plans, health plan assignment of patients to providers becomes more consequential to both quality metric performance and revenue. Discrepancies often occur between payer assignment and provider-level attribution of empaneled patients. In a fee-for-service environment, these discrepancies may simply create irritation and confusion for the patient and the provider. In the context of value-based payment, the problems caused by this mismatch in payer assignment and practice attribution increase.[13] Working with payers to reconcile assignment and attribution mismatch is an important step in establishing a value-based payment arrangement.

Key Activity #3: Conduct initial patient attribution and supply and demand balancing.

To develop provider panels, the practice must conduct initial patient attribution, as well as develop a process for regular review and adjustment to ensure there is a balance of supply and demand. Managing supply and demand requires opening and closing panels based on capacity. A simple count of the patients in a panel will too often overestimate or underestimate the level of effort required to deliver primary care to the patients in the panel. Capacity management may be improved by using a panel weighting system to reflect the intensity of effort required to care for different segments of the population.

While no panel weighting system can be perfect, using a good enough weighting system addresses provider concerns and can avoid incentivizing volume-based care with frequent visits as a protective mechanism against a larger panel.

1. Attribute all patients to a provider panel and confirm attribution with providers and patients; review and update panel attribution on a regular basis.

Initial empanelment methods are well described, and while the methods require close attention to detail, they do not require any sophisticated calculations.[14] Empanelment methods should be used when there is either no PCP/patient association or when a reset is needed to respond to low accuracy of existing PCP/ patient associations.

Initial empanelment should account for patient and family preferences and established PCP relationships, although gathering every patient’s preference individually is not generally practical. General communication at the time of initial empanelment or reset with a clear and explicit process for changing PCPs is generally adequate for patient participation in empanelment.

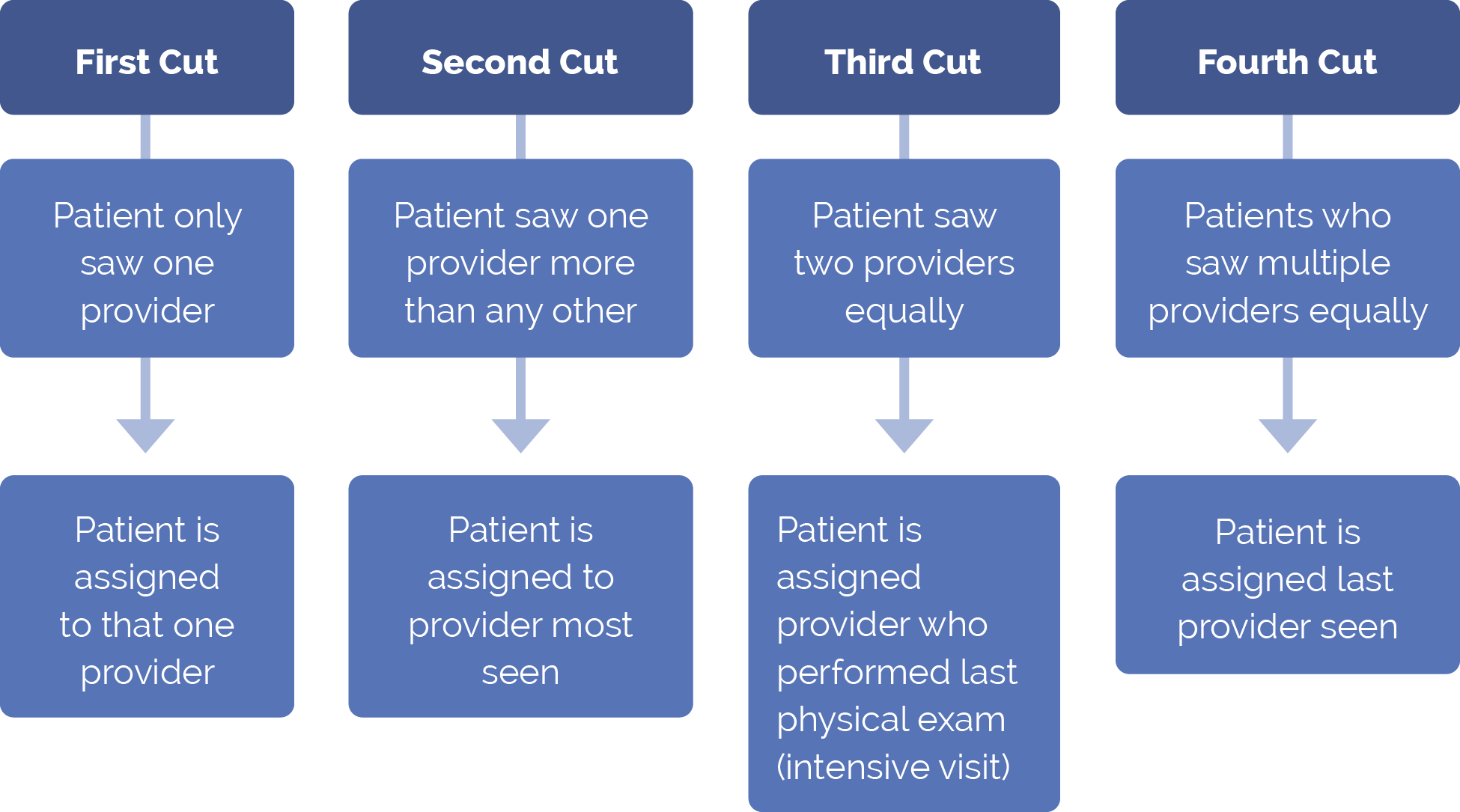

Two common methods for initial or reset empanelment are the four-cut method and the one-cut method.

