©️ 2024 Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, Inc.

This guide provides step-by-step guidance for improving population-based care for people with behavioral health conditions with the goal of supporting substantive cultural, technological, and process changes that enhance and deepen integrated behavioral healthcare, focusing on increasing depression screening and follow-up for adolescents and adults, and depression remission or response for adolescents and adults.

This guide was designed as part of the Population Health Management Initiative (PHMI), a California collaboration of the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS), Kaiser Permanente and Community Health Centers. Much of the content is relevant and adaptable to primary care practices of all kinds working to improve the health of the populations they serve.

Improving the health of individuals and populations is only possible with adequate behavioral healthcare. Research indicates behavioral health factors moderate all components of the quadruple aim: patient experience, health outcomes, healthcare costs, and the experience of those providing care. Conservative estimates demonstrate 40% of the Medicaid population has a mental health and/or substance use disorder.[1] California Health Home data indicate that approximately 40% to 50% of Medi-Cal patients have behavioral health needs. Mental health and addictive disorders are among the top 10 most frequent diagnostic conditions among Medi-Cal beneficiaries whose health challenges lead them to be in the top 5% of healthcare costs. Additionally, data demonstrate that psychosocial problems, a primary cause of frustration for primary care providers in safety net settings, drive 70% of all medical visits.

Primary care systems are the de facto mental health system in the United States, with more than 80% of psychotropics prescribed by primary care providers. Separating behavioral health from primary care has many challenges, including a 10% follow-through rate when patients are referred off-site for behavioral healthcare. Further, research in California indicates six in 10 patients would rather discuss behavioral health issues with a professional at their primary care facility than with one located off-site.[2]

These factors and other robust research on healthcare outcomes have driven the growth of integration of behavioral health services with primary care. Currently, all federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) in California have some level of integrated behavioral health services. The largest barrier to robust integrated behavioral healthcare (IBH) services and improvements in population behavioral health for most health organizations is the wide gap between behavioral health (BH) needs and available resources. The BH provider shortage is severe[3][4] and most practices are understaffed to meet the practice’s population health needs. Additionally, the clinician workforce does not reflect the population serviced by most safety net organizations. The workforce is overwhelmingly white and monolingual English-speaking: psychologists are 88% white,[5] licensed marriage and family therapists are 79% white;[6] licensed clinical social workers somewhat more diverse at 58% white.[7]

Integrating behavioral health and primary care has been shown to increase access to services by providing BH services[8] in a lower stigma environment and addressing childcare and transportation barriers with a “one-stop shop” model. IBH research demonstrates significant improvements in patient experience,[9] health outcomes[10] and health equity.[11]

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), depression is a major contributor to mortality, morbidity, disability and economic costs in the United States. In 2021, 8.3% (21 million) of adults in the U.S. experienced at least one major depressive episode; 5.73% (14.5 million) experienced a major depressive episode with severe impairment.[12] Approximately 50% of those diagnosed with depression in the United States are also diagnosed with anxiety.[13]

Depression and other behavioral health conditions can often go undetected and unaddressed in primary care.[14] Black and Hispanic or Latino/a and, when they do, the services are of poorer quality compared to that of white patients.[15][16]

Developing, implementing and continually improving integrated care delivery within your practice is critically important; multidisciplinary, team-based care can increase equitable access to behavioral healthcare, improve patient health outcomes, enhance quality of life, and improve job satisfaction of medical providers and staff.

This guide is designed to help your practice enhance and deepen integrated behavioral healthcare and screen for and manage depression. It includes guidance on how to approach the activities of population health management in trauma-informed ways. In addition to the body of this guide, find more strategies in the resource on Trauma-Informed Population Health Management.

This guide provides practices with detailed guidance, examples, resources and tools to effectively screen for and manage depression and engage patients in integrated behavioral health services. The guide is designed to be helpful as part of an organized quality improvement strategy, with the goal of supporting substantive cultural, technological and process changes that improve population-based care and improve equitable outcomes.

The guide lists several key activities by section:

- Foundational activities: The core activities that all practices must implement to enhance integrated care delivery and engage adult patients in depression screening and treatment to achieve depression remission.

- Going deeper activities: More advanced activities that build off the foundational activities and help ensure your practice can achieve equitable improvement in depression screening and engage adolescents in depression screening and treatment.

- On the horizon activities: Additional activities focused on improving care delivery with people with severely impacting mental illness.

Sequencing activities: We recommend practices consider planning and attempting to implement the activities in the sequence provided in this guide. At the same time, we recognize that different practices may follow a different path toward prioritizing and implementing these activities. Furthermore, there is overlap between activities; many activities build off of or form the building blocks of other activities.

Testing and implementing: For each activity, we provide guidance on how to plan, test and implement the activity, along with links to other resources, technology considerations and examples. Consider testing different versions of the action steps and roles on a small scale before wide scale spread throughout your practice.

Maintaining the progress: For many activities, we have also provided tips for periodically reviewing and making improvements to key workflows even after initially implementing the change. Ongoing review and continual improvement are important for your practice to maintain your progress in population health management and to help you stay nimble in adapting to changing patient demographics, new clinical best practices, new payment policies, workforce changes and other changes at your practice.

If you implement the key activities in this guide, you should be able to achieve the following foundational competencies.

For behavioral health, your practice will be able to consistently:

- Engage patients served by your practice to validate any of your proposed process improvements and to propose alternative methods to improve quality in your focus area.

- Analyze core quality measures to identify disparities and improvement opportunities for achieving universal depression screening among all attributed adolescents and adults.

- Integrate behavioral health follow-up services as needed (e.g., for positive depression screens).

- Identify and engage behavioral health partners.

- Create a health-related social needs screening process that informs patients’ treatment plans.

- Assess current capabilities and develop a plan for ongoing improvement in data utilization, care team workflows and efficiency that includes sustainable health information technology (HIT) strategies and continuous staff training in technology.

This guide also includes sections on measurement, equity, social health and behavioral health integration and an appendix that includes helpful tools and resources. We have included information about California Medi-Cal-covered benefits and services that were up to date at the time of publishing, but benefits and billing guidance change over time. Nothing in this guide should be considered formal guidance, and anyone using this guide should check with the appropriate authorities on benefits and billing guidance.

This is a living document and will change based on continued learning on this topic and may include additional activities, examples, resources and sections in the future.

Improving the health of a population impacts everyone in a practice. Critical roles needed to engage in the work outlined in this guide and support practice change, include:

- Chief behavioral health officers (CBHOs), chief medical officers (CMOs) and other clinical leaders.

- Operation leaders, such as chief operating officers (COOs) and practice managers.

- Quality improvement leadership, like a director of quality improvement (QI), to support cultural changes.

- Coaches or practice facilitators who are partnered with teams to help identify areas for improvement and support change through change management strategies.

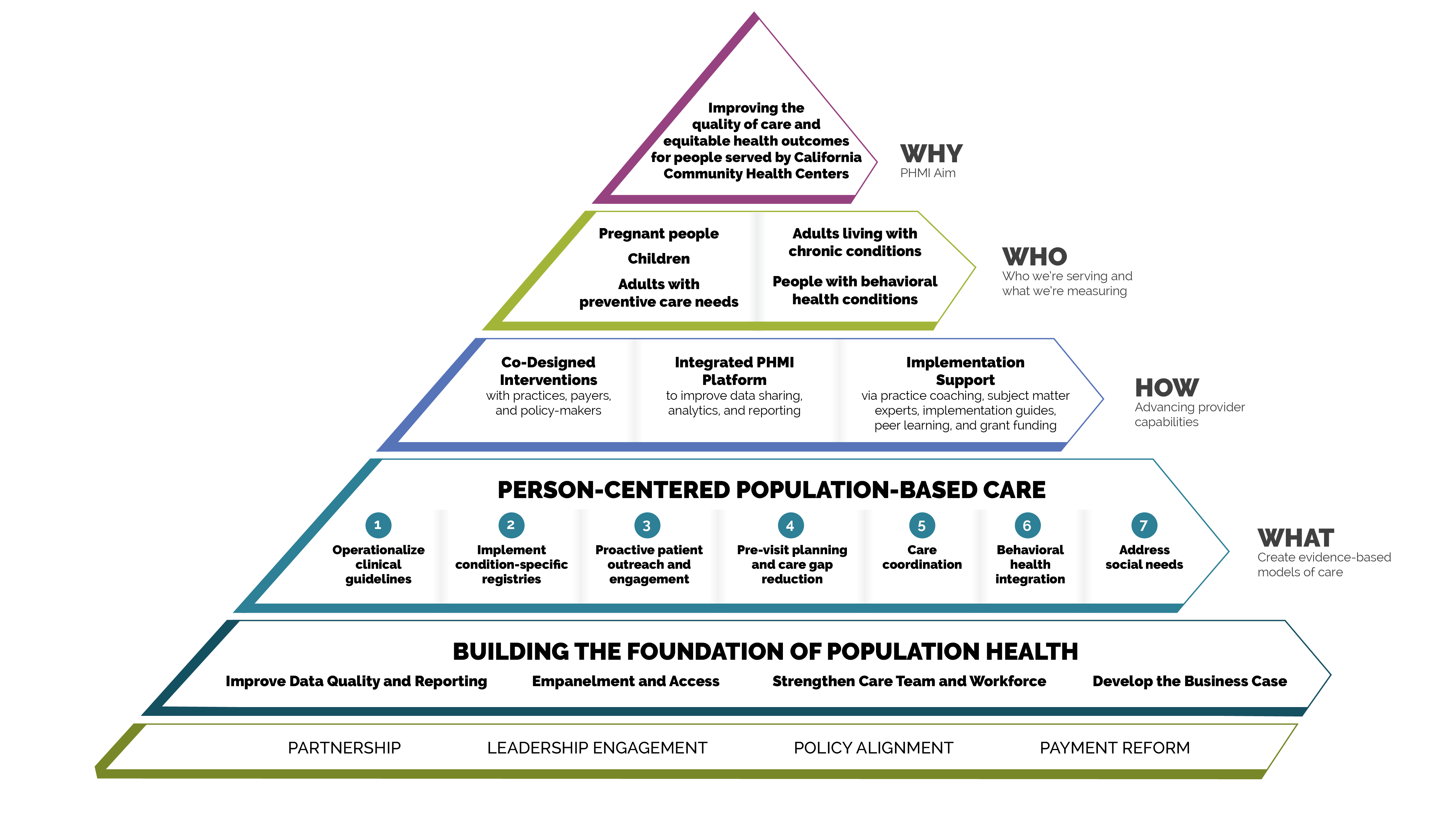

Putting the Key Activities in Context

Person-centered population-based care

Each of the key activities advance one or more of the seven person-centered population-based care change concepts:

- Operationalize clinical guidelines.