Four-Cut Method

The four-cut method is a set of four sequential processes. Any patients not empaneled per an earlier process are subject to the next process. The sequential processes are conducted using appointment data from the past year:

FIGURE 1: FOUR-CUT METHOD

Single-Cut Method

In the single-cut method, each visit in the prior two years is weighted, and the patient is empaneled to the provider with the highest sum of the weighted visits.

2. Right-size panels according to provider capacity.

Once assigned, practices should develop and implement a process to keep panels right-sized to provider visit supply. This process may include managing demand by weighting panels and closing panels to new patients, as well as increasing supply by optimizing team roles and creating new and more efficient ways to deliver care. Patient preference and movement between panels should also be considered, as described below.

The Importance of Panel Size

Determining the appropriate panel size is important for:

- Accurately managing supply and demand.

- Getting support for empanelment from PCPs by establishing shared parameters for fair and rational workload distribution.

- Ensuring adequate access for the population served.

Calculating Panel Size

Panels should be calculated by dividing the total time that any given provider will work based on provider agreements of clinical sessions per week and weeks per year of paid time off (PTO) by the average number of visits per patient per year. In addition to this simple calculation, practices may want to calculate weighted panel size in order to account for variation in demand between patients.

Determining New Patient Slots Per Provider[15]

FIGURE 2: PANEL FULLNESS AND NUMBER OF NEW PATIENTS

Percent Fullness of Panel |

Number of New Patients per Session14 |

|---|---|

<25% |

5 |

25-50% |

4 |

50-75% |

3 |

75-95% |

2 |

95-105% |

1 |

>105% |

0 |

The number of new slots in a provider’s schedule (per session or per week) should be closely related to the fullness of their panel. Some practices use patient weighting systems that account for patients who have not been seen in an extended period of time, e.g., all patients seen in the past eighteen months or two years are counted in the panel. When using this approach, practices should use the retention rate to determine how many new patients should be added. The number of new appointments is then determined by the percent fullness as shown in figure 2. Accounting for retention both improves accuracy of supply and demand projection and incentivizes PCPs to keep patients engaged and active at an appropriate level.

Patient Choice and Movement Between Panels

Managing and monitoring movement of patients between panels is an essential aspect of empanelment and should be overseen by the leader responsible for empanelment. Patient-requested PCP changes are especially critical, but there may be other reasons for panel churn, such as provider staffing changes or rebalancing of overloaded panels. Although panel fullness may impose some constraints, patients should be offered their choice of providers whenever possible, and should be informed of the internal PCP change processes and the goal of fostering positive, healing relationships. The change process should include clear documentation of the reason for the patient change request so that leaders may address patient concerns appropriately.

Key Activity #4: Develop ongoing strategies for managing empanelment and population health.

Empanelment as a population health management strategy requires ongoing attention and maintenance with respect to both accuracy and integrity of panel size and assignments, as well as team-level use of panel data for panel management.