- Implement condition-specific registries.

- Proactive patient outreach and engagement.

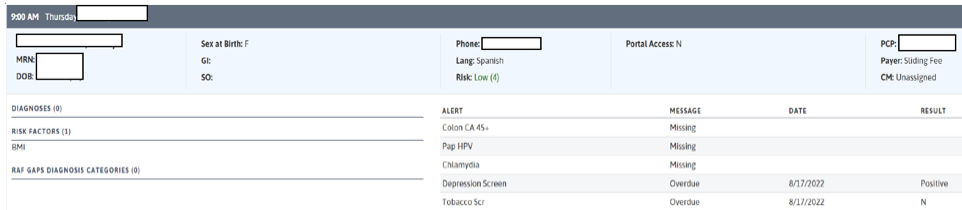

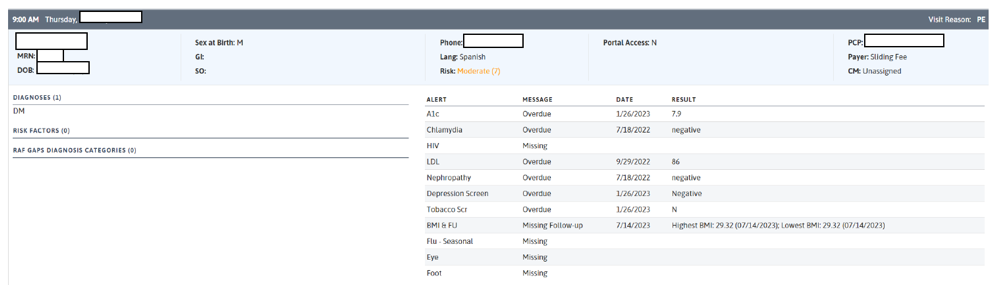

- Pre-visit planning and care gap reduction.

- Care coordination.

- Behavioral health integration.

- Address social needs.

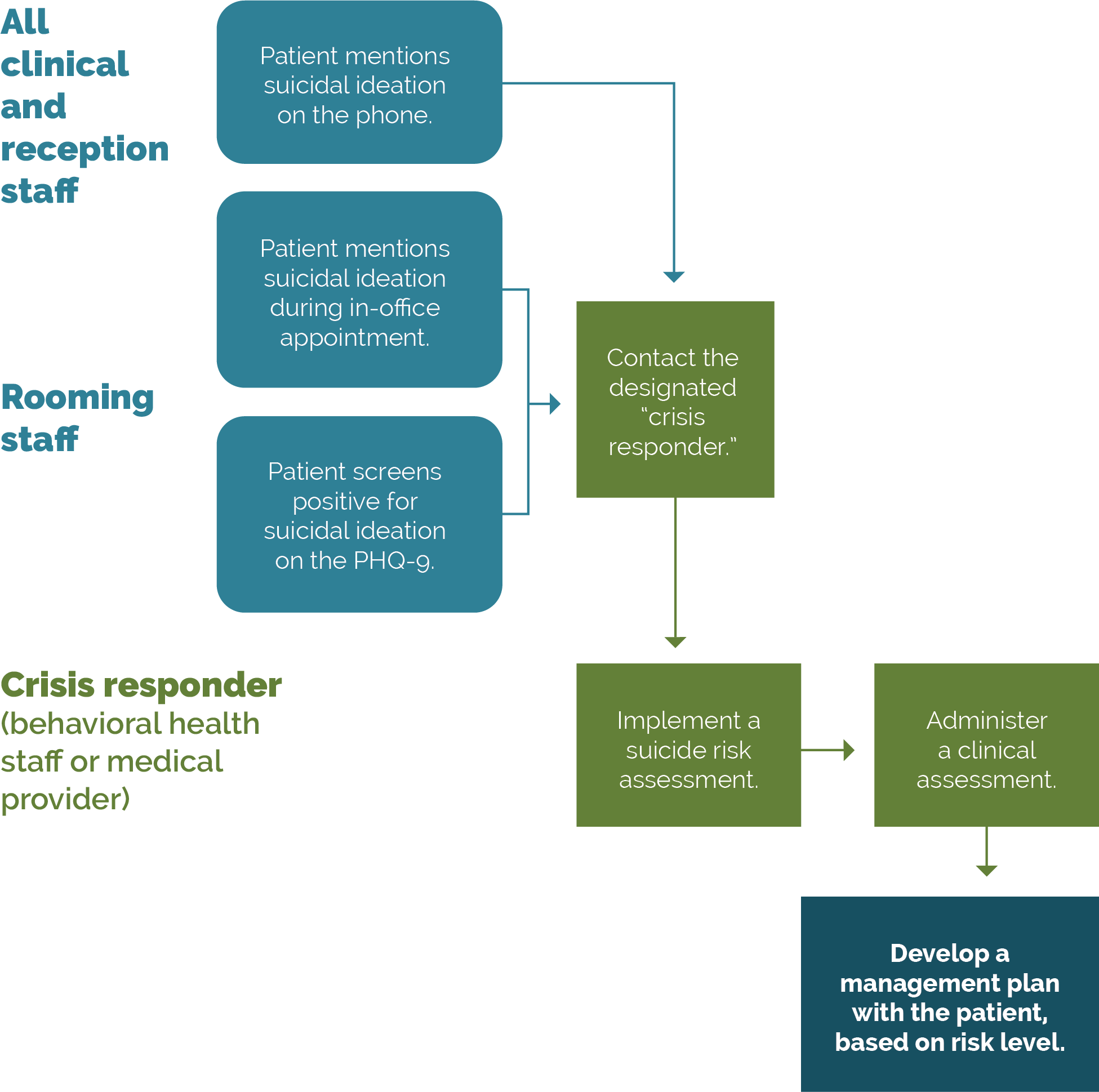

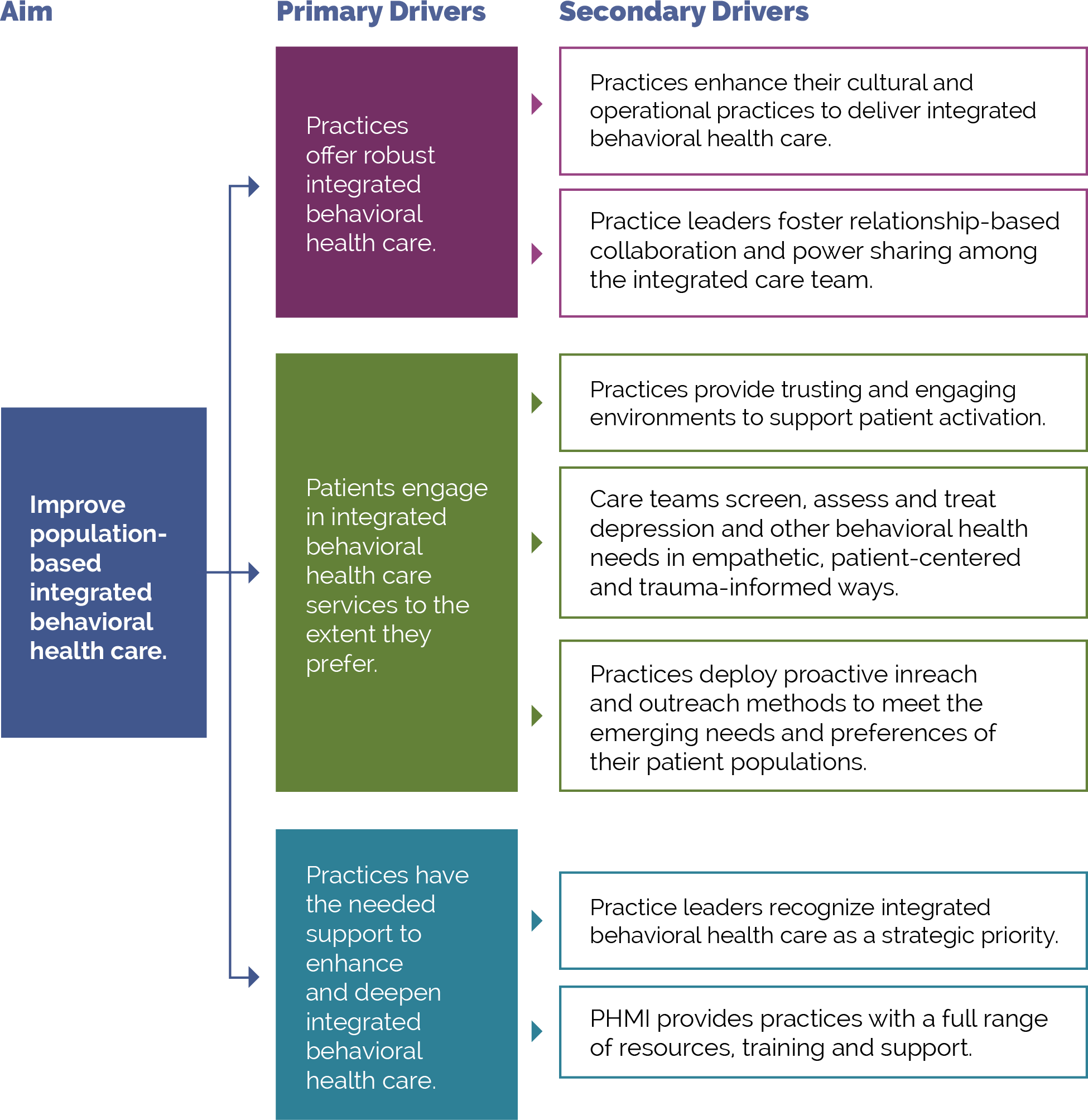

FIGURE 1: PHMI IMPLEMENTATION MODEL

The measures covered in this guide consist of Healthcare Effective Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures designated as core and supplemental measures by PHMI. These measures can be considered outcome measures because there is ample evidence that improved timely screening rates and follow-up care improves overall population health outcomes for depression. All measures use standard HEDIS definitions and are aligned with California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Ca (CalAIM) and Alternative Payment Methodology (APM 2.0). For information about these measures, reference the PHMI Data Quality and Reporting Guide

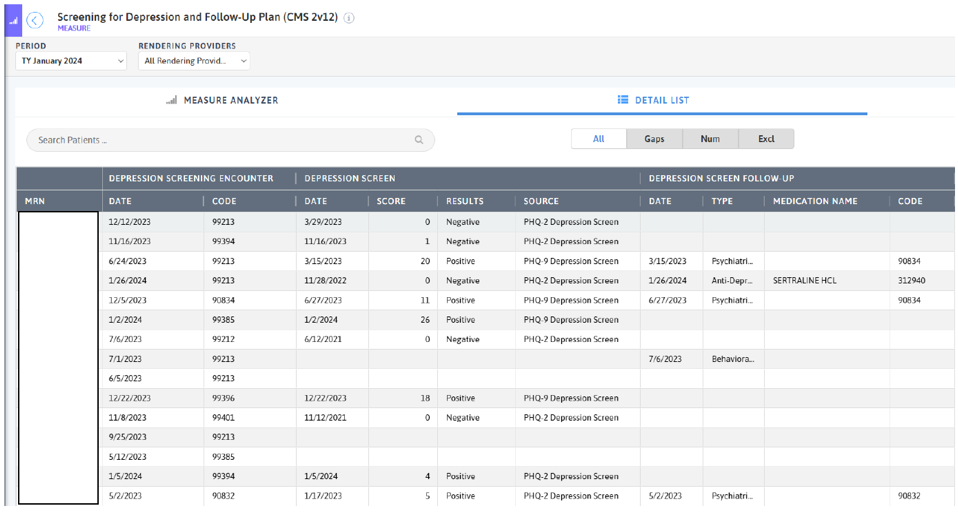

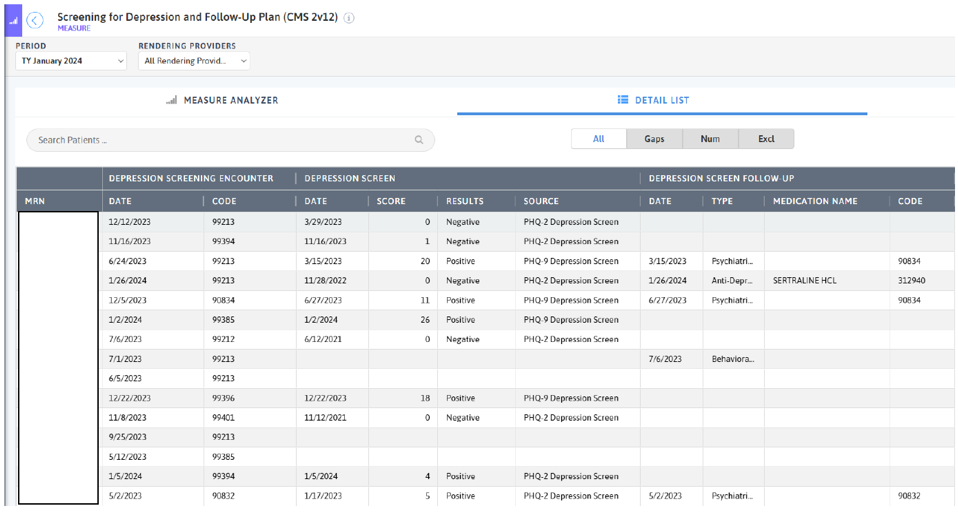

PHMI selected a few core and supplemental measures of focus for this population, though practices can track others that feel important and relevant. This guide provides detailed guidance to improve your practice’s results on the following two core and supplemental measures for people with behavioral health conditions:

- Depression Screening and Follow-Up for Adolescents and Adults (core measure).

- Depression Remission or Response for Adolescents and Adults (supplemental measure).

Core HEDIS Measures for PHMI

PHMI Population of Focus |

Measure |

|---|---|

People with Behavioral Health Conditions |

Depression Screening and Follow-Up for Adolescents and Adults Percentage of people aged 12 and older who were screened for depression using a standard screening tool and, if positive, received follow-up care within 30 days. |

Supplemental HEDIS Measures for PHMI

PHMI Population of Focus |

Measure |

|---|---|

People with Behavioral Health Conditions |

Depression Remission or Response for Adolescents and Adults Percentage of people 12 years and older with a diagnosis of depression, and an elevated PHQ-9 score who had evidence of response or remission within four to eight months of the elevated score. |

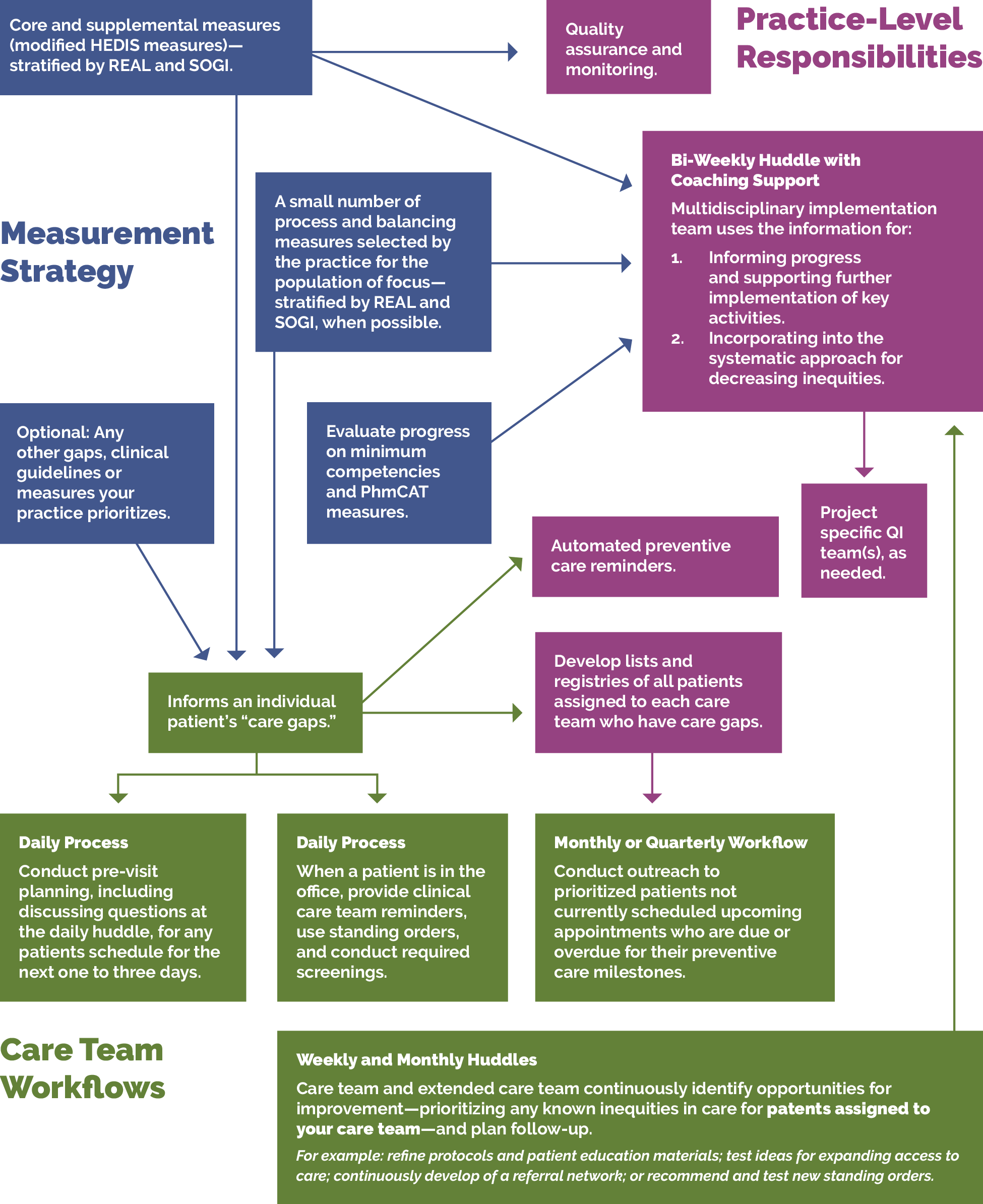

The core and supplemental measures are part of a larger measurement strategy and learning system, as outlined in Appendix A: Sample Idealized System Diagram: Weaving Your Measurement Strategy and Learning System into Practice Operations. Key Activity 1: Convene an IBH Implementation Team outlines how your practice can develop a robust measurement system to support this work. In addition to quality assurance and monitoring, measures are also used during practice operations alongside other data for learning to:

- Guide the actions of the IBH implementation team as they use a systematic approach to decreasing inequities and support implementing key activities across the practice.

- Support the care team’s efforts to advance population health and reduce care gaps through daily, weekly and monthly workflows, as well as continuous identification of opportunities for improvement.

The PHMI Clinical Guidelines Advisory Group (CGAG) was established to create a standardized approach to review, adopt and promote established clinical guidelines in the PHMI cohort. For people with behavioral health conditions, guidance includes depression screening and follow-up. For more information, see the PHMI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Key Medi-Cal Populations of Focus.