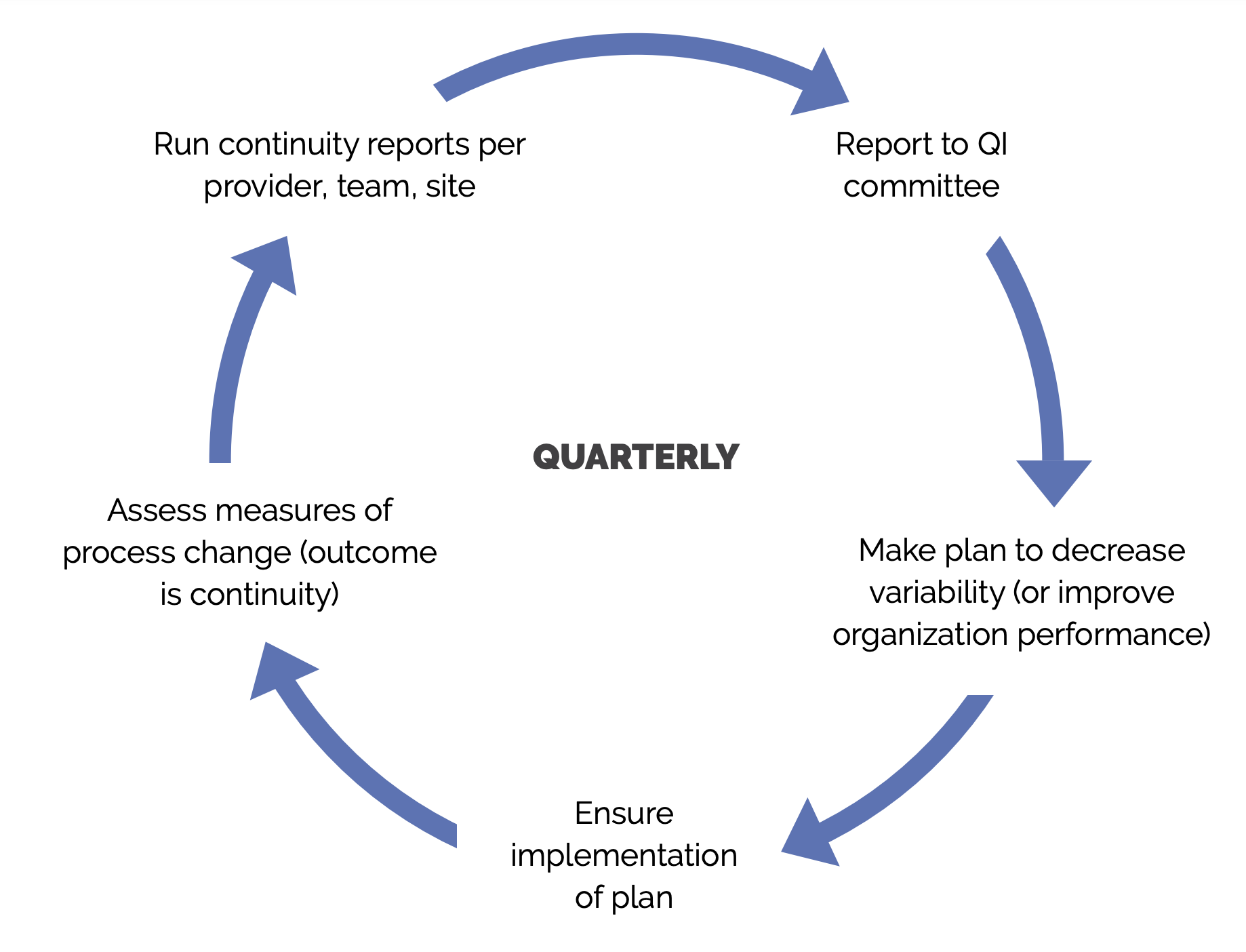

1. Use continuous quality improvement methods to check and adjust empanelment policies and procedures.

Improving relational continuity is one of the primary goals of empanelment; measuring both provider and patient continuity drives the improvement of relational care. Although a continuity goal of 100% is not realistic, as some appointments will inevitably occur with providers besides the patient’s own PCP, practices should set a continuity goal that reflects their care environment, including patients’ need to balance continuity with promptness of care.

Higher rates of both continuity and appropriate schedule utilization are likely to increase provider satisfaction, improve quality metrics and diminish avoidable excess utilization, but are hard to achieve and sustain. A practice with part-time PCPs, low chronic disease burden, and a higher percentage of non-infant children may be able to produce good results with a lower (~ 70%) continuity rate. In comparison, a practice with mostly full-time providers and many patients requiring frequent visits for chronic conditions might require an 85% or greater continuity rate to deliver good results. A goal of 80% is a reasonable place to start for most practices.[16]

Retention of patients at the practice improves continuity at a system level. Retention is difficult to measure for the whole population since many patients only need infrequent primary care interactions, and their retention may be unknown for a year or two after their last interaction with the practice. Retention, however, can be measured on a shorter timeline for subpopulations expected to have frequent clinical contact with the practice, such as infants, pregnant people and patients with some chronic conditions.

FIGURE 3: CONTINUITY AND RETENTION PERFORMANCE IMPROVEMENT[17]

2. Use panel data and registries to proactively contact, educate and track patients by disease status, risk status, self-management status, community, and family need.

Once practices have established empanelment, care teams can use the data available for their panel to monitor care gaps, conduct proactive outreach and engage the patients on their panel for preventive and chronic disease care. This set of activities is particularly important for patients with high or rising risk who can be grouped into populations with shared traits for engagement in relevant care activities.[18] Using panel data for these outreach and care engagement activities is essential to effective population health management overall.

Advancing Equity Through Empanelment

Health equity, the principle that each person has a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible, is enhanced by improving access to the conditions and resources that strongly influence health. The process of empanelment can help shape the resources and conditions that improve health equity, including promoting continuity and care team access, the availability of granular population data, and language and racial concordance between patients and providers. When exploring how to advance health equity through empanelment, practices may consider:

Use panel attribution to increase racial and linguistic concordance.

- The Urban Institute offers research and a rationale for including racial and linguistic concordance as part of empanelment: Racial, Ethnic, and Language Concordance between Patients and Their Usual Health Care Provider.

Conduct and analyze panel-level appointment data to design improvements to continuity and access.

- This brief by the American Hospital Association Center for Health Innovation provides guidance on how to use data to identify, investigate and intervene to address health disparities: Using Data to Reduce Health Disparities and Improve Health Equity.

- The Commonwealth Fund offers case studies that show how health care centers were able to use patient data to design interventions that improve care and reduce disparities: How New Mexico’s Community Health Workers Help Meet Patient Needs.

Act on panel data to design care teams that respond to the whole-person needs of that patient population, including consideration of their cultural and sociopolitical experiences and barriers to care.

- This toolkit from the Center for Care Innovations provides several tools to support care team design and functioning as they move toward health equity: CP3 Population Health Toolkit.

- University of Washington’s Center for Health Workforce Studies provides an exploratory review of the ways in which healthcare workers can be best utilized in team settings to achieve health equity: How are Health Care Workers Utilized in Health Equity Interventions? An Exploratory Review.

Supporting Change

Despite the importance of empanelment, both technical and cultural challenges can make empanelment difficult to implement and sustain. Although some challenges may arise, practices can launch, measure and maintain empanelment so that every care team is responsible for a population of patients and the patients in their population know their PCP and care team.

Critical success factors to prepare for empanelment include:

- Allocating sufficient resources, including:

- Designating leadership responsibility for managing and maintaining empanelment.

- Dedicating time for all providers and care teams to learn about the foundational elements of empanelment.

- Dedicating time for a subset of provider and care team staff to participate in empanelment and panel management workgroups.

- Making data analytics or business intelligence resources available to develop, validate and refine key empanelment and panel management reports.

- Redeploying or hiring care team staff to conduct panel management activities.

- Developing ongoing organizational processes to monitor and improve empanelment and panel management for population health improvement.

- Reducing part-time staffing for PCPs or creating staffing minimums.

- Reducing turnover of PCPs and care team staff.

- Accounting for residency program churn and designing for continuity where possible.[19]

- Seeking revenue arrangements that reduce dependence on visits and promote payment for population management.

- Partnering with health plans to address incongruent assignment data.

- Recognizing and addressing practice patterns that make continuity difficult: high no-shows, high proportion of same-day or urgent appointments, and saturated schedules.

Engaged leadership is the first building block in high performing primary care[20] and drives the success of all transformational efforts. As with many care transformation efforts, the success of empanelment relies on leadership in multiple domains.