FIGURE 2: CLINICAL GUIDELINES: DEPRESSION SCREENING AND FOLLOW-UP FOR ADOLESCENTS AND ADULTS

Guideline source |

|

PHMI measure |

Depression Screening and Follow-Up for Adolescents and Adults |

Guideline language |

Complete a depression screening annually for persons 12 years of age and older. A specific screening questionnaire is not endorsed. Although USPSTF does not specify frequency, the group endorsed the recommendation to screen annually. |

Definitions |

Depression screening: A patient screened for clinical depression using a standardized assessment instrument that has been normalized and validated for the appropriate patient population (e.g., adolescents aged under 17 years or adults aged 18 years and older). Depression follow-up: A patient screened for depression with a positive result using a standard assessment instrument as above and who received follow-up care on or up to 30 days after the date of the first positive screen (31 total days). Any of the following on or up to 30 days after the first positive screen:

OR

|

FIGURE 3: DEPRESSION REMISSION OR RESPONSE FOR ADOLESCENTS AND ADULTS

Guideline Source |

Kaiser Permanente National Guideline Program (September 2023) |

PHMI Measure |

Depression Remission or Response for Adolescents and Adults (DRR) |

Guideline Language |

Measurement-Based Care

|

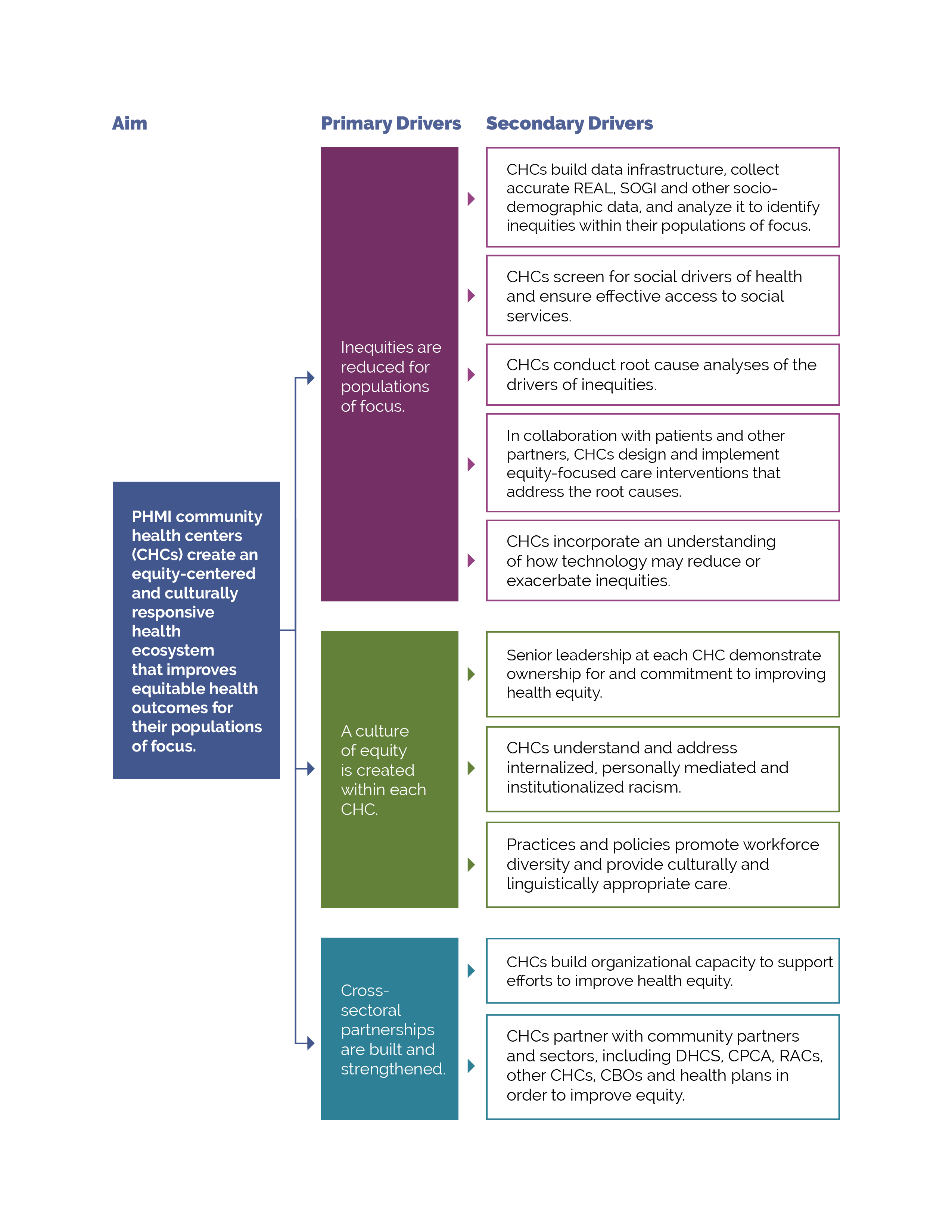

Many key activities in this guide include considerations for utilizing the intervention to improve equitable health outcomes and reduce the effects of racism, bias and discrimination. Key Activity 11: Use a Systematic Approach to Address Inequities Within the Population of Focus describes key action steps for how to make an intentional and explicit effort to identify inequities, understand root causes and reduce those inequities.

This guide also offers resources for going deeper into organizational and ecosystem-level work to advance equitable outcomes through Key Activity 18: Strengthening Community Partnerships and Key Activity 19: Strengthening a Culture of Equity. For going deeper into organizational and ecosystem-level work to advance equitable outcomes, practices can look to the PHMI Equity Framework and Approach for additional guidance.

Evidence continues to accumulate that demonstrates the many ways in which social needs impact behavioral health outcomes, so it is important for practices to consider their role in supporting their patients’ social health. For many key activities in this guide, we have highlighted considerations related to social needs at the individual level or population level, such as expanding access to integrated behavioral healthcare that meets patients where they are. A foundational activity is Key Activity 7: Use Social Needs Screening to Inform Patient Treatment Plans, which can help practices better understand and support patient- and population-level needs. Practices can help patients make connections to resources in the community to address issues such as nutrition, childcare, legal and health education needs. For Medi-Cal patients and families with high levels of social need, such as those experiencing homelessness, referrals to Enhanced Care Management and community support programs are available.

For going deeper in this area, practices can utilize Key Activity 17: Continue to Develop Referral Relationships and Pathways for common social needs and Key Activity 18: Strengthen Community Partnerships to build upon the strengths, infrastructure and resources available in the community. More information about this dual patient- and population- level approach is available in the PHMI Social Health Framework and Approach.

Foundational Key Activities

Core activities that all practices must implement to enhance integrated care delivery and engage adult patients in depression screening and treatment.

KEY ACTIVITY #1:

Convene an IBH Implementation Team

This key activity involves all seven elements of person-centered population-based care: operationalize clinical guidelines; implement condition-specific registries; proactive patient outreach and engagement; pre-visit planning and care gap reduction; care coordination; behavioral health integration; address social needs.

Overview

This activity provides guidance for developing, launching and sustaining an integrated behavioral healthcare (IBH) implementation team. This is the team within your practice that will be responsible for planning and implementing the foundational key activities in this guide and overseeing related quality improvement and equity efforts, as outlined in Appendix A: Sample Idealized System Diagram: Weaving Your Measurement Strategy and Learning System into Practice Operations. For the purposes of this guide, we will refer to it as the IBH implementation team, but your practice may decide on a different name for this team to acknowledge where you are in your integration journey, such as “integration group” or “IBH task force.”

Without a focused team, adequate senior leadership support, authority and decision-making capacity, documented goals and a timeline, IBH services often remain inadequate to improve population behavioral health. IBH services sufficient to improve population health require sustained attention and effort to integrate at the leadership, operational and clinical levels. IBH services need consistent refinement to meet the emerging behavioral health needs of patients; this requires deep commitment from an engaged, high-functioning and focused group, internal advocacy with other leaders, and creative collaboration.

This team is responsible for ensuring that all foundational key activities in this guide, including those related to screening for social needs, are implemented. When identifying potential members of this implementation team, the practice can identify a diverse group of staff who are reflective of the community served and who represent the lived experience of patients. In addition to implementing Key Activity 11: Use a Systematic Approach to Address Inequities Within the Population of Focus, the team should apply an equity lens to every step outlined in this guide to help ensure that any improvements are equitably spread among the patient population.

Relevant health information technology (HIT) capabilities to support this activity include care guidelines, registries, clinical decision support, care dashboards and reports (including social needs data), quality reports, outreach and engagement, and care management and care coordination. See Appendix D: Guidance on technological Interventions.

To enable team coordination, thought must be given to how access relevant technology and how data capture can be distributed, consistent, and integrated into workflows and how data is accessible across team members. Where possible, it is desirable to avoid duplication of data entry, siloing of information in standalone applications and databases, and the need to work in multiple applications requiring separate logins.

Action steps and roles

1. Demonstrate senior leadership ownership for and commitment to centering, implementing and refining IBH.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Chief medical officer, behavioral health leadership (e.g., BH lead, chief behavioral health officer, BH director, BH providers), clinic managers or COO.

In the context of BH integration, senior leaders are responsible for serving as high-level champions for IBH. A key role is to remove barriers of the IBH implementation team as they arise and help facilitate the change process in the organization. See Key Activity 2: Enhance the Culture of Integrated Behavioral Healthcare.

Championing IBH may include:

- Clearing the path for improvement.

- Creating and leveraging opportunities for IBH, including interpreting policy and billing landscapes.

- Devoting resources to create a BH chief and IBH implementation team.

- Protecting resources for IBH.

- Supporting and championing the vision for IBH drafted by the IBH implementation team.

There may be further foundation building work needed at your practice in order for you to succeed at some of the key activities listed in this guide. The Population Health Management Capabilities Assessment Tool (PhmCAT) is a multidomain assessment that is used to understand current population health management capabilities of primary care practices. This self-administered tool can help your practice identify opportunities and priorities for improvement. If your practice has not scored high in the domains of leadership and culture, the business case for population health management, technology and data infrastructure, or empanelment and access, consider implementing the activities listed in the four guides on Building the Foundation in parallel to working on IBH.

2. Identify leadership and key members for the IBH implementation team.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Senior leadership.

The IBH implementation team should include those empowered to make changes in workflows, policies and staff assignments. They should be respected influencers in the organization (early adopters) who can also guide the change management process. They should also include those with expertise in working with patients around behavioral health concerns.

- Appoint a champion or lead person (e.g., behavioral health integration champion) to oversee the implementation and coordination of the team.

- Identify key actors who will be the core members of the IBH implementation team. Potential members include:

- Behavioral health providers.

- Nurses.

- Panel managers.

- Clinicians.

- Social workers.

- Community health workers and other community outreach staff.

- A member of the information technology (IT) or electronic health record (EHR) team (as part of the expanded team).

- Billing manager or similar (as part of the expanded team, especially initially).

- Patient service representatives, front office staff and reception staff.

- HR personnel (as part of the expanded team).

Invite identified people to become part of the IBH implementation team and ensure that they have designated time for their participation. Lead with humility and curiosity and ensure that each team member is open to learning about the needs and strengths of people with behavioral health conditions.

3. Launch the IBH implementation team and set it up for success.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: BH lead.

This work includes:

- The first step for the IBH implementation team will be to develop a preliminary charter outlining the aims, responsibilities and timeline of this work. This includes but may not be limited to: enabling, aligning, leveraging and supporting the planning and implementation of all foundational key activities in this implementation guide so that the practice meets the foundational competencies.

- Defining roles and responsibilities, including the anticipated commitment (in hours) on a monthly basis.

- Establishing a meeting structure, file structure and communications structure to support relationship-centered, effective work.

- Dedicating time and effort to forming, storming, norming and performing as a team. The resource: Team Communication and Working Styles Template is one tool that team members can complete and share with other teammates to accelerate this process.

- Understanding baseline data related to outcomes of interest (e.g., number of positive depression screens resulting in a IBH appt or percentage of patients screened for substance use disorders (SUD) last year, etc.), along with data related to known and perceived barriers to these outcomes.

- Prioritizing elements within the scope of work, informed by baseline data and identified population needs.

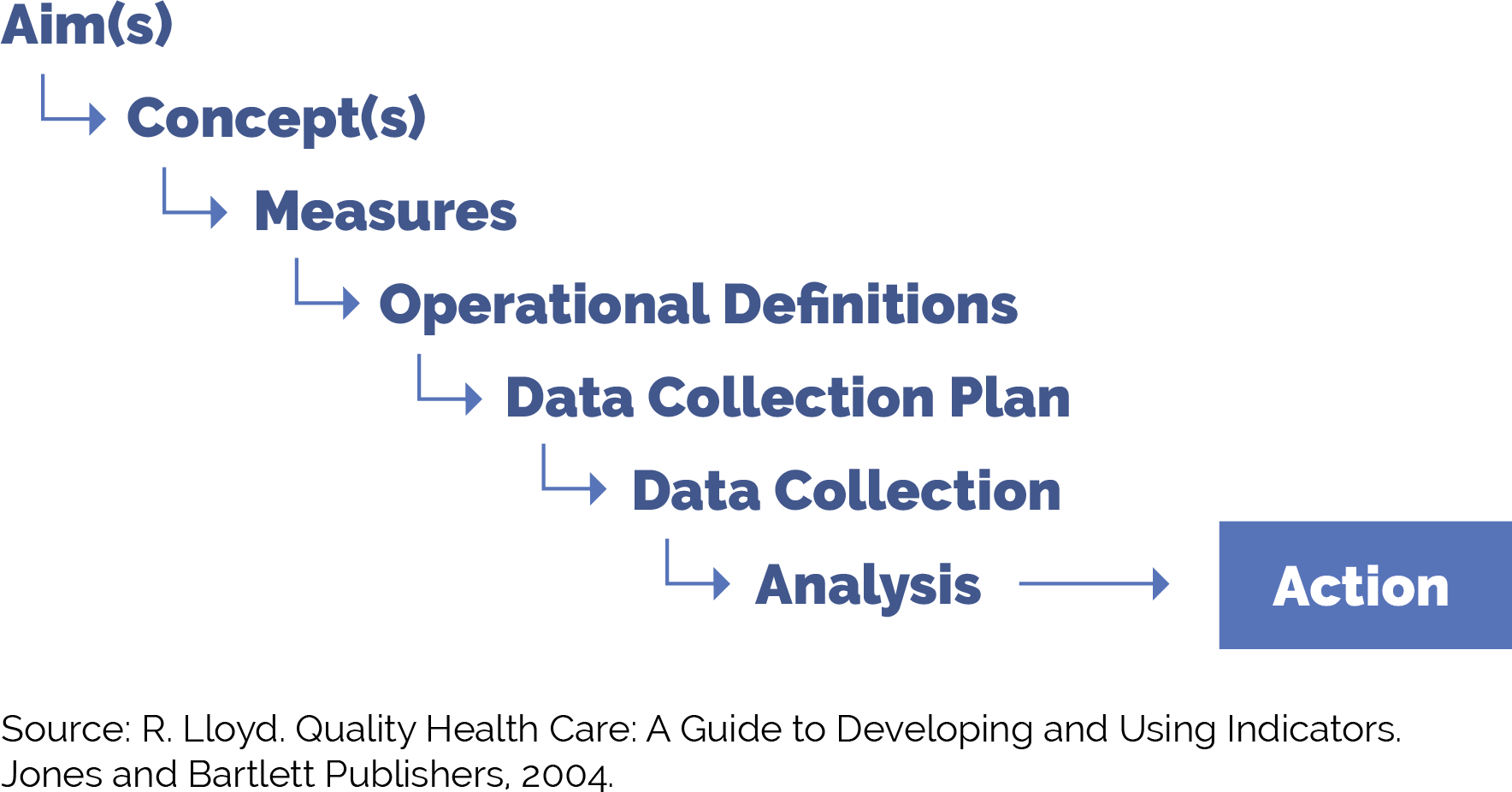

4. Develop a simple yet robust measurement strategy and learning system to guide your improvement efforts.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Panel managers with behavioral health specialist (especially initially).

A learning system enables a group of people to come together to share and learn about a particular topic, to build knowledge, and to speed up improved outcomes. A simple yet robust measurement strategy and learning system:

- Contains a balanced set of measures looking at outcomes, processes and possibly unintended secondary effects (e.g., increased cycle time and impact on team well-being).

- Incorporates the patient perspective and the perspective of staff (front desk and others), care team members and management.

- Allows the team to determine if the process or system has improved, stayed the same or worsened.

- Helps guide improvement efforts and informs practice operations. See Appendix A: Sample Idealized System Diagram: Weaving Your Measurement Strategy and Learning System into Practice Operations for a sample system diagram for how your measurement strategy can be used to support practice operations.

Your practice should track the core and supplemental measures for depression screening, follow-up and remission. These can be considered outcome measures because there is ample evidence that improved timely screening and monitoring will improve overall population health outcomes for behavioral health needs.

In addition to the core and supplemental measures, practices should track process measures and balancing measures. Appendix C: Developing a Robust Measurement Strategy describes and defines the key milestones in the development of a robust measurement strategy, including definitions for each of these terms.

Suggested process measures:

- Percent of 12-and-over patients who had a depression screen in the last 12 months.

- Percent of positive screening results in the reporting month that have documentation of follow up.

- Note on tracking these process measures: The PHQ-2 will meet the expectation of screening, with the expectation that positive PHQ-2 screens lead to PHQ-9 administration. The administration of PHQ-9 as a screen will also meet the expectation.

Suggested balancing measures:

- Number of patients who screened positive on anxiety, depression, adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) or SUD screening and who were referred to IBH.

- Number of patients who were referred and who saw BH within two weeks.

- One or more measures related to patient satisfaction.

- One or more measures related to staff satisfaction.

Practices can also look at other metrics to understand the progress of specific improvement initiatives over time. This may include:

- Progress on the Population Health Management Capabilities Assessment Tool (PhmCAT).

- Progress towards foundational competencies listed in this implementation guide. For example, “Yes or No: Did your practice achieve the following foundational competency ‘Analyze core quality measures to identify disparities and improvement opportunities for achieving universal depression screening among all attributed adolescents and adults’?”

- Any other care gaps, clinical guidelines or measures your practice feels are important to prioritize.

Applying an equity lens

To correct pervasive health inequities for people of color and other populations who experience historical marginalization, practices can stratify their data based on race, ethnicity and language (REAL), sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI), and other patient characteristics (e.g., social needs, etc.), reflect on the data, and consider specific strategies to address them. Key Activity 11: Use a Systematic Approach Address Inequities within the Population of Focus provides a brief overview of known inequities for mental healthcare and how to begin to address them.

Putting it all together

We recommend that your practice records your measurement strategy in one place. This resource: Measurement Strategy Tracker contains all the fields we believe are most useful, and it can be customized to meet your practice’s needs.

5. Plan and hold regularly scheduled meetings of the IBH implementation team to make adjustments based on data from the team’s measurement strategy and feedback loops.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: IBH implementation team lead or clinical coordinator or other individual tasked with coordinating the work of the team.

- Hold time on team members' calendars for standing meetings. Consider meeting twice monthly to start with. The frequency, duration and focus of these meetings may change as you consider additional populations or subpopulations and additional sites or locations and as the nature of the work changes.

- Develop a system to efficiently report on all work streams and track follow-up items. The resource: Action Plan Template is one tool that can be used to focus your team around the foundational competencies and define responsibility for action steps to be taken for each project your team has prioritized to work on.

- Review data and feedback at least monthly to celebrate team successes and adapt efforts as needed. Adaptation could include any or all of the following:

- Amending the charter.

- Modifying meetings or meeting structures.

- Changing the team composition (e.g., adding or removing members).

- Refining key activities to better meet the needs of patients and staff, improve outcomes, or reduce inequities.

- Modifying the measurement strategy and/or feedback loops to better understand what is and isn’t happening.

- On an annual basis, the team’s charter and core membership should be reviewed. As the goals of the IBH implementation team are met, the team could disband, meet less frequently (e.g., twice per year), or fold this meeting into a similar standing meeting that occurs separately.

Resources

Health Center Quality Measurement Systems Toolkit

Health Alliance of Northern California created a summary crosswalk of measurement sets, which provides an overview of alignment between measurement systems. It includes in-depth information on each Uniform Data System (UDS) or Quality Incentive Pool (QIP) clinical measure for depression screening and depression remission, which are contained in a spreadsheet. The document also shares suggested clinical interventions and community interventions for depression screening and appropriate follow-up in rural northern California.

KEY ACTIVITY #2:

Enhance the Culture of Integrated Behavioral Healthcare

This key activity involves the following elements of person-centered population-based care: behavioral health integration.

Overview

Promoting a culture of integrated care delivery begins by establishing a clear vision of whole-person care and its implications, ensuring that all clinic staff understand their respective roles in supporting care of the whole person, and addressing the physical, social and behavioral needs of the clinic’s patient population. Although there are a number of models and strategies of IBH for which an evidence base has been developed, there is no single model that is a fit for every organization. Practices should not let their concept of an ideal model get in the way of implementing something that works within their own setting. It’s important for the practice to be continually moving toward an integrated whole-health system with both primary care and behavioral health services. Most organizations continually evolve integrated care services over time, modifying their integration strategies as they gain experience or the availability of resources changes.

Integration of behavioral health and primary care is still relatively new, starting in the early 2000s. Developing integrated care is not as straightforward as simply hiring a behavioral health provider to the practice. It is an ongoing process of culture change and transforming care delivery to support whole-person care. Integration requires more than clinical integration; it requires integration of behavioral health leaders into senior or executive leadership, integration of operational processes related to behavioral health, and intentional power sharing among the care team with purposeful design of workflows. These efforts collectively contribute to an enhanced organizational culture that incorporates the perspectives of multiple professions working together to support patients and families in their care.

Working as a multidisciplinary team in an integrated way provides opportunities for the team to understand a wide range of drivers for health outcomes. Ideally, integration helps the care team make care recommendations that better accommodate patient experience and engage more meaningfully with the interconnectedness between physical health, emotional health and social needs.