Successful practices mobilize leadership on at least three levels:

- Executive leadership develops and shares a mission-driven strategic vision for change and makes organizational investments in resourcing the change efforts.

- A clearly designated operational leader with well defined responsibility and authority guides the day-to-day efforts of creating operational change.

- Clinical and care team champions promote change with their peers by bringing attention, enthusiasm and direct experience to the operational change efforts.

As an initial step, organizational leaders should develop and share a clear and compelling vision for change, including an overview of:

- What: Clear explanation of the definition and essential components of empanelment.

- Why: Alignment between empanelment and organizational mission and priorities, for example, describing the connection between empanelment, relationship-driven care and population health.

- How: Anticipated process, timeline and role implications for empanelment and panel management at the organization.

Change management for initial empanelment should include setting expectations with providers and care teams that the initial goal is not perfection but a good enough starting point to launch an ongoing, collaborative process to improve size, accuracy and management of the panels. Involve care teams with decision-making and implementation of empanelment to promote shared ownership and accountability.[21]

Going Deeper

Connecting Empanelment with Patient-Centered Access

Patient-centered access requires balancing both prompt availability of services and continuity with the patient’s own care team. Like empanelment, patient-centered access is an important building block of high functioning primary care[22] and is significantly impacted by the forces of supply and demand. Long waits for appointments cause delays in diagnosis and treatment, and may undermine patient satisfaction and perceptions of quality. While providers can improve access by scheduling patients with any available provider, relational discontinuity diminishes trust and the establishment of healing relationships.[23]

With a set of linked strategies, practices can successfully manage supply, demand and continuity using both empanelment and access tools. Strategies for success will depend on engaged leadership, adequate business intelligence resources and a systematic approach to monitoring and intervention on metrics relating to both promptness and continuity.

There may be times when practices must restrict access to new patients when the needs of established patients exceed the supply of provider time. Closing panels to new patients is often troubling and deeply countercultural for practices. This is especially true for health centers that have always operated with a mandate to serve everyone, regardless of their circumstance. While closing panels to manage the balance of supply and demand may cause heartburn in safety net practices, excessively large panels will also cause many familiar problems, including:

- Discontinuity and disruption to relational care.

- Long waits for appointments.

- Patient attrition.

- Provider burnout.

For a variety of reasons, many practices have struggled with the demand for primary care exceeding supply. They have adopted a range of strategies for addressing this imbalance, which include new technologies and formats for delivering care, care team enhancement to increase supply, and patient engagement strategies to reduce unnecessary demand. Practices have also been on the leading edge of many innovations to primary care delivery and have made bold investments to enhance the efficiency of care.

As all of these efforts improve efficiency and access to care, panel sizes can increase accordingly. Some practices have also addressed excess demand by creating separate care settings dedicated to providing episodic care, such as some school-based practices and urgent care centers rather than continuity-based empanelment care. In some cases, these strategies may even improve quality measure outcomes.[24] While episodic care may serve as a complement to an empaneled primary care environment, the population health benefits of continuity on costs, utilization, quality and experience require a sustained commitment to empanelment.[25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32]

For wide-ranging access improvement ideas and implementation strategies, take a look at the Safety Net Medical Home Initiative Enhanced Access Implementation Guide.

Assigned Managed Care Members Not Yet Seen By the Practice

Managed care plan (MCP) members who have been assigned to the practice, but have not yet engaged as patients, are an important population to consider for empanelment. As patients assigned to the practice for primary care, these assigned-but-not-yetseen patients are included in the population basis for MCP capitated payment and P4P programs. Practices should consider how to account for these assigned-but-not-yet-seen patients in the attribution and empanelment process, including working proactively with contracted MCPs (or Independent Practice Association delegates) to reassign these patients when they are identified as receiving primary care elsewhere, have moved away, or are deceased.

Although this population has, by definition, not yet been seen by the practice, some members of this population will have primary care needs in the coming year and should be accounted for in PCP panels using a weighting strategy to adjust for their engagement status. Most practices do not empanel individual assigned-but-notyet-seen patients until contact. In order to establish an estimate of capacity based on assigned patients, add the aggregate weight of the assigned-but-not-yet-seen population to the aggregate of all providers’ panels to determine how full panels are for the practice as a whole. In many cases, practices find that they are at or near their capacity to accept new patients. However, depending on their agreements with the health plans, it is important for practices to make a proactive plan to build their capacity to accommodate assigned-but-not-yet-seen health plan members in the clinic.

In addition to accounting for the assigned-but-not-yet-seen patients in the empanelment process, practices should also develop strategies for outreach and engagement with these populations in order to shift them from not yet seen to fully engaged in primary care.[33] Potential outreach strategies include using community information exchange and health information exchange platforms to identify and learn about members of the assigned-but-not-yet-seen populations for outreach and engagement, as well as deploying expanded care team members, such as community health workers and peer support specialists, who may have enhanced community knowledge, relationships and engagement expertise.[34],[35] Of course, the quality of data provided by health plans on the assigned-but-not-yet-seen health plan members can greatly hamper or facilitate these outreach efforts. Ongoing work to improve the data sharing and partnership between managed care plans (MCPs) and practices is critical.

Voices From the Field

Amit Shah, M.D.

Dr. Amit Shah is the chief medical officer for CareOregon, a nonprofit health plan providing health insurance services to meet the health care needs of low-income Oregonians. Prior to joining CareOregon, he was the medical director for the Multnomah County Health Department. Dr. Shah has served as a board member of CareOregon, Jefferson Health Information Exchange and Northwest Regional Primary Care Association, and is currently a member of the HealthInsight Oregon board of directors. Dr. Shah received his medical training at the Drexel University School of Medicine, Philadelphia and his undergraduate degree in molecular genetics at the University of Rochester. He has a biomedical informatics certificate from Oregon Health & Science University. He is board-certified in family medicine and a member of the American Academy of Family Physicians.

The content for this Q&A was drawn from a knowledge building session on empanelment offered by the Safety Net Medical Home Initiative. The audio recording and the slides are available online: Safety Net Medical Home Initiative.

Q: How has empanelment changed your practice as a PCP?

A: As I practiced before we did empanelment, in reality, I really had no idea who my patients were. I maybe knew who walked in the door and saw me regularly. But I certainly didn’t know who my panel of patients were and, more importantly, who the people I had to outreach to were. Patients who identified me as a primary care provider didn’t necessarily know how to access me because the system was so cumbersome, and didn’t even know that I was the primary care provider. So, really, it’s the systematic way to let patients see their own PCP. And that’s one of the core principles that I want to emphasize: because we’re in the business of patient-centered medical home, it’s the business of relationships. Empanelment is a way to ensure that those patients who have identified me as their PCP, that you can ensure that continuity.

Q: How does empanelment support population health management?

A: It allows for a group of patients to be easily identified, including those who don’t come. And I really want to emphasize that as another key concept. You know, I think primary care in general, we’re in the business of direct patient visits and that has been one of the problems that we’ve had with doing things from a population care management perspective. We have to be able to outreach to those patients who aren’t choosing to come in directly. We have to find a way to outreach to those people and say, “Hey, you haven’t been in. So, how can we get you to come in? How can we get those labs done? How can we follow up on this report, and how can we outreach to you?” You can’t do that proactive management if you have no idea about the patients you are caring for.

It will allow teams to customize their service to the specific needs of the client. When you think of your organization’s population management, that’s all the patients you’re seeing. You want to get down to the panel view and have that provider team being able to look at the patient population on their panel and identify what specific needs there are. For the first time, a PCP can actually say, “Wow, I didn’t realize that I actually have an enormous amount of patients with congestive heart failure. I didn’t even realize that I had that much of a population problem with that.” You can target your work and your efforts toward that population need. We weren’t able to identify that before, and you can really drive your reports in a population-based, very specific way to the population that you’re caring for.

Q: How does empanelment help with managing supply and demand?

A: Historically, what happens is you see whoever’s on the schedule. It’s that sort of emergency room mentality, where you walk in the clinic, and you and the team just see whoever walks in the door. Some providers work hard to see everyone who needs to be seen and others don’t. That’s just the reality of it. The variability in the complexity of the patients also depended on the provider. There was no way to understand that if I’m seeing 18 people today and this provider next to me saw 20, does that mean that this person who saw 20 is better than me?

We had no idea what that meant, so we lived in that volume-based world where we just said 20 is better than 18. I think most people would agree that’s not what primary care is about. Empanelment can help us to really start driving primary care to a different type of model that’s more about the relationship and less about the volume.

Q: How do you think about the mathematics of empanelment?

A: Specifically for managing supply and demand, there is a rational formula for determining the number of patients it’s possible to take care of. You’re not trying to get down to the most exact, precise thing you can imagine because you’ll kill yourself with the numbers. You’re trying to get to a ballpark to a close enough approximation that you could start with the number of patients you think that a person’s panel could be started with. That allows for data-based decisions. So, for example, who can be open, who’s not, have we reached capacity, now we need to hire more people–or not? But you can’t just simply assign patients to a PCP and assume that’s a panel. You want to weigh by age and gender and utilization. Start simple. That can get you 80% there and land with it. And, as you evolve, you can move into some other methodology of weighting complexity, either by disease or by higher utilizers or whatever you think is more appropriate for your system.

This is about cultural change. It’s about using the evidence that’s out there, tools that are out there; you don’t have to make this up. It’s about starting simple and getting more complex as needed, but simple is always the best way to go first. It’s about getting buyin with your teams and your clinics and your providers, and understanding the real issue, which is about relationships. It’s about spending time and energy to socialize this. It’s about getting your patient input and making sure that this fits. It’s about developing the policies and procedures that support where you want to go and support this process. And it’s about leadership and management change. And I think when you think about how complicated it is, you realize, like I said in the beginning, it’s not about the math. The math is the easiest part, no matter how complicated these little equations seem. The math is the easiest part. It’s the other stuff that’s the hard part. So, if you could work on spending the time on the other things, the math part comes very easy.

Q: What do you think is most important for supporting change with empanelment?

A: I want to emphasize: this does not have to be you putting the space shuttle to the moon. You don’t have to get every equation done perfectly. You need to just come up with a process. You need to be able to understand how to do it. You need to be able to look at what your population looks like. You need to be able to model it, and then you need to be able to talk about it. And what does talking about it mean? What does it mean to do this cultural shift of, now you have a panel of patients, not that you walk into the clinic and I’ve got 18 slots and I’m going to double book a couple, so Amit’s day is 20 today? Instead, my day today is Amit’s panel. My day tomorrow is Amit’s panel. My day the next day is Amit’s panel.

It’s a cultural shift, and where you’ll succeed is having an understanding of why empanelment is important, why you’re doing it to ensure continuity, why it’s important for the relationship, why is it important to do proactive management. You can do those things by creating an empanelment process and you need to have some policy and procedures around how you’re going to deal with empanelment, because it opens up a can of worms or a Pandora’s box of all these things that you never really thought about.

We had to create a panel management policy, which meant, how do you change providers? We had to come up with a policy of how many new patients you see based on the percentage full a panel is. We had to develop some strong policies around minimum staffing, and it was hard to do this. But, really, the numbers and the empanelment really showed us what we needed to do. For example, we created a minimum number of days in the clinic. We said we don’t care what your FTE is. If you’re .6, traditionally you’d work three days a week, and you’d have two days off. We said whatever your FTE is, you have to work a minimum of four days a week.