IBH enables the care team to tend to whole-person care, making every effort to desilo interventions and interactions with patients. This approach enables essential screening and monitoring of behavioral health needs and the delivery of comprehensive care, with care coordination and collaboration among an integrated care team. For example, a behavioral health specialist reviews the pre-visit plan, notes that the patient is due for diabetes screening, provides grief counseling and offers to link the patient to the medical assistant who then uses a standing order to provide necessary screens (e.g., foot check, etc.). Benefits of integrated behavioral health extend beyond the patient to care team members, as well. Professionals working in integrated settings report increased skills and greater satisfaction with their work as they feel better able to meaningfully respond to patient needs.

IBH services will vary considerably in capacity between practices. Practices in more rural areas typically have much larger IBH departments with significant BH case management and psychiatry resources, while those in urban areas often have smaller IBH departments and nascent case management and psychiatry. This is typically due to the differences in BH resources in the surrounding community; when communities have insufficient BH resources and county systems are constricted, rural practices often build departments to meet all or most of their patient’s BH needs. When communities are rich with BH resources, urban practices often rely more on outside referrals for BH care. In this way, each practice’s IBH vision will be informed by community BH resources as well as the patient population’s needs.

Integrated behavioral health enables patients to gain support in the primary care setting, expanding access to care for groups underserved by community-based behavioral health care. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)’s integration academy provides further discussion of the role of behavioral health integration in reducing inequities by reducing fragmentation, stigma, and healthcare utilization and quality of care and health outcomes, especially for people with depression, anxiety, diabetes, high cholesterol and high blood pressure.

Integrated care allows a team to take a whole-person care approach and begin to understand more fully the root causes of poor health outcomes, potentially leading to improved outcomes in the patient population. Unmet social needs are often a contributor to various behavioral health conditions (see Key Activity 10: Develop a Social Needs Screening Process that Informs Patient Treatment Plans). A culture of integrated healthcare enables the care team to identify unmet needs and help patients connect to community resources. Furthermore, patients who might be hesitant to endorse needs on a social needs screening form may be more likely to disclose these needs in a session with care team members who come off as empathic and nonjudgmental, prompting referrals and connections. Integration of behavioral health screening and counseling, coupled with screening for social needs, can lead to a comprehensive care plan that aligns care to support individuals’ holistic needs and build on their strengths.

Relevant health information technology (HIT) capabilities to support this activity include pre-visit planning tools; care guidelines; registries; clinical decision support; care dashboards and reports, including behavioral health screenings and social needs data; quality reports; outreach and engagement; and care management and care coordination. See Appendix D: Guidance on Technological Interventions.

To enable team coordination, thought must be given to how access relevant technology and how data capture can be distributed, consistent and integrated into workflows and how data is accessible across team members. Where possible, it is desirable to avoid duplication of data entry, siloing of information in standalone applications and databases, and the need to work in multiple applications requiring separate login.

Action steps and roles

1. Co-create a shared updated vision for IBH in the practice.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: IBH implementation team with senior leaders.

This is an opportunity to evaluate current IBH services, both strengths and shortcomings, and collaborate to establish a shared vision, aims, and strategies for enhanced integrated care. Because integrated behavioral health often means different things to different team members and leaders, this is also a time to align understanding about goals and strategies.

One technique for creating a shared vision is to use patient Journeymapping.[17] It can be especially illuminating to map both examples of current patient journeys through each step of obtaining primary care and behavioral health services as well as the ideal patient journey. Mapping ideal patient journeys can facilitate a shared vision for integrated care, with patient preferences, experiences and outcomes as the north star.

2. Align integrated care strategies to the strengths and needs of the population.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: IBH implementation team with senior leaders.

Practices have an array of information to review to learn about population needs, including screening results, community or secondary data sources, care team experiences, and patient experience data. Dedicate care team meeting time to reviewing the needs of the population served and current capacity to provide care.

- Using EHR reports to identify the number of patients with prescribed psychotropic medications can provide a population-level view of a subset of patients with behavioral health conditions in the practice.

- Review aggregate universal screening data to better understand the behavioral health needs of the population. See Key Activity 7: Use Care Gap Reports or Registries to Identify All Patients Eligible and Due for Behavioral Health Screening and Follow-Up for guidance around leveraging the EHR to understand which patients are due or overdue for screening. More about screening for depression, anxiety, unhealthy substance use, and adverse childhood experiences is detailed later in this guide.

- Review EHR reports for current population outcome data and develop improvement aims. See Key Activity 11: Use a Systematic Approach to Address Inequities within the Population of Focus for more about ensuring an equity lens on your review data and selection of improvement aims.

- An evolving view into strengths and needs of people in the population can emerge through the repeated administration of the Three Part Data Review.[18] Consider deploying a care team member with enhanced listening skills to learn from five to 10 patients per quarter. At the same interval, query care team members and review quantitative data, then leverage an existing meeting to assemble the learning from the three-art data review, identify themes, surface opportunities for improvement, and plan tests of change.

- Calculate the current capacity for providing behavioral health services and the established level of need. Develop short- and long-term population health goals; for most practices, it is unlikely there is currently enough capacity to meet the practice population’s behavioral health needs. See Key Activity 4: Develop Strategies to Maximize Capacity of IBH Services for more information.

3. Confirm a set of IBH strategies that aligns with the organization’s aims, the population’s strengths and needs, and organizational capacity.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: IBH implementation team with senior leaders.

Assess the existing state of behavioral health integration within the clinic to define the organization’s current strategies for IBH while keeping the overarching vision as a north star.

Integrating behavioral health into your practice may involve an embedded behavioral health specialist on the care team, co-location of services working with a behavioral health partner, a telehealth model, or a blended approach.

Define a set of strategies to meet the specific needs and build on the strengths of the patient population, and then develop workflows for behavioral health conditions to guide the care team in defining their roles. Collaboratively designing strategies and workflows with patients is an impactful way of ensuring relevance of interventions and strengthening partnerships with patients; the practice’s consumer advisory board is a natural fit for this. Codifying workflows and using them to guide staff and onboard new team members supports standardized care delivery and fosters team members’ growing comfort in addressing behavioral health and social needs.

Examples of aims and strategies of the updated IBH vision might be:

- Increasing the ratio of behavioral health clinicians to one to every two primary care providers.

- Incorporating a behavioral healthcare manager or BH care coordinator on each care team.

- Ensuring primary care providers (PCPs) are competent, comfortable and willing to manage medications for depression, anxiety and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

- Increasing operational integration.

- Training all SUD providers to do mental health counseling.

- Integrating psychiatric specialists into the practice.

- Developing a feasible model for warm handoffs, using interns or community health workers (CHWs).

4. Develop relationship-based collaboration among the multidisciplinary care team.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: IBH providers or leaders, outside trainers.

IBH requires a practice to assess the skills and capacities your team has and make reasonable efforts to align needed support with the needs and strengths of your patients. When the IBH care team is assembled, the ongoing work of cultivating relationships among care team members begins. Leadership must establish expectations that care team members will identify their own skills and learn about those of their colleagues, learning about each other’s roles with patients and families and among the care team. Leadership will support the team to acknowledge and have the resources to spend the time and effort required to develop trust among the care team and continuously attend to the development of a shared language. Conduct regular check-ins to reinforce shared language and update the shared language based on emerging research and best practices. Develop and support staff capacity to recognize and manage their own trauma histories that they bring into patient care.

Build opportunities to develop a shared understanding among the care team. Staff training is a great opportunity to leverage reflection time and highlight staff members’ strengths and learning potential (e.g., identify roles who could provide screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment (SBIRT) interventions at the time of the visit). Train all staff in trauma-informed care and early identification. Assess staff understanding of health equity, health literacy and cultural humility; implement training programs to address gaps. For connection to social needs resources, train staff (e.g. front desk staff, medical assistants, behavior health specialist, etc.) on available community resources.

For more on this topic, see Key Activity 12A: Fostering Collaborative Teamwork with a Focus on Power Sharing Among Disciplines.

5. Universally train all relevant employees in administering and responding to sensitive screenings.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: IBH providers or leaders, outside trainers.

Screenings are only effective when patients feel comfortable with self-disclosure. People with substance use disorders, adverse childhood experiences, and other mental health conditions are often understandably hesitant to endorse symptoms in screening, given that behavioral health conditions are historically stigmatized and many patients who have disclosed these conditions may have experienced judgment in healthcare settings.

- Training in empathic, nonjudgmental communication for staff and providers facilitates a trusting relationship and increases the likelihood patients will honestly share what they are struggling with during the screening process. Specific training is necessary on a range of topics, including patient self-administered and staff-administered screenings, how to introduce screening tools, evidence-based trust-enhancing communication strategies, and how to skillfully respond to endorsements. The following resources provide examples and guidance on framing, administering and responding to screenings.

- Chapter 4 of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)’s TIP 57: Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Service provides detailed guidance on trauma-informed screening and assessment.

- Resources from EM Consulting:

- Chapter 3 of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)’s Guide to Using the Accountable Health Communities Health-Related Social Needs Screening Tool provides promising practices for universal social needs screening that is also relevant for other sensitive screenings.

6. Establish parity of behavioral health and medical departments.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: CEO, CMO, CBHO, board.

Transforming the care delivery system to address whole-person health and improve population well-being requires integration of behavioral health leadership at the executive level. Elevating BH leadership to chief behavioral health officers (CBHOs) with parity to chief medical officers (CMOs) and a seat at the executive leadership table is fundamental to creating true integrated care systems.

Implementation tips

See Key Activity 3: Enhance Operational Integration of Behavioral Health for other tips and resources that will support operational integration.

Resources

KEY ACTIVITY #3:

Enhance Operational Integration of Behavioral Health

This key activity involves the following elements of person-centered population-based care: behavioral health integration.

Overview

Integrated care delivery needs a foundation of integrated operations, including practice management, scheduling appointments, teamwide access to patient data in the EHR, integrated consent forms, and more.

Integrated operations support the integration of care delivery with team access to departmental data and administrative support. A purposeful intent to integrate practice operations will avoid the pitfalls of separate, duplicative or insufficient operational infrastructures. Without sufficient operational integration, administrative and operational tasks often fall on BH clinicians, taking away from clinical time and potentially contributing to burnout, while clumsy integration may be experienced as disruptive or distracting by the care team and patients alike. Operational integration builds on the strengths and structure of existing operational resources, protocols, policies, workflows and practices.

Practices can mitigate individual case-by-case decisions, which leave more room for bias by integrating behavioral health operations and administration with existing structures, protocols, policies, workflows, support structures, and standardized decision-making. Without integrated operations, administrative and operational tasks can become unacknowledged and unpaid labor, often performed by lower wage staff.

When IBH is integrated operationally, building out social needs screening and response processes is straightforward and efficient. Many of the strategies listed in this section are applicable to integrating social needs care, such as integrated consents to treat.

Relevant health information technology (HIT) capabilities to support this activity include pre-visit planning tools; EHR documentation tools (e.g., templates and screeners); care guidelines; registries; care dashboards and reports, including behavioral health screenings and social needs data; quality reports; outreach; and care management and care coordination data. Tools needed for business intelligence include productivity and access data. See Appendix D: Guidance on Technological Interventions.

To enable team coordination, thought must be given to how to access relevant technology, how data capture can be distributed, consistent, and integrated into workflows, and how data is accessible across team members. Where possible, it is desirable to address the issue of siloing information in standalone applications with a goal of increased sharing of clinical diagnoses across the organization (e.g., BH and medical).

Action steps and roles

Suggested team member(s) responsible: CBHO, CMO, COO or clinic director, IT lead, QI lead.

Examples of operational integration methods include:

- Develop integrated forms: Implement a single consent to treat form and a single release of information form, both of which include all services offered at the organization. Given the differing legal and regulatory expectations between medical and behavioral health professions, this exercise requires modifications to existing forms, legal review, and retraining staff in information sharing practices. Example forms are provided in the resources section below.

- Integrate the electronic health record: Behavioral health providers must be considered full providers in the EHR system and be able to chart in an integrated health record with minimal firewalls or separate confidential tabs. BH diagnosis should populate within a shared problem or diagnosis list. Organizations should also have a behavioral health EHR trainer to support behavioral health providers.

- Integrate policies and procedures: All policies and procedures become integrated, addressing both medical and behavioral health. For example, procedures for urgent psychiatric situations can be added to those for urgent medical situations. Similarly, behavioral health protocols can be added to protocols for triage, referrals, and call center guidance scripts. New policies may need to be created, such as an integrated records policy and a policy to guide decisions on seeing employees as patients.

- Integrate administrative support: All administrative support provided to medical providers and teams is provided to behavioral health providers, typically proportional to the number of patient visits. This includes receptionist and call center support for scheduling or rescheduling; integration of behavioral health services into the organization's appointment reminder system and missed appointment follow-up system; proportionally equal access to language interpretation and translation services; support for copying, filing, filling out forms, and sending letters to and for patients; and equal assistance for referrals from the organization’s referral clerks or center.

- Represent behavioral health services in community-facing products: Behavioral health services are on the organization's website, printed marketing materials, community reports, posters, and other community-facing products. Behavioral health is also represented at community outreach events, such as health fairs. Within the organization, behavioral health providers are identified the same way medical providers are. For example, if medical providers have their names on the door or wall of the site and have business cards in the reception area, behavioral health providers have the same.

- Ensure parity of behavioral health treatment supplies: Behavioral health providers have a standard ordering process for their treatment supplies, just as medical providers have a standard ordering process for their equipment. The importance of supplies such as appropriate furniture and alternative lighting, as well as games for child patients or specific books for patients, are treated as equivalent to stethoscopes or exam tables for medical providers.

- Ensure QI and IT operational support for IBH: Just as it is done for the medical department, regular reports on productivity, cost, revenue and QI are run specifically for the IBH department.

- Support recruitment and retention: The organization’s human resources (HR) department provides support in developing job descriptions, recruitment postings, candidate selection, and hiring and retention. HR should have a behavioral health-informed hiring and selection process that is tailored to the specifics of practicing in an integrated setting.

Resources

AHRQ Integration Academy Playbook

Web-based comprehensive guide from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) on behavioral health and primary care integration. Resources range from planning for integration, including creating a vision, preparing the infrastructure in your setting, and establishing protocols and clinical workflows to manage and treat your patients. The self-assessment checklist takes about 10 minutes and can be completed by members of the IBH team before, during or after implementation of integration strategies to assess the practice’s progress on integration.

KEY ACTIVITY #4:

Develop Strategies to Maximize Capacity of IBH Services

This key activity involves all seven elements of person-centered population-based care: behavioral health integration.

Overview

This key activity involves conducting a gap analysis to determine the scope of needed behavioral health support and developing strategies to provide such support. Strategies may include training medical assistants and CHWs to provide behavioral health support, enhancing medical providers’ skills to identify and support behavioral health needs, and recruiting a range of behavioral health support functions.

Like much of the nation’s healthcare delivery system, there is a severe shortage of BH providers in California. A report published by the University of California, San Francisco in 2018 – even before the pandemic sent need skyrocketing – predicted that, by 2028, demand for behavioral health clinicians will be 40% more than supply. This shortage is a significant barrier to sufficient staffing of IBH departments across California’s practices. The overwhelming majority of Community Health Centers (CHCs) are deeply understaffed to meet the behavioral health needs of the community served. Research consistently shows that 70% of primary care visits are psychosocial-related,[19] and over 40% of primary care patients want and need behavioral health services.[20]

Chronic disease management is enhanced by attending to behavioral health needs, as patients are better able to engage in chronic disease management activities, including the behavior change that is required to manage their chronic conditions, when their behavioral health needs are met. Additionally, patients are more likely to feel connected to and supported by the practice when their BH needs are met, potentially increasing the kept appointment rate.

At the same time, working in integrated ways offers team members the camaraderie and support of sharing and shouldering the work together, supporting staff retention. On a practical level, each member of the integrated care team learns new skills in the process of working in integrated ways together.

People of color and non-English-speaking patients have worse access to behavioral health services in comparison to white English-speaking patients. Expanding the capacity of behavioral health services, with a focus on BH providers who are culturally and linguistically concordant with the population served, is fundamental to equitable health outcomes.

Relevant health information technology (HIT) capabilities to support this activity include patient registries, care guidelines, quality reports, outreach, care management and care coordination data, and patient surveys. Tools needed for business intelligence include patient population-level data (e.g., total patients served, including REAL data, managed care plan (MCP) attribution), provider productivity (particularly behavioral health), and access data.

Action steps and roles

As most organizations have some level of IBH services, it may be helpful for the leadership team, including BH leaders, to complete an IBH organizational depth- assessment. A baseline assessment of behavioral health capacity can help in developing a plan for future broadening and deepening of BH services.

1. Conduct a gap analysis to determine the number of BH providers necessary to meet the patient population's needs.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: IBH implementation team.

A simple gap analysis formula is based on research that consistently shows 70% of primary care visits are psychosocial-related[21] and over 40% of primary care patients want and/or need behavioral health services.[22] However, not all patients with behavioral health conditions will be best served by the practice. Estimating the number of patients with behavioral health needs that may be appropriate for care from county behavioral health systems or another system of care is important in developing an accurate estimate of the number of patients who are most likely to obtain BH care within the practice. This calculation will vary between organizations, as each practice is unique, as are the surrounding communities. Some communities will have more resources to care for people with BH conditions, in which case a practice may refer out a higher percentage of patients. Many practices, however, are in communities with few resources for BH care; practices may be the primary or only provider for BH care in the region. In this case, calculating a gap analysis would include a higher number of patients with BH needs being cared for within the practice.

By taking into account the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) behavioral health providers and the number of patients an average behavioral health provider sees per month, organizations can estimate a rough number of the behavioral health providers required to meet the practice’s patient population needs.

Most practices will fall within the range of needing one behavioral health provider per 1,000 to 3,000 patients or one behavioral health provider per one to two primary care providers (PCPs typically have panels of about 1,400 patients). The PHMI Care Teams and Workforce Guide emphasizes this ideal ratio (see Figure 3 for ideal ratios and Figure 4 for recommended licensure):

- One BH specialist, such as a licensed clinical social worker (LCSW) or licensed marriage and family therapist (LMFT) to every two PCP panels to provide day-to-day support both for the care team and patients with behavioral health needs. Currently in California, LMFT services are considered part of the prospective payment system (PPS) rate. While most health centers seek to hire a BH specialist for whom they can bill separately, there are some teams that hire an LMFT to provide brief targeted interventions and support holistic patient care. This staffing model for integrated BH provides a more indirect return on investment through its potential positive impacts on primary care provider retention.

- One consulting BH provider (e.g., clinical psychologist or other psychiatric prescriber) for every 10 PCP panels to provide pharmacological treatments or extensive psychological testing.

The ratio is meant to give practices a framework and goal for developing behavioral health as a core service line over time. The necessary staffing ratio will be clarified through continuous monitoring of emerging patient needs and maintaining current and evolving knowledge of community resources. As care team members, such as primary care providers and nurses are increasingly confident in their ability to assess and respond to patient health behavior changes, behavioral health resources will increasingly be leveraged for care delivery focused on patients with behavioral health conditions that require a higher level of care.

FIGURE 3: RECOMMENDED RATIOS AND RESPONSIBILITIES FOR SELECT CORE CARE TEAM AND EXPANDED CARE TEAM MEMBER TO SUPPORT BEHAVIORAL HEALTH INTEGRATION

Collaborating Care Team Member |

Primary Responsibilities |

Recommended Ratio* |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

CORE CARE TEAM |

||||

Day-to-Day; Organized, Evidence-Based Care |

||||

Primary Care Provider (PCP) |

Provides direct patient care, including diagnoses and treatment. |

One FTE per panel |

||

Medical Assistant (MA) |

Assists the PCP with direct patient care and is responsible for patient flow on the day of a visit, including pre-visit planning and visit/room preparation. |

One FTE per panel |

||

Social Health Support/Community Health Worker (CW) |

Helps identify and connect patients to social health services. |

0.5 FTE per panel |

||

Behavioral Health Specialist |

Provides day-to-day support for care team and patients with behavioral health needs. |

0.5 FTE per panel |

||

EXPANDED CARE TEAM |

||||

Behavioral Health Integration |

||||

Behavioral Health Consultants |

Clinical psychologist and psychiatrist provide additional behavioral health services through psychological evaluation, substance use disorder diagnosis and treatment, and prescribing medications. |

One FTE shared across approximately 10 panels |

||

Medication Management |

||||

Clinical Pharmacist |

Medication management and patient/provider medication education. |

One FTE shared across approximately 10 panels |

||

FIGURE 4: CARE TEAM DUTIES AND RECOMMENDED LICENSURE FOR BEHAVIORAL HEALTH INTEGRATION

Care Team Role |

Expanded Duties |

Recommended Education/Licensure |

|---|---|---|

|

||

|

Behavioral Health Specialists: Licensed Social Worker (LCSW) Marriage and Family Therapist (MFT) |

|

As per state licensure. |

|

Consulting Behavioral Health Providers: Clinical Psychologist |

|

As per state licensure. |

|

Psychiatrist or Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioner (PMHNP) |

|

MD with specialty training in psychiatry. NP with specialty training in psychiatry. |

|

Clinical Pharmacist |

Note: See Care Teams Resource 1 for additional information. |

Doctor of Pharmacy degree. Many have completed post-graduate training. |

2. Identify core strategies to increase BH provider capacity.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: IBH Implementation team.