That created a lot of accountability, and it really emphasized that point that if we’re really going to believe that we can deliver this care and it’s relationship-based, then there’s gotta be some time commitment.

Q: What is most important for leaders considering empanelment in their organizations?

A: I think the ramification for leadership is that you have to have commitment from your leadership that this is the process that they believe in, and the buy-in from the leadership all the way down to the provider teams, the provider, and the patient is about the relationship. It’s a whole system-wide change, and the reason why you’re doing it is for relationship. It’s to build that relationship to be able to engage the patient, to proactively manage them, to identify the patients you’re caring for, to identify them on an individual level, a disease-specific level, be able to manage them in a populationbased level, and to be able to report on all of that. It’s to be able to paint a very different picture of the kind of care that you’re giving when you do these changes.

I’ll give you an example of how this happened in our organization. We have about 140 or so providers, and you know this was so important to our leadership, it’s so important to me that, basically, I met with every individual provider, and I reviewed this down to the nitty gritty of their panel with them. And the reason why I did that, and you could imagine how much time that took, because if there isn’t an understanding of why we’re doing it, it doesn’t matter if I send this out, and I prove the math of it, and I give them all these references–no one’s going to really listen to it or follow it. That one-on-one time that I spent with each one of them, one, it showed them what this is all about. Two, it gave the opportunity for them to give feedback because they gave great feedback that helped us. Three, it gave us that opportunity to be able to really hone in that empanelment is one of the many pieces we have to put together to create this medical home. And why do we want this medical home? We want it for relationship. We want it for better care. We want to improve quality and we want to be able to demonstrate it.

On the Horizon

The basics of empanelment have remained unchanged for many years. Evolution of the approach will likely be driven by larger forces impacting how primary care is conceptualized, delivered and paid for.

Shift to Whole-Person Care

The movement to address whole-person health in primary care has been on the rise for many years, building from integration of behavioral health to a more recent focus on systematically responding to health-related social needs in addition to physical wellbeing.[36],[37] Although there is a deep, wide and growing body of literature on the importance and impacts of responding to behavioral and social health challenges in primary care, the implications for empanelment are less well established. While demographic, diagnostic and risk score data have been used to weight panels according to anticipated utilization, these methods account for medical complexity alone.[38] There is a great deal yet to learn about accounting for behavioral health or social complexity in establishing panel risk adjustment and weighting methods. Wide variation in standards and lack of evidence about optimal panel size persist.[39],[40] As additional individual and population-level insights accrue relating to behavioral and social health risk factors, methods to adjust panel size based on patient complexity may benefit from integration of these variables.

Virtual Care Opportunities and Challenges

Historically, calculating supply and demand has been based on face-to-face interactions, even as virtual care visits have increased.[41] Even prior to the enormous expansion of virtual care accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, these activities already consumed a significant percentage of both perceived and actual physician time and capacity.[42],[43] In this environment of rapid change to telehealth implementation, saturation and reimbursement, the best formats and use of virtual primary care are still being defined.[44]

Nonetheless, as the use of synchronous telehealth and asynchronous virtual care grows, so will the importance of accounting for this workload on the supply of provider and care team time. This is an area of ongoing development, as standard methods of accounting for the total patient care workload are yet to be defined, tested and disseminated.[45] In the meantime, practices may want to consider using technology to leverage both rising insight into patient behaviors and additional options for visit formats, such as the use of machine learning by Urban Health Plan, a New York community health center, to identify patients with moderate to high risk for appointment no-shows. Following this identification strategy, Urban Health Plan developed targeted interventions to reach people for same-day conversion to telehealth visits and increased the show rate for patients most likely to miss their visits by a stunning 154%.[46]

Artificial Intelligence Implications for Supply and Demand Management

Machine learning is “the fundamental technology required to meaningfully process data that exceed the capacity of the human brain to comprehend,” where a computer model uses algorithms to learn from a large data set of examples rather than operate on the basis of discrete rules. This capability allows the model to absorb and learn from enormous data sets, thereby acquiring the ability to perform tasks far more complex than simple rules-based coding would enable.[47]

Machine learning models are well suited to improve predictive accuracy of capacity planning for empanelment by using large retrospective data sets of healthcare utilization behaviors for an accountable population. Although the efforts are nascent, the use of machine learning to enhance supply and demand management for primary care has begun, using historical utilization data to estimate the amount of primary care effort required to care for diverse population segments.[48]

In addition to improving panel weighting methods using machine learning to estimate demand, artificial intelligence is likely to significantly change the provision of primary care in a variety of ways, with implications for estimates of supply as well.[49] There are a range of ways that primary care may be augmented by artificial intelligence with some features creating greater impact on the supply of provider and care team time. For example, the use of artificial intelligence for medical advice and triage, diagnostics, digital health coaching, clinical decision-making and documentation could all free up substantial provider and care team time to interface with patients, which would have tremendous impact on the current formulae for calculating provider supply relative to patient demand.[50]

The Urban Health Plan example in the previous section is an excellent demonstration of early adoption of artificial intelligence to better understand patient demand patterns, as well as creative use of virtual care technology to diversify the formats for healthcare supply. As artificial intelligence technologies are more widely adopted and studied in Empanelment Implementation Guide 28 primary care settings, the implications for empanelment and panel management, both functionally and mathematically, will become more clear.

TOOLS AND RESOURCES

SUGGESTED CITATION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Recommended citation: Population Health Management Initiative. Greg Vachon, Deena Pourshaban, and Ariel Singer. Empanelment Implementation Guide. In: Coleman K and Singer A, editors. Building the Foundation Implementation Guide Series. 1st ed. Oakland, CA: Kaiser Permanente, Health Management Associates, and Pyramid Communications; 2023.

Acknowledgments: This document was created by the Population Health Management Initiative (PHMI), a California collaboration of the Department of Health Care Services, Kaiser Permanente and Community Health Centers. We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of these partners and the Regional Associations of California along with the many other academic, health plan and consulting partners who shared their expertise and insights freely as we collaboratively designed the initiative and created these guides.

Individual reviewers and content contributors to the first edition of the Building the Foundation Implementation Guide Series: Jennifer Sayles and Elise Pomerance (KP PHMI); Palav Barbaria, Yoshi Laing, David Tian, Jeff Norris and Karen Mark (DHCS); Allie Budenz and Cindy Keltner (CPCA); Jeanene Smith, Catherine Knox, Nancy Kamp, Ethan Norris, Leslie Brooks and MaryEllen Mathis (Health Management Associates); Anne Tillery, Sarah Starr, Karis Cady, Candace Jackson, Josh Daniel and Denise Rhiner (Pyramid Communications); and Veenu Aulakh

With additional contributions from: Pyramid Design Team and Kaiser Permanente PHMI team.

Endnotes

- Brownlee B, Van Borkulo N. Empanelment: Establishing Patient-Provider Relationships. Seattle: Safety Net Medical Home Initiative; 2013 [cited 2023 July 13]. Available from: https://www.safetynetmedicalhome.org/sites/default/files/ Implementation-Guide-Empanelment.pdf.

- Bodenheimer T, Ghorob A, Willard-Grace R, Grumbach K. The 10 building blocks of high-performing primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(2):166-71.1.

- Shah A. Knowledge Building Session:Empanelment. Seattle: Safety Net Medical Home Initiative; [September 11, 2023]. Available from: https://www. safetynetmedicalhome.org/sites/default/files/Webinar-Empanelment.pdf.

- Brownlee B, Van Borkulo N. Empanelment: Establishing Patient-Provider Relationships. Seattle: Safety Net Medical Home Initiative; 2013 [cited 2023 July 13]. Available from: https://www.safetynetmedicalhome.org/sites/default/files/Implementation-Guide-Empanelment.pdf.

- McGough P, Chaudhari V, El-Attar S, Yung P. A Health System’s Journey toward Better Population Health through Empanelment and Panel Management. Healthcare (Basel). 2018;6(2).

- Shah A. Knowledge Building Session:Empanelment. Seattle: Safety Net Medical Home Initiative; [September 11, 2023]. Available from: https://www. safetynetmedicalhome.org/sites/default/files/Webinar-Empanelment.pdf.

- National Association of Community Health Centers. Population Health Management Empanelment Action Guide. Bethesda: NACHC; 2022 [September 11, 2023]. Available from: https://www.nachc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Empanelment_PopHealth-Mgmt_Action-Guide-April-2022.pdf.

- Brownlee B, Van Borkulo N. Empanelment: Establishing Patient-Provider Relationships. Seattle: Safety Net Medical Home Initiative; 2013 [cited 2023 July 13]. Available from: https://www.safetynetmedicalhome.org/sites/default/files/ Implementation-Guide-Empanelment.pdf

- Snyder DA, Schuller J, Ameen Z, Toth C, Kemper AR. Improving Patient-Provider Continuity in a Large Urban Academic Primary Care Network. Acad Pediatr. 2022;22(2):305-12.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Care Team Member / Patient Continuity: Review of Schedule. Boston: IHI; [September 11, 2023]. Available from: https://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Measures/ TeamMemberPatientContinuityReviewofSchedule.aspx.

- National Association of Community Health Centers. Population Health Management Empanelment Action Guide. Bethesda: NACHC; 2022 [September 11, 2023]. Available from: https://www.nachc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Empanelment_PopHealth-Mgmt_Action-Guide-April-2022.pdf.

- National Association of Community Health Centers. Population Health Management Empanelment Action Guide. Bethesda: NACHC; 2022 [September 11, 2023]. Available from: https://www.nachc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Empanelment_PopHealth-Mgmt_Action-Guide-April-2022.pdf.

- National Academies of Sciences Engineering Medicine. Implementing high-quality primary care: rebuilding the foundation of health care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2021.

- Brownlee B, Van Borkulo N. Empanelment: Establishing Patient-Provider Relationships. Seattle: Safety Net Medical Home Initiative; 2013 [cited 2023 July 13]. Available from: https://www.safetynetmedicalhome.org/sites/default/files/ Implementation-Guide-Empanelment.pdf.

- Developed in 2022 through the PHMI empanelment design team process.

- National Association of Community Health Centers. Population Health Management Empanelment Action Guide. Bethesda: NACHC; 2022 [September 11, 2023]. Available from: https://www.nachc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Empanelment_PopHealth-Mgmt_Action-Guide-April-2022.pdf.

- Developed in 2022 through the PHMI empanelment design team process.

- Brownlee B, Van Borkulo N. Empanelment: Establishing Patient-Provider Relationships. Seattle: Safety Net Medical Home Initiative; 2013 [cited 2023 July 13]. Available from: https://www.safetynetmedicalhome.org/sites/default/files/ Implementation-Guide-Empanelment.pdf

- Wajnberg A, Fishman M, Hernandez CR, Kweon SY, Coyle A. Empanelment in a Resident Teaching Practice: A Cornerstone to Improving Resident Outpatient Education and Patient Care. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(2):202-6.

- Bodenheimer T, Ghorob A, Willard-Grace R, Grumbach K. The 10 building blocks of high-performing primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(2):166-71.1.

- McGough P, Chaudhari V, El-Attar S, Yung P. A Health System’s Journey toward Better Population Health through Empanelment and Panel Management. Healthcare (Basel). 2018;6(2).

- Bodenheimer T, Ghorob A, Willard-Grace R, Grumbach K. The 10 building blocks of high-performing primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(2):166-71.1.

- Schwarz D, Hirschhorn LR, Kim JH, Ratcliffe HL, Bitton A. Continuity in primary care: a critical but neglected component for achieving high-quality universal health coverage. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(3):e001435.

- Reid RJ, Scholes D, Grothaus L, Truelove Y, Fishman P, McClure J, et al. Is provider continuity associated with chlamydia screening for adolescent and young adult women? Prev Med. 2005;41(5-6):865-72.

- Gray DJP, Sidaway-Lee K, White E, Thorne A, Evans PH. Continuity of care with doctors—a matter of life and death? A systematic review of continuity of care and mortality. BMJ open. 2018;8(6):e021161.

- Raddish M, Horn SD, Sharkey PD. Continuity of care: is it cost effective? Am J Manag Care. 1999;5(6):727-34.

- Sabety AH, Jena AB, Barnett ML. Changes in Health Care Use and Outcomes After Turnover in Primary Care. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(2):186-94.

- Schafer WLA, Boerma WGW, van den Berg MJ, De Maeseneer J, De Rosis S, Detollenaere J, et al. Are people’s health care needs better met when primary care is strong? A synthesis of the results of the QUALICOPC study in 34 countries. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2019;20:e104.

- Matulis JC, 3rd, Schilling JJ, North F. Primary Care Provider Continuity Is Associated With Improved Preventive Service Ordering During Brief Visits for Acute Symptoms. Health Serv Res Manag Epidemiol. 2019;6:2333392819826262.

- Brousseau DC, Meurer JR, Isenberg ML, Kuhn EM, Gorelick MH. Association between infant continuity of care and pediatric emergency department utilization. Pediatrics. 2004;113(4):738-41.

- Nyweide DJ, Anthony DL, Bynum JP, Strawderman RL, Weeks WB, Casalino LP, et al. Continuity of care and the risk of preventable hospitalization in older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(20):1879-85.

- Arthur KC, Mangione-Smith R, Burkhart Q, Parast L, Liu H, Elliott MN, et al. Quality of Care for Children With Medical Complexity: An Analysis of Continuity of Care as a Potential Quality Indicator. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(6):669-76.

- El Sol Neighborhood Education Center. Effective Community Outreach Strategies. San Bernardino: El Sol; August 18, 2022 [September 11, 2023]. Available from: https://www.elsolnec.org/blog/2022/08/18/effective-community-outreach-strategies/.

- Center for Health Care Strategies. Recognizing and Sustaining the Value of Community Health Workers and Promotores. Hamilton, NJ: CHCS; January 2020 [September 11, 2023]. Available from: https://www.chcs.org/resource/recognizingand-sustaining-the-value-of-community-health-workers-and-promotores/.

- Harris RA, Campbell K, Calderbank T, Dooley P, Aspero H, Maginnis J, et al. Integrating peer support services into primary care-based OUD treatment: Lessons from the Penn integrated model. Healthc (Amst). 2022;10(3):100641.

- Reiter JT, Dobmeyer AC, Hunter CL. The Primary Care Behavioral Health (PCBH) Model: An Overview and Operational Definition. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2018;25(2):109-26.

- National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine. Integrating social care into the delivery of health care: Moving upstream to improve the nation’s health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2019.

- American Medical Association EdHub. Panel Sizes for Primary Care Physicians: Optimize Based on Both Patient and Practice Variables. Chicago: AMA; [September 11, 2023]. Available from: https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2702760#section-247962614.

- Paige NM, Apaydin EA, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Mak S, Miake-Lye IM, Begashaw MM, et al. What Is the Optimal Primary Care Panel Size?: A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(3):195-201.

- Mayo-Smith MF, Robbins RA, Murray M, Weber R, Bagley PJ, Vitale EJ, et al. Analysis of Variation in Organizational Definitions of Primary Care Panels: A Systematic Review. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(4):e227497

- Murray M, Davies M, Boushon B. Panel size: how many patients can one doctor manage? Fam Med. 2007;14(4):44-51.

- Arndt B, Tuan WJ, White J, Schumacher J. Panel workload assessment in US primary care: accounting for non-face-to-face panel management activities. J Am Board Fam Med. 2014;27(4):530-7.

- Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, Prgomet M, Reynolds S, Goeders L, et al. Allocation of Physician Time in Ambulatory Practice: A Time and Motion Study in 4 Specialties. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(11):753-60.

- Beheshti L, Kalankesh LR, Doshmangir L, Farahbakhsh M. Telehealth in Primary Health Care: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2022;19(1):1n.

- Kivlahan C, Pellegrino K, Grumbach K, Skootsky S, Raja N, Gupta R, et al. Calculating Primary Care Panel Size: UC Health, Center for Health Quality and Innovation January 2017 [September 11, 2023]. Available from: https://www.ucop.edu/uc-health/_files/uch-chqi-white-paper-panel-size.pdf.

- Fox A. This FQHC slashed its patient no-show rate with AI in 3 months. Portland, ME: Healthcare IT News; May 08, 2023 [September 11, 2023]. Available from: https://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/fqhc-slashed-its-patient-no-show-rate-ai-3-months.

- Rajkomar A, Yim JW, Grumbach K, Parekh A. Weighting Primary Care Patient Panel Size: A Novel Electronic Health Record-Derived Measure Using Machine Learning. JMIR Med Inform. 2016;4(4):e29.

- Rajkomar A, Dean J, Kohane I. Machine Learning in Medicine. Reply. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(26):2589-90.

- Lin SY, Mahoney MR, Sinsky CA. Ten Ways Artificial Intelligence Will Transform Primary Care. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(8):1626-30.

- Lin SY, Mahoney MR, Sinsky CA. Ten Ways Artificial Intelligence Will Transform Primary Care. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(8):1626-30.