Most practices are not at the ratio of BH providers necessary to meet the needs of the practice’s population. Below are options for increasing capacity to provide integrated behavioral healthcare.

- Expand the scope of care team members to provide mental health counseling.

- Motivational interviewing, cognitive behavioral interventions, behavioral activation, psychoeducation, skillful listening, and supportive counseling are all evidenced-based treatments for behavioral health conditions. Licensure is not legally or ethically necessary to engage in these interventions. Grouped together, these interventions can be referred to as behavioral health counseling, behavioral health coaching, or other names that fit within your practice’s conventions.

- Training selected CHWs, case managers, SUD counselors, and care coordinators in the interventions above can significantly increase access to IBH services. Providing clinical supervision, support, and continued learning from licensed clinicians ensures continual growth and safety. Mental health counselors without traditional licenses or degrees have been shown to have to have outcomes comparable to licensed clinicians and are widely used in lower-income countries as a solution to clinician scarcity.[23]

- In addition to addressing access, this strategy addresses the need for more linguistic and cultural concordance in the BH workforce with the community served.

- Two training providers that offer programs to build capacity of frontline staff include The Lay Counselor Academy, Harvard University’s EMPOWER initiative, and CETA Global. Note these offerings may have an associated fee.

- Asian Health Services, Hill Country Health and Wellness, and San Ysidro Health are just a few of the California Community Health Center (CHC) practices that have invested heavily in this strategy.

- Reduce barriers to enhance recruitment of licensed BH providers.

- Eliminate criteria that are barriers to employment for licensed and unlicensed associate social worker (ASW) clinicians, such as mandating full-time work, employee status, and in-person work. Recruit for any number of hours from anywhere in the state.

- Salud Para La Gente and Alexander Valley Health Centers use this strategy successfully by hiring licensed clinicians who live in different areas of California and are fully remote.

- Focus on associate social worker (ASW) recruitment.

- In California, ASWs are billable for the PPS rate for FQHCs since May 2020. Focus on recruitment of ASWs, who are less expensive than licensed clinicians, more likely to be bicultural and bilingual, and able to bill for the same rate as licensed clinicians. ASWs are required by the Board of Behavioral Sciences of California to have two to three hours of supervision a week; if supervision needs exceed the practice’s licensed clinician capacity, contract for outside supervision.

- Community Medical Centers, which has one of the most robust BH departments in California and one of the highest ratios of BH providers to PCPs, utilizes this strategy.

Implementation tips

Deepening integrated care may feel like a big lift and can appear overwhelming to staff. Practice leaders will need to emphasize shared values and develop a north star for care transformation. Leadership must regularly name the challenge of the scarcity of behavioral health providers, recognize the care team’s efforts to navigate that challenge, highlight the strategic importance of growing the team’s capacity to provide behavioral healthcare, and celebrate wins along the way.

See the below resources for examples of how this activity has been implemented.

Resources

KEY ACTIVITY #5:

Enhance Inreach and Outreach to Engage People in Behavioral Healthcare

This key activity involves the following elements of person-centered population-based care: proactive patient outreach and engagement; behavioral health integration.

Overview

Inreach means to do outreach to patients already within the practice. Most IBH departments in community clinic settings see less than 10% of total patients, marking a significant gap between those who need and those engaged in behavioral health care. Most practices have thousands of patients who are struggling with behavioral health symptoms and are not engaged in behavioral healthcare. Clearly communicating to patients within the organization about behavioral health conditions and the availability of BH services can help connect patients to needed treatment. Successful inreach uses language and media that reflects the preferences of different populations served by the practice.

Outreach is connecting outside of the organization and the practice’s established patients to engage people with behavioral health needs in care. This is typically done in partnership with other community agencies, schools, emergency departments and other organizations.

Practices can begin by enhancing and expanding inreach to engage more of their established population with behavioral health needs in care. As capacity grows, practices can work with partner organizations to expand outreach activities. Note that engaging in inreach or outreach strategies is only feasible when there is behavioral health capacity to offer patients; see Key Activity 4: Develop Strategies to Maximize Capacity of IBH Services.

One of the distinguishing factors between population behavioral health and usual care is the commitment to providing care and services to those not already engaged. Population behavioral health takes into account all patients in the organization (inreach) and all people in the community (outreach), assesses how many people need behavioral healthcare, and develops strategies to proactively engage people in care.

Inreach and outreach are informed by a variety of data and information sources and do not rely solely on individual referrals. Using secondary data sources, existing community assessments, and information from partner organizations (outreach) and data from the EHR and the local health plans (inreach), the practice will be able to identify, prioritize, and implement meaningful interventions to engage patients in behavioral healthcare.

Proactive inreach and outreach, when intentionally focused on communities that have experienced racism, bias and discrimination, is a crucial intervention to eliminate health inequities. Through inreach and outreach, organizations can develop specific strategies to engage particular groups or communities by providing information and a welcoming environment to patients of historically underserved and under-resourced groups inside and outside the practice. This is best done in collaboration with staff (inreach) and community partners (outreach) who are representative of and trusted by the community.

Health-related social needs (e.g., income insecurity, transportation issues, and health literacy) can result in no-shows and deterioration of patient health status. Proactive inreach and outreach, coupled with awareness of health-related social needs, can facilitate connecting patients to community resources and developing greater trust in the care team.

Recognizing that trauma and its sources can lead to lower engagement, consider identifying a staff member or peer leader who is very skilled in empathic listening to reach out to patients to learn what gets in the way of engaging in behavioral health services, as well as the supports that they would most appreciate and would be most effective. This could be through email or text, phone, in-person conversation, or in focus groups. Health centers have different care team members fill this role, including community health workers, health educators, medical assistants, medical social workers, care coordinators and managers.

This activity relies on similar capabilities as care gap management, utilizing population views and registries to identify patients who would benefit from behavioral health engagement. These registries can be utilized to generate inreach and outreach lists for care team members who might be tasked with engaging patients in behavioral health services. Many EHRs can store next-appointment data that can also be used to generate lists supporting these efforts. In addition, EHR alerts and prompts can be leveraged to identify patients for engagement. Care managers and/or behavioral health team members might use care management applications to document engagement efforts.

Other relevant HIT capabilities to support this activity include clinical decision support and communication platforms, such as texting. Some health centers may focus extra resources on patients identified as having elevated risk through risk stratification algorithms.

Action steps and roles

1. Understand the behavioral healthcare needs of the practice’s patients and community patients.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Population health staff, data analyst, clinical leaders.

- Inreach: Mine practice data and local health plan data to better understand health inequities, patterns of use, and unmet needs of the practice’s population. The following suggestions are potential options for analysis and over time your team will determine which data sources illuminate your patient population’s health inequities, using patterns and unmet needs.

- Review practice data for opportunities to improve BH engagement for existing patients. Data of particular interest may include, for example, the number of patients engaged with BH over the last 12 months, by race or ethnicity; the number of patients on psychotropic medications with no behavioral health visits; the percent of postpartum patients engaged in BH in the last year; patients with positive scores on depression, anxiety, ACE and SUD screenings in the last year with no behavioral healthcare; or patients with more than two ER visits in the last year.

- Partner with local health plans to gather data on the practice’s patient population with regard to BH needs. Examples of BH-related data from health plans include patients’ emergency department usage, hospitalizations, pharmacy claims for opioids or any psychotropic medication, and patients assigned to the practice with no visit in the last year, etc.

- Outreach: Partner with community leaders, state agencies or professional bodies to obtain data on BH conditions in your area.

- Initiate or strengthen connections to county behavioral health departments, community-based social needs organizations, schools, hospitals, and faith groups. Let potential partners know that you are interested in improving access to BH services and ask them if they would participate in a conversation with you about what they see as the priority needs in the community. The conversation might start with a simple question like, “In your experience, what BH needs are unmet in your client or patient population?” As the partnership takes shape, establish regular meeting times, communication norms and other relational strategies. Consider business agreements or other formal arrangements to share data.

2. Develop or enhance inreach and outreach to all patients and community members, prioritizing patient preference, dignity, autonomy and readiness.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Clinical leaders, operation managers, staff.

Inreach strategies include:

- Develop patient-facing materials in the languages of populations served. Examples include:

- Posters for the waiting room, which list common BH concerns, BH services at the practice, and how to make an appointment with a BH provider.

- Pamphlets about high-prevalence BH conditions, such as depression, anxiety, ACEs and SUD; include the practice’s IBH information and how to make an appointment.

- Text blasts or telephone hold messages that inform patients that BH services are available and how to make an appointment.

- Develop a list of patients with BH needs using data reports (examples above) from the EHR or the health plan, then assign skillful BH case managers or care coordinators to call patients on the list and offer them BH services.

- Using data reports, have a medical assistant or other staff add alerts or other prompts within the EHR for patients on the list to indicate to staff and providers to discuss and offer BH services when they next come in for care.

- Collaborate with leaders and staff in other departments to develop specific inreach strategies for subpopulations with high behavioral health needs (e.g., patients obtaining medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid use disorder, pregnant and postpartum patients, or patients with chronic pain).

- Develop standardized clinical pathways for subpopulations of focus (e.g., automatic referrals for patients who score positive on BH screening tools, have chronic pain, or with a recent discharge from the ER).

- Employ inclusive communication methods grounded in cultural humility. Language that is congruent with patient preference is the first step. Utilize EHR data to align the communication method (e.g., call, text, email) with patient preferences.

- Select staff to carry out inreach based on the strength of the existing relationship with the patient group of focus (e.g., selecting Comprehensive Perinatal Services Program (CPSP) staff for inreach to pregnant and parenting patients; the cultural and language congruence with the patients of focus; and the available time of the staff.

- Ensure all inreach activities prioritize patient autonomy. Inreach explains BH services and offers BH services; the nature of inreach is supportive, not mandatory.

- Ensure inreach activities take into account patient preferences. When patients receive care aligned with their preferences – both location and type of treatment – adherence is higher and health outcomes are improved.[24]

Outreach strategies include: