©️ 2024 Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, Inc.

This guide provides step-by-step guidance for improving population-based care for children with the goal of supporting substantive cultural, technological, and process changes, focusing on child immunization status, well child visits in first 30 months of life, child and adolescent well care visits, and immunization for adolescents.

This guide was designed as part of the Population Health Management Initiative (PHMI), a California collaboration of the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS), Kaiser Permanente and Community Health Centers. Much of the content is relevant and adaptable to primary care practices of all kinds working to improve the health of the populations they serve.

Preventive screenings and care for children and adolescents reduce the risk of disease that can lead to disabilities and premature mortality. However, many in the United States do not utilize suggested preventive healthcare services.[1]

In the case of children, regular well-child check-ups are essential to monitor growth and identify potential health issues at early stages when intervention is often more effective. Screenings and vaccinations play a pivotal role in upholding the well-being of individuals spanning various age brackets.[2][3]

This guide provides practices with detailed guidance, examples, resources and tools to develop, test, refine, bring to scale, and continually improve protocols around children’s immunization and well-child visits (WCVs). This guide is designed to be helpful as part of an organized quality improvement strategy, with the goal of supporting substantive cultural, technological and process changes that improve population-based care for pediatrics.

The guide lists several key activities by section:

- Foundational activities: The core activities that all practices must implement as part of their children’s immunization and WCV protocol.

- Going deeper activities: More advanced activities that build off the foundational activities and further your efforts to achieve equitable improvement in your children’s immunization and WCV rates.

Sequencing activities: We recommend that practices consider planning and attempting to implement the activities in the sequence provided in this guide. At the same time, we recognize that different practices may follow a different path toward prioritizing and implementing these activities. Furthermore, there is a lot of overlap between activities; many activities build off of or from the building blocks of other activities.

Testing and implementing: For each activity we provide guidance on how to plan, test and implement the activity along with links to other resources, technology considerations and examples. Consider testing different versions of the action steps and roles on a small scale before fully implementing at your practice.

Maintaining the progress: For many activities we have also provided tips for periodically reviewing and making improvements to key workflows even after initially implementing the change. Ongoing review and continual improvement are important for your practice to maintain your progress in population health management and help you stay nimble in adapting to changing patient demographics, new clinical best practices, new payment policies, workforce changes, and other changes at your practice.

If you implement the foundational activities in this guide, you should be able to achieve the following foundational competencies:

For pediatrics, your practice will be able to consistently:

- Engage patients served by your practice to validate any proposed process improvements and to learn alternative methods to improve quality in your focus area.

- Analyze core quality measures to identify disparities and improvement opportunities for adherence to American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) preventive care guidelines year over year among attributed patients.

- Incorporate AAP preventive care guidelines into well-child visit protocols for infancy and early childhood (up to 30 months).

- Create an outreach protocol to reach and engage all attributed patients due for care.

- Prepare for integrating behavioral health follow-up services as needed.

- Create a health-related social needs screening process that informs patients’ treatment plans.

- Assess current capabilities and develop a plan for ongoing improvement in data utilization, care team workflows and efficiency that includes sustainable health information technology (HIT) strategies and continuous staff training on technology.

This guide also includes sections on measurement, equity, social health, behavioral health integration and an appendix including helpful tools and resources. We have included information about California Medi-Cal covered benefits and services that were up-to-date at the time of publishing, but benefits and billing guidance change over time. Nothing in this guide should be considered formal guidance, and anyone using this guide should check with the appropriate authorities on benefits and billing guidance.

This is a living document and will change based on continued learning on this topic and may include additional activities, examples, resources and sections in the future.

Improving the health of a population impacts everyone in a practice. Critical roles needed to engage in the work outlined in this guide and support practice change include:

- Quality improvement leadership, like a director of quality improvement (QI) or additional team leads (e.g., clinical, front office, etc.), to support cultural changes.

- Coaches or practice facilitators who are partnered with teams to help identify areas for improvement and support change through change management strategies.

Putting the Key Activities in Context

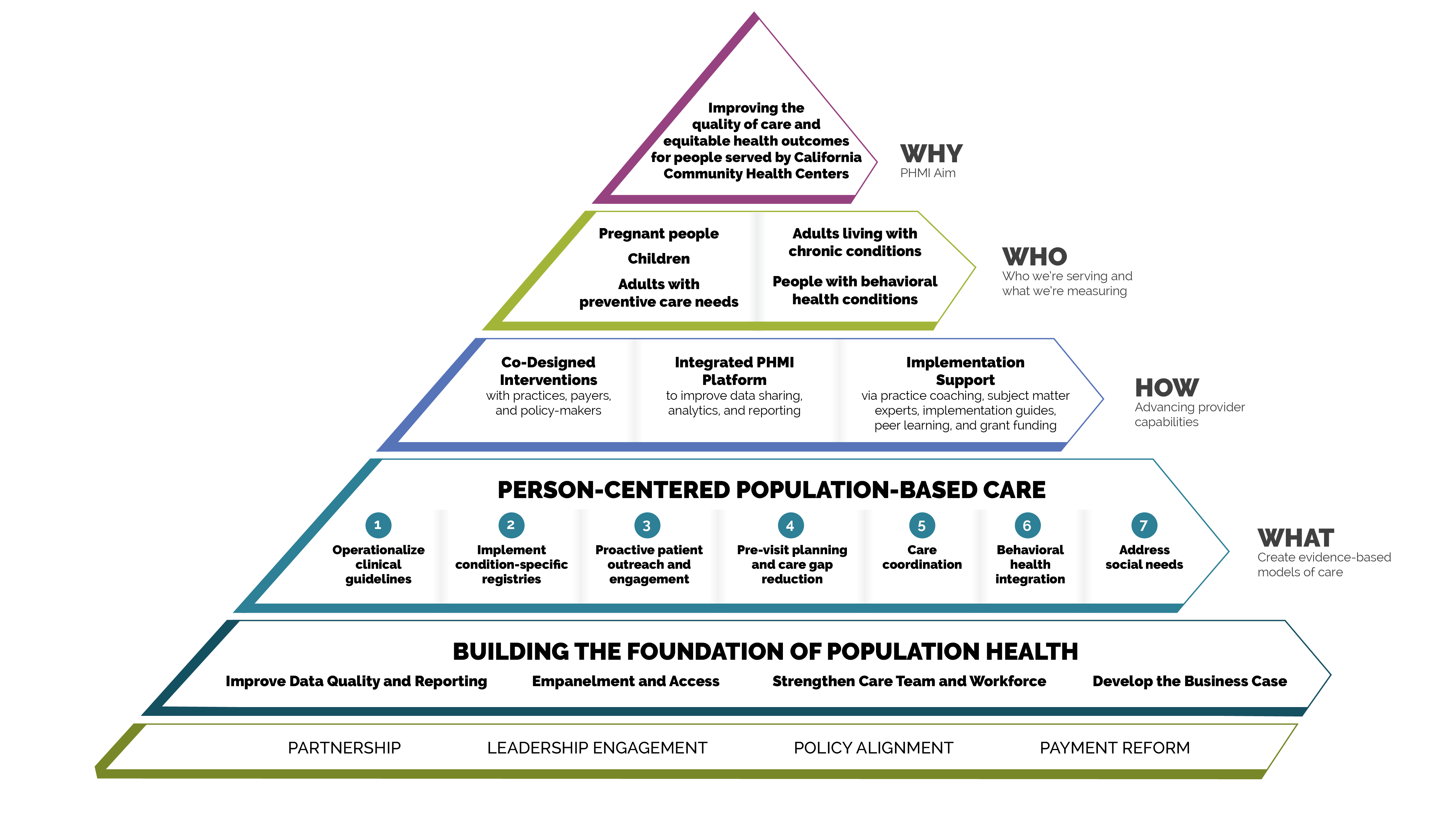

Person-centered population-based care

Each of the key activities advance one or more of the seven person-centered population-based care change concepts:

- Operationalize clinical guidelines.

- Implement condition-specific registries.

- Proactive patient outreach and engagement.

- Pre-visit planning and care gap reduction.

- Care coordination.

- Behavioral health integration.

- Address social needs.

FIGURE 1: PHMI IMPLEMENTATION MODEL

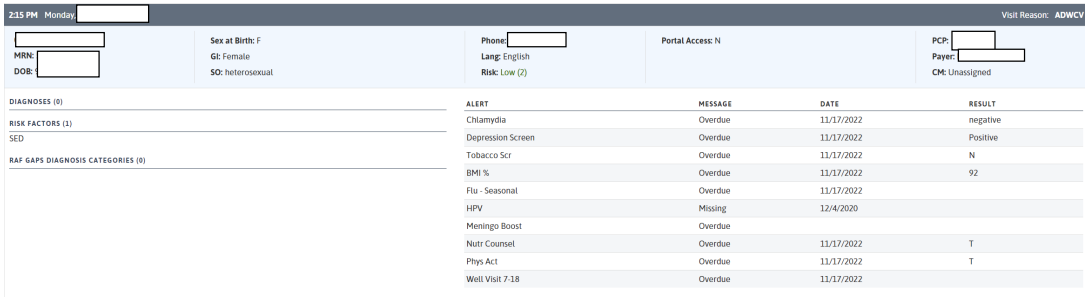

The measures covered in this guide consist of Healthcare Effective Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures designated as core and supplemental measures by the Population Health Management Initiative (PHMI). All measures use standard HEDIS definitions and are aligned with California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Cal (CalAIM) and Alternative Payment Methodology (APM 2.0). For information about these measures, reference the Data Quality and Reporting Guide.

PHMI selected a few core and supplemental measures of focus for this population, though practices can track others that feel important and relevant. This guide provides detailed guidance to improve your practice’s results on the following two core measures and three supplemental measures for adolescents and families:

- Childhood Immunization Status (core measure).

- Well-child Visits in First 30 Months of Life (core measure).

- Child and Adolescent Well-Care Visits (supplemental measure).

- Immunization for Adolescents (Combo 2) (supplemental measure).

- Well-child Visits in First 30 Months of Life (15 to 30 months) (supplemental measure).

CORE HEDIS MEASURES FOR PHMI

PHMI Population of Focus |

Measure |

|---|---|

Children |

Childhood Immunization Status Percentage of two-year-old children who have received the 10 reported vaccines* *As of October 2023, there are 11 recommended vaccines. However, the RSV vaccine has not yet been incorporated into HEDIS measures. |

|

Well-Child Visits in First 30 Months of Life Percentage of children who have had six or more well-child visits in their first 15 months of life. |

SUPPLEMENTAL MEASURES FOR PHMI

PHMI Population of Focus |

Measure |

|---|---|

Children |

Child and Adolescent Well-Care Visits Percentage of children three to 21 years of age who received one or more well-care visits with a primary care practitioner or an OB/GYN practitioner during the measurement year. |

|

Immunization for Adolescents (Combo 2) Percentage of adolescents 13 years of age who had one dose of meningococcal vaccine, one Tdap vaccine and the complete human papillomavirus (HPV) series (i.e., two doses separated by 6-12 months) by their thirteenth birthday. |

|

|

Well-Child Visits in First 30 Months of Life (15 to 30 months) Percentage of children who turned 30 months old during the measurement year, and had at least two well-child visits with a primary care physician in the last 15 months. |

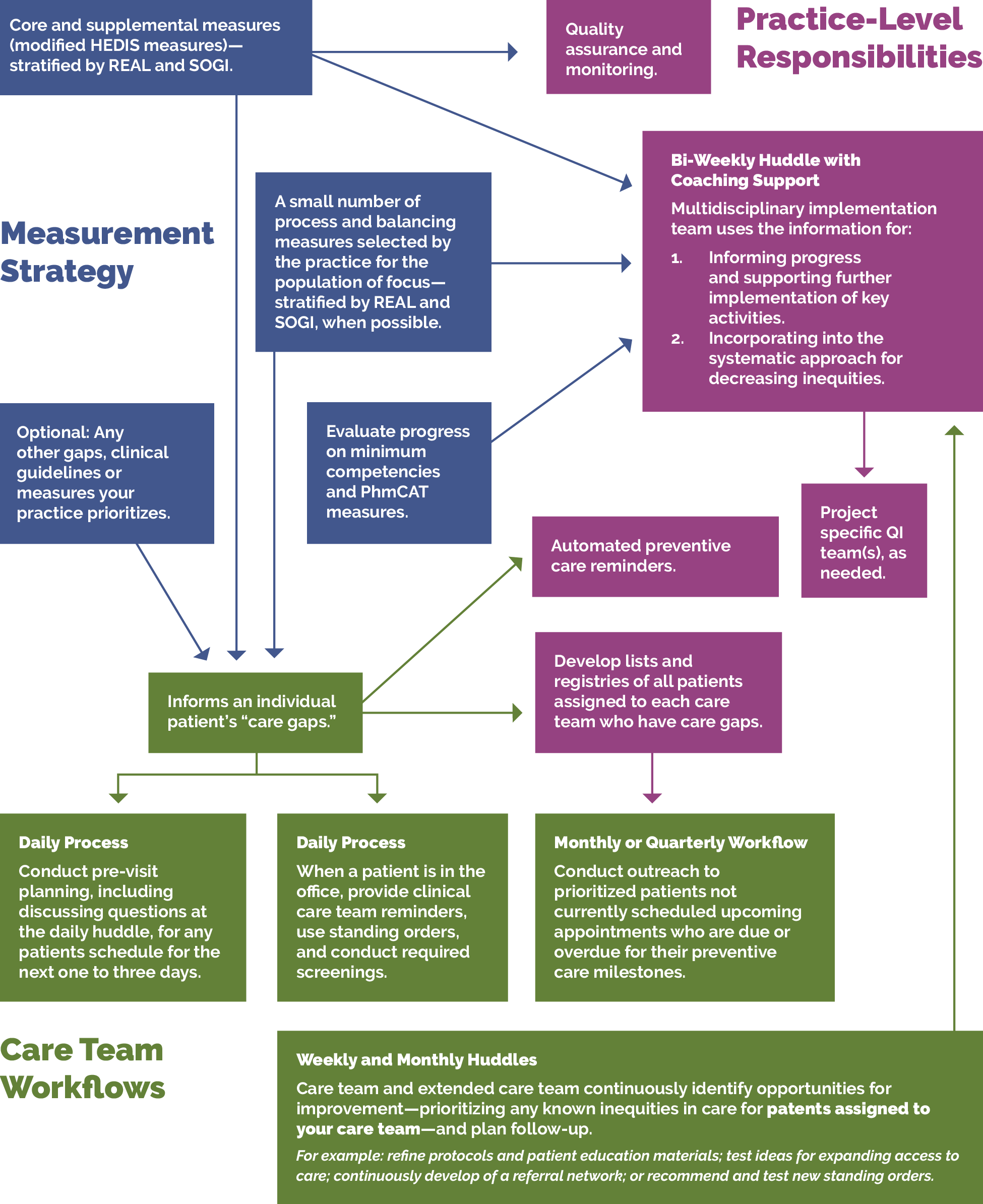

The core and supplemental measures are part of a larger measurement strategy and learning system, as outlined in Appendix A: Sample, Idealized System Diagram: Weaving Your Measurement Strategy and Learning System into Practice Operations. Key Activity 1: Convene a Multidisciplinary Implementation Team Focused on Pediatrics outlines how your practice can develop a robust measurement system to support this work. In addition to quality assurance and monitoring, these measures are also used during practice operations alongside other data for learning to:

- Guide the actions of the multidisciplinary implementation team as they use a systematic approach to decreasing inequities and support implementing key activities across the practice.

- Support the individual care team’s efforts to advance population health and reduce care gaps through daily, weekly and monthly workflows, as well as continuous identification of opportunities for improvement.

The PHMI Clinical Guidelines Advisory Group (CGAG) was established to create a standardized approach to review, adopt and promote established clinical guidelines in the PHMI cohort. For pregnant people, guidance includes prenatal care initiation and prenatal and postpartum depression. For more information, please see the Clinical Practice Guidelines for Key Medi-Cal Populations of Focus.

FIGURE 2: CLINICAL GUIDELINES: WELL-CHILD VISITS IN FIRST 30 MONTHS OF LIFE (FIRST 15 MONTHS)

Guideline source |

|

PHMI measure |

Well-Child Visits in First 30 Months of Life (First 15 Months) |

Definitions |

Well-child visit (WCV): The WCV must occur with a primary care provider (PCP), but that PCP does not have to be the practitioner assigned to the child. Documentation includes all five of the following components:

|

Guideline language |

Conduct WCVs as a newborn; at three to five days old; by one month; and then at two, four, six, nine, 12 and 15 months. If a child comes under care for the first time at any point on the schedule, or if any items are not accomplished at the suggested age, the schedule should be brought up to date at the earliest possible time. |

FIGURE 3: CLINICAL GUIDELINES: CHILD AND ADOLESCENT WELL-CARE VISITS

Guideline source |

|

PHMI measure |

Child and Adolescent Well-Care Visits |

Definitions |

Well-child visit (WCV): The well-care visit must occur with a PCP or an OB/GYN practitioner, but the practitioner does not have to be the practitioner assigned to the individual. Documentation includes all five of the following components:

|

Guideline language |

Conduct annual well-care visits for persons three to 21 years of age. |

FIGURE 4: IMMUNIZATIONS FOR ADOLESCENTS

Guideline Source |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (2024) |

PHMI Measure |

Immunizations for Adolescents (IMA) |

Guideline Language |

|

Many key activities in this guide include considerations for utilizing the intervention to improve equitable health outcomes and reduce the effects of racism, bias and discrimination. Key Activity 4: Use a Systematic Approach to Decrease Inequities describes key action steps for how to make an intentional and explicit effort to identify inequities, understand root causes, and reduce those inequities. Refer to existing data sources and reports that illuminate existing inequities, such as the 2021 Health Disparities Report.

This guide also offers resources for going deeper into organizational and ecosystem-level work to advance equitable outcomes such as what is outlined in Key Activity 20: Strengthen a Culture of Equity. More information about this approach can be found in the PHMI Equity Framework and Approach.

Integrated behavioral health supports are important for children and their caregivers, as behavioral health support is likely to boost health outcomes and enhance patients' quality of life. One foundational change is to ensure that the care team includes behavioral health staff as core members of the team. This is covered in detail in the Care Teams and Workforce Guide.

For children, foundational key activities for integrating behavioral health include Key Activity 7: Attending to Social and Emotional Development During WCVs and Key Activity 8: Providing Dyadic Care: Screen for Postpartum Depression. Throughout these and other key activities in this guide, we have incorporated considerations for providing trauma-informed care, detailed in Key Activity 10: Implement Trauma-Informed Care Approach Across the Patient Journey. For going deeper in behavioral health integration, practices can refer to Key Activity 17: Expand Dyadic Care to Provide More Comprehensive Social and Behavioral Health Services, and Key Activity 18: Continue to Develop Referral Relationships and Pathways for specialized behavioral health services.

Of note for California Medi-Cal, there are multiple considerations and complexities in integrating behavioral health. As one example, the behavioral health benefit is divided into mild to moderate versus severe mental health conditions; the clinicians qualified and contracted to provide this care are often different. As such, early on in the behavioral health evaluation process, a clinician must decide whether a client is at the mild to moderate or severe end of the spectrum. For mild to moderate, the Medi-Cal Managed Care Plan (MCP) provides the benefit, whereas for severe, the county mental health system is responsible.

The AAP/Bright Futures recommends integrating social drivers of health into primary care to assess family access to resources necessary for optimal child development.[4] For many key activities in this guide, we have highlighted considerations related to social needs at the individual or population level, such as expanding clinic hours. A foundational activity is Key Activity 7A: Develop a Screening Process for Social Needs and Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES) that Informs Patient Treatment Plans which can help practices better understand and support patient- and population-level needs. Practices can help patients and families and make connections to resources in the community to address issues such as childcare, parenting, legal and health education needs. For Medi-Cal patients and families with high levels of social need, such as those experiencing homelessness, referrals to Enhanced Care Management (ECM) and Medi-Cal Community Supports services are available; see Key Activity 19: Provide Care Management for more.

For going deeper in this area, practices can refer to Key Activity 18: Develop Referral Relationships and Pathways for common social needs Key Activity 15: Strengthen Community Partnerships to build upon the strengths, infrastructure and resources available in the community. More information about this dual patient- and population-level approach is available in the PHMI Social Health Framework and Approach.

Foundational Key Activities

These are the core activities that all practices must implement as part of their children’s immunization and WCV protocols.

KEY ACTIVITY #1:

Convene a Multidisciplinary Implementation Team Focused on Pediatrics

This key activity involves all seven elements of person-centered population-based care: operationalize clinical guidelines; implement condition-specific registries; proactive patient outreach and engagement; pre-visit planning and care gap reduction; care coordination; behavioral health integration; address social needs.

Overview

This activity provides guidance for developing, launching and sustaining the team or task for within your practice that will be responsible for the planning and implementation of all of the foundational key activities in this guide and overseeing related quality improvement and equity efforts, as outlined in Appendix A: Sample Idealized System Diagram.

The implementation team is so important that it appears first in our sequenced list of foundational activities. Improving your practice’s key outcomes for each population of focus and reducing equity gaps requires the aligned efforts of all care teams and nearly all functional areas of the practice, not just those working directly with patients.

This team is responsible for ensuring that the foundational key activities in this guide, including those related to screening for social needs, are implemented. As a minimum standard for screening for social needs, consider addressing social needs included in the areas recommended by the AAP/Bright Futures periodicity schedule.

In identifying potential members of this multidisciplinary implementation team, the practice should identify a diverse group of staff who are reflective of the community served and who represent the lived experience of patients. Practices may also consider mechanisms for ensuring that patients and families are informing the decisions and actions of the multidisciplinary implementation team, including but not limited to embedding patients and/or family members on the team and creating an active patient and family advisory group, all of whom are paid for their expertise and time in compliance with any relevant local, state, or federal laws and regulations.

In addition to implementing the key activity focused on applying a systematic approach to decrease health inequities, the team should apply a trauma-informed care approach and equity lens to every step outlined in this guide to help ensure that any improvements are equitably spread among the patient population. See Key Activity 10: Implement Trauma-Informed Care Approach Across the Patient Journey for further guidance. To achieve optimal functioning and impact, all members of this diverse multidisciplinary team should have their perspectives proactively included.

Relevant health information technology (HIT) capabilities to support this activity include care guidelines, registries, clinical decision support, care dashboards and reports, quality reports, outreach and engagement, and care management and care coordination (see Appendix D: Guidance on Technological Interventions). To enable team coordination, thought must be given to how to access relevant technology and how data is consistently captured, can be distributed, integrated into workflows, and how data is accessible across team members. Where possible, it is desirable to avoid duplication of data entry, siloing of information in standalone applications and databases, and the need to work in multiple applications requiring separate login.

Action steps and roles

1. Develop a time-limited group of leaders within the practice to start this process.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Chief medical officer or equivalent and office manager or quality improvement (QI) coordinator.

Start with a small group of leaders from your practice, some of whom will be on the implementation team. These people will help refine the charge or scope of work of the implementation team and identify and engage the people and roles that will be required to implement the scope of work of the team.

2. Develop a preliminary scope of work or charge outlining the responsibilities of the implementation team.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Time-limited group of practice leaders.

This scope or charge includes (but may not be limited to) enabling, aligning, leveraging and supporting the planning and implementation of all foundational key activities in this implementation guide so that the practice meets the foundational competencies.

However, there may be further foundation building work needed at your practice in order for you to succeed at the above key activities. The Population Health Management Capabilities Assessment Tool (PhmCAT) is a multidomain assessment that is used to understand current population health management capabilities of primary care practices. This self-administered tool can help your practice identify opportunities and priorities for improvement.

If your practice has not scored high in the domains of leadership and culture, the business case for population health management, technology and data infrastructure, or empanelment and access, consider implementing the activities listed in the four guides on Building the Foundation before or in parallel to working on key activities related to pediatrics.

3. Identify leadership and key actors for the implementation team.

Suggested staff responsibilities: Time-limited group of practice leaders.

The multidisciplinary implementation team should include those empowered to make changes in workflows, policies and staff assignments. They should be respected influencers in the organization (early adopters) who can also guide the change management process.

- Appoint a champion or lead person (e.g., pediatric prevention coordinator) to oversee the implementation and coordination of the team.

- Identify key actors who will be the core members of the implementation team. This could include a core team and an expanded team. Potential members include.

- Pediatricians.

- Medical assistants.

- Panel managers.

- Quality improvement lead.

- Community health workers and other community outreach staff.

- A member of the information technology (IT) or electronic health record (EHR) team (as part of the expanded team).

- Billing manager or similar (as part of the expanded team).

- A data lead.

- A frontline staff member who interfaces with patients by phone and at check in.

- Invite identified people to become part of the implementation team and ensure that they have designated time for their participation.

4. Launch the implementation team and set it up for success.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Clinical coordinator or chief operating officer (COO) or chief medical officer (CMO).

This work includes:

- Ensuring that the team understands their charge or scope of work and developing a outlining this work: see the Multidisciplinary Implementation Team Charter Template.

- Defining roles and responsibilities, including the anticipated commitment (in hours) on a monthly basis.

- Establishing a meeting structure, file structure and communications structure to support effective, efficient work.

- Dedicating time and effort to forming, storming, norming and performing as a team. The Team Communication and Working Style Template is one tool that team members can complete and share with other teammates to accelerate this process.

- Understanding baseline data related to outcomes of interest (e.g., baseline immunization rates, baseline well-child visit completion rates), along with data related to known and perceived barriers to these outcomes.

- Prioritizing elements within the scope of work, informed by baseline data and identified population needs.

- We recommend that practices consider planning and attempting to implement the activities in the sequence provided in this guide, focusing first on the foundational activities before focusing on the activities noted as Going Deeper activities. However, different practices may follow different paths toward implementation.

5. Develop a simple yet robust measurement strategy and learning system to guide your improvement efforts.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Implementation team.

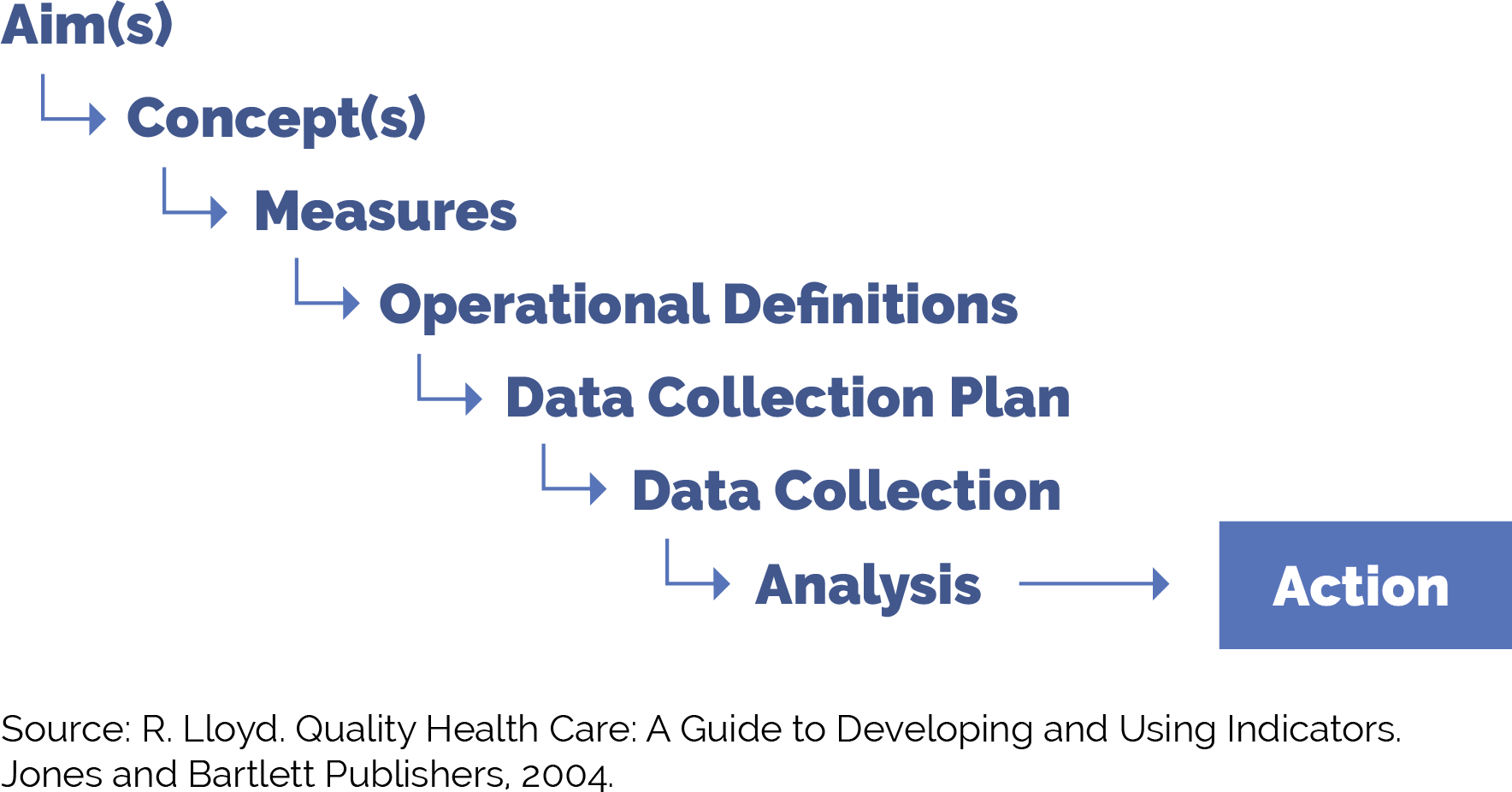

A learning system enables a group of people to come together to share and learn about a particular topic, to build knowledge, and to speed up improved outcomes. A simple yet robust measurement strategy and learning system:

- Contains a balanced set of measures looking at outcomes, processes and possibly unintended secondary effects (e.g., increased cycle time and impact on team well-being).

- Incorporates the patient perspective and the perspective of staff (front desk and others), care team members, and management.

- Allows the team to determine if the process or system has improved, stayed the same, or gotten worse.

- Helps guide improvement efforts and informs practice operations. See Appendix A: Sample Idealized System Diagram: Weaving Your Measurement Strategy and Learning System into Practice Operations for a sample system diagram for how your measurement strategy can be used to support practice operations.

Your practice should track the core and supplemental measures for childhood immunization status, well-child visits in the first 15 and 30 months of life, well-care visits, and immunizations for adolescents. These highly endorsed well-child and immunization guidelines can be considered proxy measures for outcome measures for improved child health.

In addition to the core and supplemental measures, practices should track process measures and balancing measures. Appendix C: Developing a Robust Measurement Strategy describes and defines the key milestones in the development of a robust measurement strategy, including definitions for each of these terms

Suggested process measures:

- Percentage of children zero to 30 months of age who were sent a reminder for recommended immunizations during the measurement year.

- Percentage of children five years of age who were sent a reminder for recommended immunizations during the measurement year.

- Percentage of children zero to 21 years of age who are identified as missing one or more recommended immunizations during the measurement year. For greater clarity and more actionable insights, also track completion rates by vaccination, such as:

- Percentage of children 21 months of age who are identified as missing one or more tetanus, diphtheria, acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccines.

- Percentage of children 21 months of age who are identified as missing one or more inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) vaccines.

- Percentage of children 18 months of age who are identified as missing one or more measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccines.

- Percentage of children 18 months of age who are identified as missing one or more Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccines.

- Percentage of children nine months of age who are identified as missing one or more hepatitis B (Hep B) vaccines.

- Percentage of children six months of age and older who are identified as missing the annual influenza (flu) vaccine.

Suggested balancing measures:

- One or more measures related to patient satisfaction.

- One or more measures related to staff satisfaction.

Practices can also look at other metrics to understand the progress of specific improvement initiatives over time. This may include:

- Progress on the Population Health Management Capabilities Assessment Tool (PhmCAT).

- Progress towards foundational competencies listed in this implementation guide. For example: “Yes or No: Did your practice achieve the following foundational competency: ‘Create a health-related social needs screening process that informs patients’ treatment plans.’”

- Any other care gaps, clinical guidelines or measures your practice feels are important to prioritize.

Applying an equity lens

Your practice may be achieving better outcomes with some patients than others. To understand these disparities, practices should stratify their data based on race, ethnicity and language (REAL), sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI), and other patient characteristics (e.g., social needs, etc.). The advancing equity through data quality and reporting section of the PHMI Data Quality and Reporting Guide provides more guidance on this.

Putting it all together

We recommend that your practice record your measurement strategy in one place. This Measurement Strategy Tracker contains all the fields we believe are most useful, and it can be customized to meet your practice’s needs.

6. Plan and hold regularly scheduled meetings of the implementation team.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Team lead or clinical coordinator or other individual tasked with coordinating the work of the team.

Hold time on team members' calendars for standing meetings. Consider biweekly (twice monthly) meetings to start with. The frequency, duration and focus of these meetings may change as you consider additional populations or subpopulations and additional sites or locations and as the nature of the work changes.

Develop a system to efficiently report on all workstreams and track follow-up items. The Action Plan Template is a tool that can be used to focus your team around the foundational competencies and define responsibility for actions and steps to be taken for each project your team has prioritized to work on.

7. Make adjustments based on data from the team’s measurement strategy and feedback loops.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Implementation team.

Review data and feedback at least monthly, and adapt efforts as needed. Adaptation could include any or all of the following:

- Amending the charge or scope of work.

- Modifying meetings or meeting structures.

- Changing the team composition (adding or removing members).

- Refining key activities to better meet the needs of patients and practice staff, improve outcomes or reduce inequities.

- Modifying the measurement strategy and/or feedback loops to better understand what is and isn’t happening.

Create opportunities for celebrating small wins, progress and measured improvement.

On an annual basis, the team’s charter and core membership should be reviewed. As the goals of the implementation team are met, the team could disband, meet less frequently (e.g., twice per year), or fold this meeting into a similar standing meeting that occurs separately.

Resources

Health Center Quality Measurement Systems Toolkit

Health Alliance of Northern California created a summary crosswalk of measurement sets that provides an overview of alignment between measurement systems. It includes in-depth information on each Uniform Data System (UDS) or Quality Incentive Pool (QIP) clinical measure for childhood immunizations, immunizations for adolescents, well-child visits (zero to 15 months), well-child visits (three to six years), child and adolescent well care visits (three to 17 years), which are contained in a spreadsheet. The document also shares suggested clinical interventions and community interventions for childhood and adolescent immunizations status in rural northern California.

KEY ACTIVITY #2:

Assess and Improve Reliability in Meeting Well-Child Visit (WCV) Recommendations

This key activity involves all seven elements of person-centered population-based care: operationalize clinical guidelines; proactive patient outreach and engagement; pre-visit planning and care gap reduction; care coordination; behavioral health integration; address social needs.

Overview

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)/Bright Futures developed a set of comprehensive health guidelines for well-child care, known as the periodicity schedule. It is a schedule of screenings and assessments recommended at each well-child visit from infancy through adolescence. Each pediatric clinic should implement protocols to ensure all recommended activities and interventions for all children and families are addressed during WCVs.

Click here for the periodicity schedule detailing recommended activities at each well-child visit.

This foundational activity deals with assessing and then improving your practice’s reliability in implementing the guidelines in periodicity schedule. Of note, a recent thoughtful article published in Pediatrics proposes a population health framework to facilitate a redesign – with emphasis on care teams – for delivering the most evidence-based dimensions of pediatric preventive care. It doesn't solely rely on the traditional WCV as the sole venue in which key preventive services are delivered. The innovation proposed in this framework may prove impactful for patients and practices; currently, however, this approach does not align with the quality measurement framework of reporting the compliance rate with annual well-child visits.

Well-care visit activities are recommended to assess and support children’s healthy development and their ability to access needed supports to achieve their best possible health and well-being. Bright Futures compiled tables of evidence and rationale describing the high degree of certainty for guidelines included in the periodicity schedule.

It is likely that the quality and reliability of the recommended WCV activities will vary across clinics. Ensuring that every child benefits from every recommended activity across their childhood is an essential goal for pediatric clinics.

Due to racism, bias and discrimination, children of color and children from families with lower socioeconomic status are less likely to complete all WCVs and therefore benefit from all WCV activities.[5][6][7][8] Ensuring that every WCV is optimized can contribute to mitigating inequities in health and well-being experienced by children based on race, ethnicity and class.

Additionally, WCVs provide an opportunity to forge healthy, positive, strengths-based relationships with children, youth and their families. A trusted, caring relationship can provide a foundation for mitigating the deleterious and harmful effects of racism, bias and discrimination.

WCVs provide an opportunity for screening for and responding to unmet social needs as well as building the trusted relationship necessary for families to disclose unmet needs. An initial minimum standard for social need screening may be guided by the Bright Futures implementation tip sheet on integrating health-related social needs.

Relevant HIT capabilities to support this activity include electronic access to care guidelines, registries, clinical decision support, care dashboards and reports, quality reports, outreach and engagement, and care management and care coordination. See Appendix D: Guidance on Technological Interventions.

Access to outside data may be a consideration or requirement (e.g., California Immunization Registry (CAIR) immunization registry data, school health data, and data from other practices) as services received outside the health center may be part of compliance. While claims data provided by payors may be helpful in this regard, lag time may impact its usefulness. Partner Medi-Cal managed care plans (MCPs) likely already do or can provide upon request reports of children who appear overdue, based on claims and encounter data, for pediatric preventive care, such as well-child visits and lead screening. Such reports may reduce the need for health centers to generate reports from raw claims data. Patient-facing applications should be strongly considered to assure that parents, caregivers and older adolescents are informed and appreciative of the nature and importance of recommended care. Confidentiality concerns and regulatory requirements protecting emancipated adolescents can be challenging, as EHRs and other technologies may not support segmentation of information. This may need to be overcome through manual workarounds and procedures

Action steps and roles

1. Review current practices to identify key opportunities for improvement.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: QI lead with frontline staff (e.g., PCP, nurse, medical assistant, front desk staff).

Using the periodicity schedule as a guide, catalog the clinic’s current practices, processes and protocols related to WCVs. Identify how current practices align with the recommendations of the periodicity table and identify top opportunities for improvement.

Consider compiling additional data to determine the rate of completion of each of the recommended activities at each WCV, even if these data are from a small sample of WCVs (e.g., the next five to 10 WCVs for 15-month-olds). Review aggregated data to identify areas of strong performance to learn from and areas for improvement to prioritize. See more in Key Activity 3: Use Care Gap Reports or Registries to Identify all Patients Eligible and Due for Care.

Opportunities for improvement may include:

- Improving scheduling and completion rates for WCVs at the recommended ages.

- Introducing a practice, process or protocol that is currently not being done at all.

- Expanding the WCVs at which a practice, process or protocol is currently being done.

- Improving the quality or reliability of a current practice, process or protocol.

Of note, one of the more challenging Bright Futures and U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendations is the initiation of fluoride varnish after the eruption of the first primary tooth. A new HEDIS measure in 2023 for fluoride varnish reads, “The percentage of members one to four years of age who received at least two fluoride varnish applications during the measurement year.” While federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) with colocated dental clinics may have additional resources and flexibility regarding integration of this key pediatric preventive service, practices without colocated dental clinics may need to employ new strategies.

2. Test new and adapted practices and processes to develop improved workflows and standard protocols for implementing recommended activities during WCVs, focusing first on prioritized areas for improvement.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: QI lead with frontline staff, as appropriate for the WCV activity of focus; patients and their families.

Consider how to use registries, the pre-visit planning process, and daily huddles to support this key activity. (Note: Other key activities are included in this guide to support these aspects.) Use the individual WCV resource pages at AAP Schedule of Well-Child Care Visits – HealthyChildren.org to design, organize and improve each WCV. Consider how to integrate a trauma-informed approach as your practice creates and tests new or adapted processes and enlist caregivers as partners in ensuring WCV activities are provided on time. HealthyChildren.org provides a caregiver-friendly version of the AAP Schedule of Well-Child Care Visits that clinics can share with parents so they know what to expect.

3. Continuously improve approach to WCVs, both overall and for key subpopulations.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: QI lead with frontline staff, as above.

Track data on completion of WCVs in real time and collect disaggregated data by race and ethnicity, as well as by language spoken and geographies, whenever possible. Advocate for strategies that address the challenges specific to subgroups, particularly those with low WCV completion rates, to drive optimal WCVs for all children and families. See more in Key Activity 10: Implement Trauma-Informed Care Approach Across the Patient Journey and Key Activity 4: Use a Systematic Approach to Decrease Inequities.

Implementation tips

Below are examples of quality improvement efforts to improve reliability of meeting WCV recommendations:

- Sonoma Valley Community Health Center created a training booklet to both train new staff and act as a reference guide for existing staff. Updated annually, it contains many of the health center’s key workflows, including childhood immunizations.

- Shasta Community Health Center conducted an improvement project centered around increasing the rate of pediatric patients who leave an acute care visit with a scheduled well child visit from the baseline of 30%.

- Marin Community Clinics undertook a multipronged improvement effort for completing required immunizations for all patients by their second birthday by creating a culture of vaccinations at the practice.

- Hill Country Health & Wellness Center conducted a quality improvement project where they tested a new workflow for Childhood Health and Disability Prevention (CHDP) visits with one provider to optimize the use of provider time by segmenting the 40-minute appointment slot into two sessions. The first 20 minutes is with the licensed vocational nurse (LVN) or registered nurse (RN) for education, and the remaining 20 minutes is with the provider. This change was designed to increase access to well-child visits and deliver education on immunizations, thereby increasing immunization rates according to accepted periodicity schedules.

KEY ACTIVITY #3:

Use Care Gap Reports or Registries to Identify All Patients Eligible and Due for Care

This key activity involves all seven elements of person-centered population-based care: operationalize clinical guidelines; implement condition-specific registries; address social needs.

Overview

This foundational activity provides detailed guidance on how to reliably and efficiently develop and use a regularly updated list of all patients eligible for recommended or standard screenings or interventions through a care gap report or registry.

Care gaps are gaps between the recommended care that a patient should receive according to clinical guidelines and protocols and the care a patient has actually received. Rather than put the responsibility on the individual care team member for searching through charts or remembering which patients need further preventive care or follow-up, this key activity provides guidance for how the practice can efficiently leverage electronic health records (EHRs) and other applications or technical approaches for all its patients.

Care gap reports are essential for practices to understand and continually improve consistency and reliability for meeting guidelines for preventive care. At the care team level, care gap reports focus on gaps for patients assigned to your care team and help your team understand which patients you are responsible for. These lists can be used to:

- Support improvements to the pre-visit planning process, develop standing orders, and improve other routine clinical workflows designed to systematically identify and address gaps in care.

- Prioritize patients for whom care teams should provide proactive outreach and reminders for engaging in care.

- Support quality improvement efforts with an equity lens.

Actively identifying and acting on care gaps ensures all eligible patients assigned to your practice receive timely screenings and other preventive services.

Many practice patients and families experience barriers in accessing care due to structural and historical racism, homophobia, xenophobia, and other biases that have historically disadvantaged individuals and groups from receiving equitable services. Defining clear criteria and gaps for patients due for specific screenings or preventive services helps to illuminate groups who have not had equitable access. It also combats biases by standardizing expectations for what constitutes quality standards of care for all clients.

Staff can identify potential barriers to patients accessing and engaging in care by using enhanced care gap reports to filter and display the data alongside demographic information, social needs, behavioral health needs, and communication preferences. This information can be incorporated into a person-centered approach when designing the care plan, promoting self-care and other patient engagement activities, such as conducting outreach in the patients’ preferred language. Adopt a trauma-informed approach when designing, testing and implementing interventions to address potential barriers and gaps in care.

Furthermore, care gap reports that segment the data into cohorts based on demographic and other personal information may help the team identify disparities in care, access and outcomes, which can inform improvement efforts.

Care gap reports can be used during pre-visit planning to identify people for whom social needs screening has not yet been completed. This creates an opportunity to identify unmet social health needs and connect patients with resources that address their social needs.

Many EHRs already have a module that identifies what services are due for each patient, while others do not. Where this functionality is available, it may not be configurable to align with the health center’s specific protocol or be able to incorporate outside data. Other options for developing registries include supplemental applications, population health platforms, and freestanding customized databases that draw data from the EHR and other sources. A comprehensive approach to the use of care gap reporting may require multiple modalities.

A registry can be thought of simply as a list of patients sharing specific characteristics that can be used for tracking and management.

Care gap reports may be embedded in electronic health records or made available through other technology channels (see Appendix D: Guidance on Technological Interventions) and are useful both at the individual patient level and aggregated to identify groups of patients to facilitate population-level management through registries.

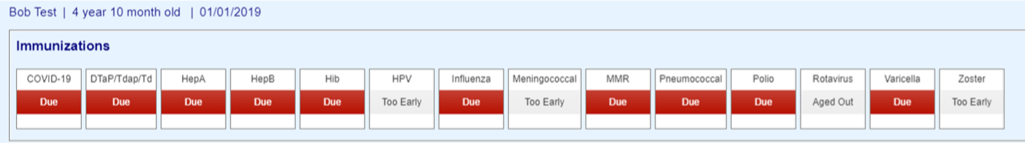

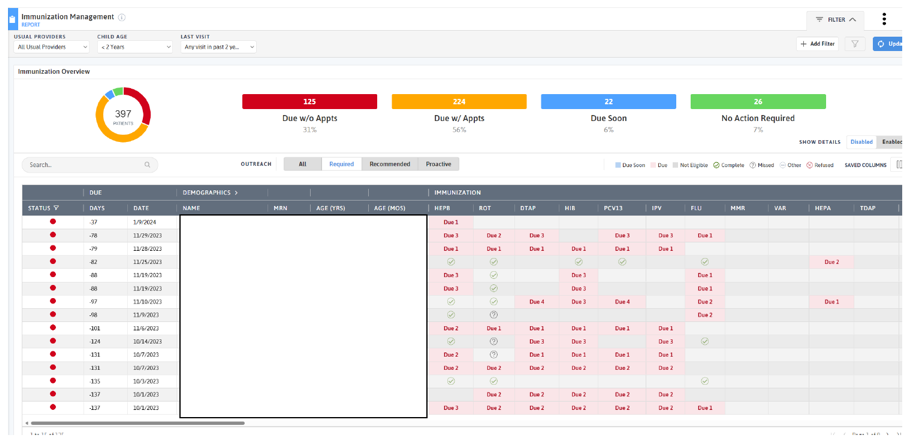

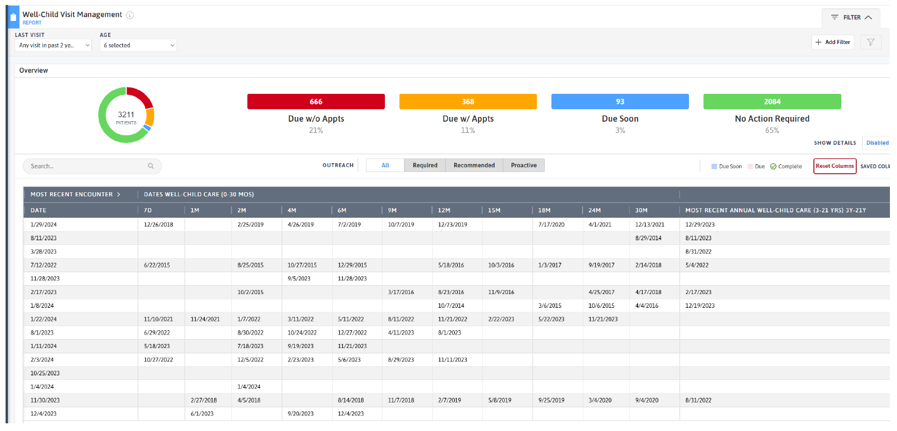

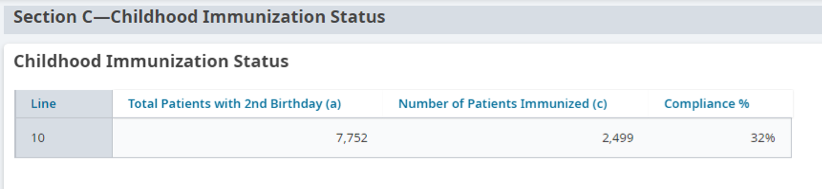

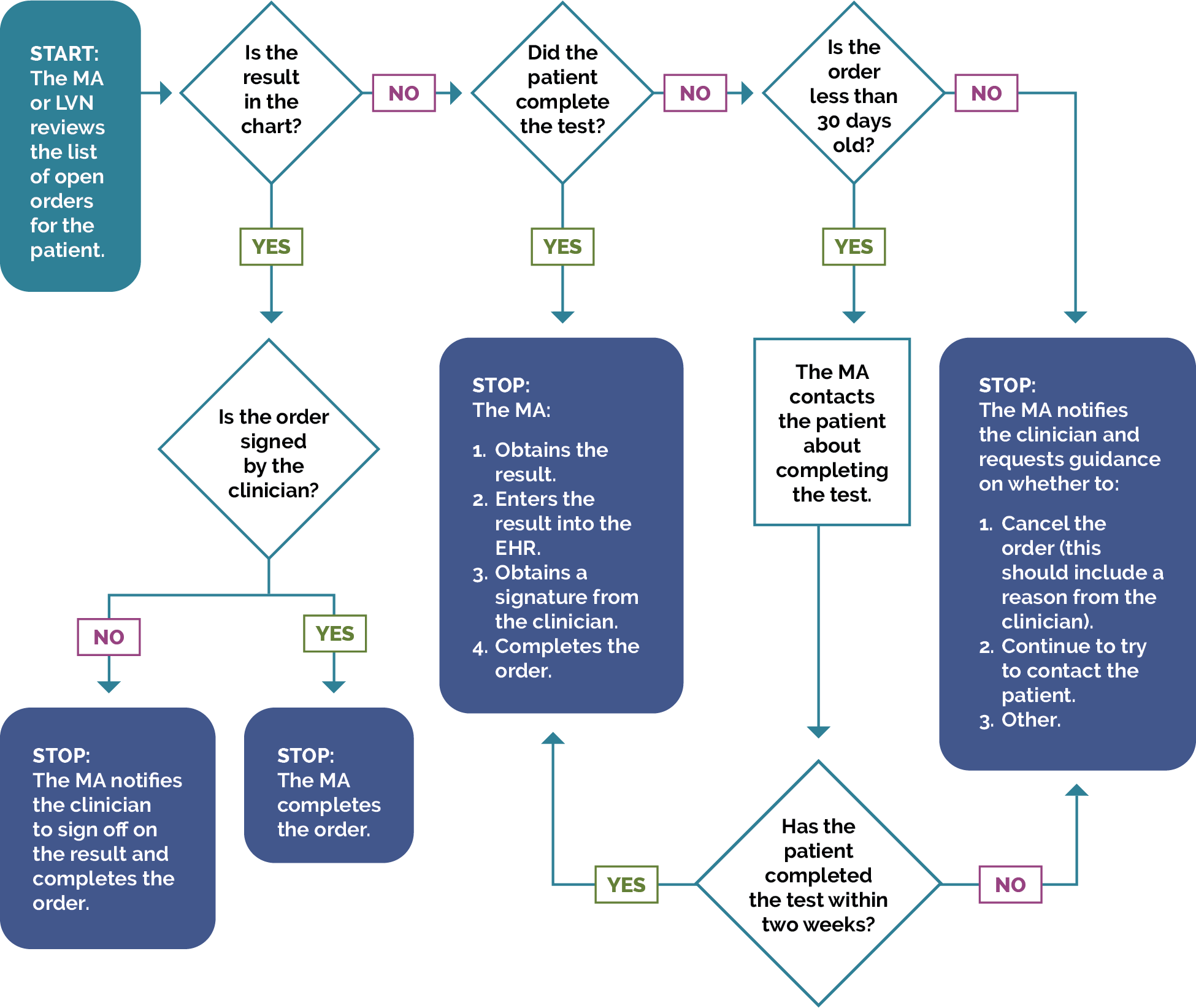

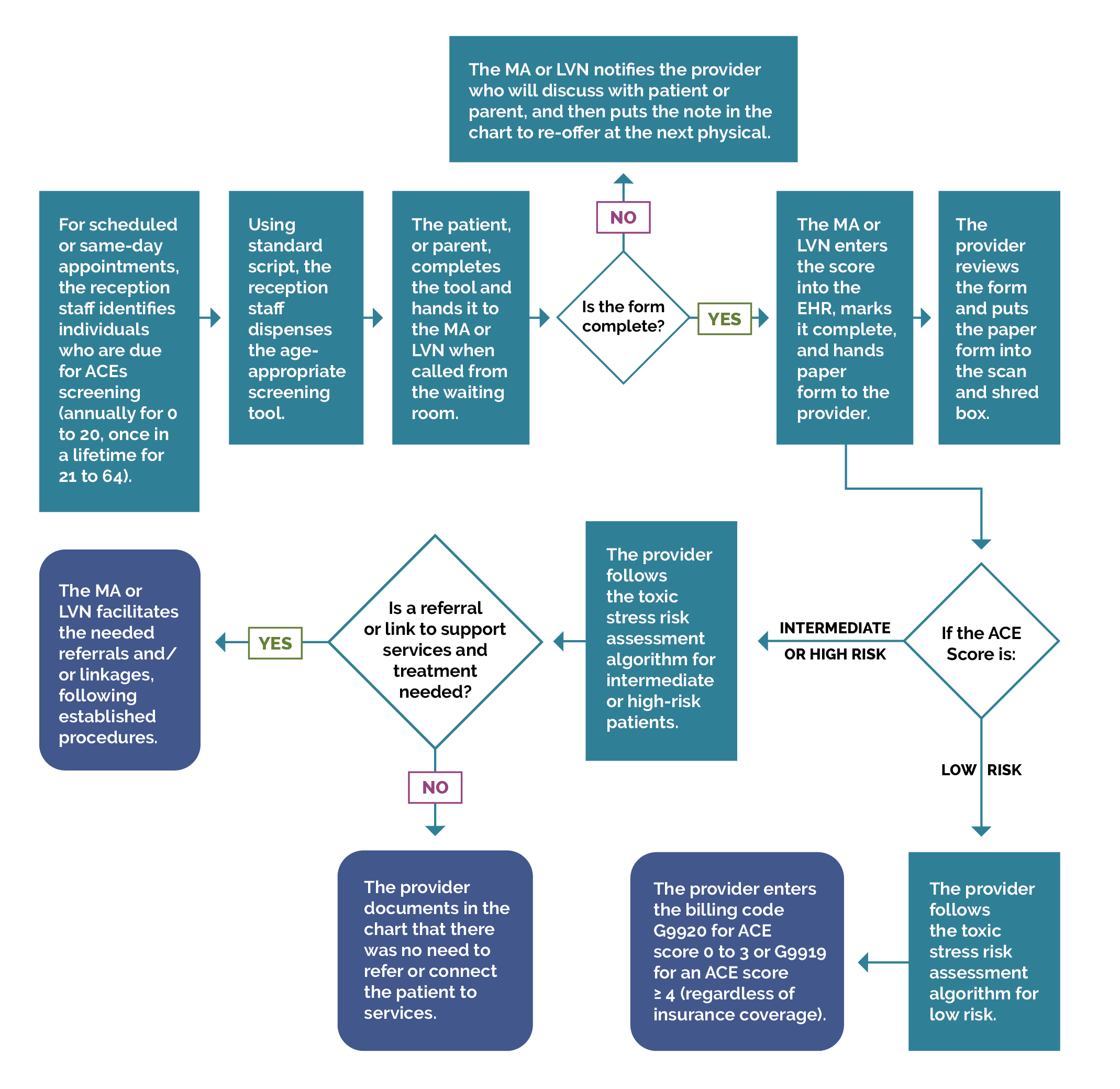

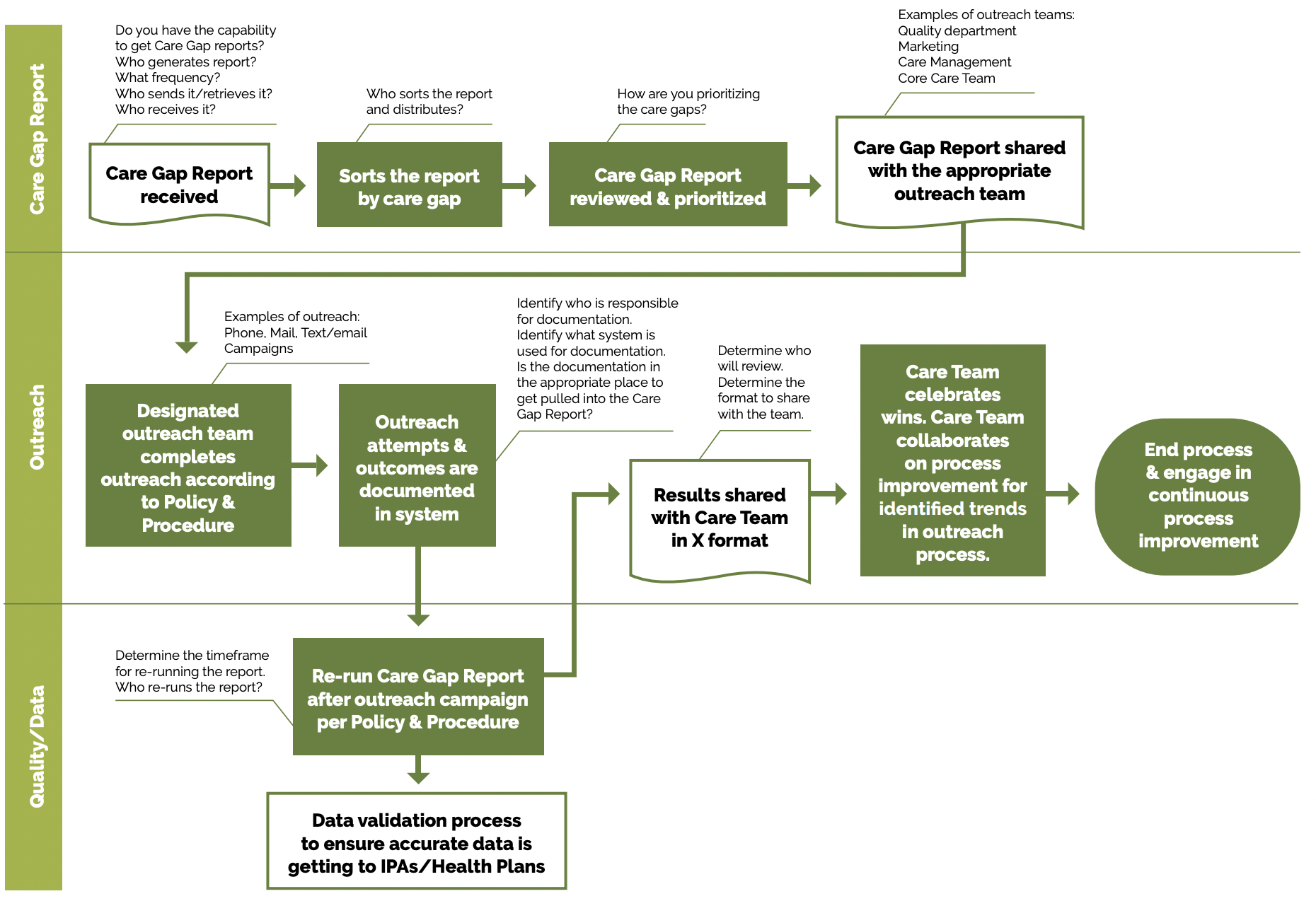

Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 provide an example of a care gap report for immunizations and well-child visits.

Other relevant HIT capabilities to support and relate to this activity include care guidelines, care dashboards and reports, quality reports, outreach and engagement, and care management and care coordination.

See Appendix D: Guidance on Technological Interventions.

Access to outside data may be a consideration or requirement (e.g., CAIR immunization data, school health data, and data from other practices) as services received outside the health center may be part of compliance. While claims data may be helpful in this regard, lag time may impact its usefulness. Patient-facing applications should be strongly considered to assure they are informed and appreciative of the nature and importance of recommended care. In California, many healthcare organizations are required or have chosen to participate the in California Data Exchange Framework (DxF), which can facilitate data sharing between clinics, MCPs and other partners.

FIGURE 4: EXAMPLE IMMUNIZATION CARE GAP REPORT FOR AN INDIVIDUAL PATIENT

FIGURE 5: EXAMPLE IMMUNIZATION CARE GAP REPORT FOR A PANEL OF PATIENTS UNDER TWO YEARS OF AGE

FIGURE 6: EXAMPLE WCV CARE GAP REPORT FOR A PANEL OF PATIENTS

Action steps and roles

1. Plan the care gap report.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Panel manager or data analyst. If it is not clear how the report can be produced, this step may involve one or more people from the practice who work on the EHR and, possibly, the EHR vendor.

As a team, decide what screenings or treatment guidelines are appropriate for your patients and prioritize the most important care gaps to run reports on. Start with the core and supplemental measures and any process measures your practice is tracking. Create care gap reports for childhood immunizations and recommended or standard well-child visits based on the Bright Futures periodicity schedule. Consider if there are any other gaps, clinical guidelines or measures your practice feels important to prioritize. See the Pre-Visit Planning: Leveraging the Team to Identify and Address Gaps in Care for a more complete list of preventive and health maintenance guidelines to consider.

Identify the inclusion criteria for each report, such as age, any exclusion criteria, and factors that make someone high risk.

For more information about California immunization requirements for school entry across childhood and adolescence, refer to Shots for School by the California Department of Public Health (CDPH). Initial efforts to develop care gap reports could focus on ensuring that pediatric patients are receiving these required immunizations.

Childhood immunizations are also tracked in the California Immunization Registry (CAIR). CAIR can link into your EHR to provide more up-to-date information for immunizations your patients received at community pharmacies or other health facilities. See Key Activity 2: Assess and Improve Reliability in Meeting Well-Child Visit (WCV) Recommendations for other tips on implementing these protocols.

2. Build the report.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Data analyst.

Determine whether the EHR has an existing report or one that can be modified to fit the inclusion criteria. You should talk to staff who are familiar with the electronic record; in some cases, it may be necessary to consult with the EHR vendor to confirm this information and how to run the report.

The care gap format should include:

- Criteria for inclusion in the report.

- The overall compliance rate for the care gap being measured.

- All patients eligible for the screening and their addresses and phone numbers.

- The last date the screening or service was provided (if known or if applicable), the previous results, and the type of assessment used.

- Preferred method of communication (e.g., phone, email, text).

Reports should be able to display and/or disaggregate the data based on:

- Race, ethnicity and language (REAL) as well as sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI).

- Any known social or behavioral needs.

- Communication preferences or other preferences that would inform the screening modalities offered, such as documented declination of prior screenings.

- Data on any other characteristic, including insufficient insurance coverage, that could pose a barrier to completing screening.

3. Standardize the data format.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Panel manager and care team.

Standardizing the data format and where it is entered is critical to ensuring accuracy in the resultant report. Once you know that a report can be produced, understand the specific data elements that are needed to produce the reports.

Document how each data element must be entered into the EHR in order to populate the fields needed for reporting. In some cases, data on completion of screening must be entered by hand (e.g., when the test is performed by a lab that does not communicate with the legacy EHR). Doing this will require a decision on the part of the practice as a whole and may require staff training and reinforcement on an ongoing basis. Where issues or apparent confusion are identified, regular discussion at team huddles or staff meetings will help in maintaining a standard approach.

Tip: Assign responsibility for the initial review of the reports to confirm data integrity.

4. Use the care gap reports in service to other workflows and improvement activities (e.g., assess and improve reliability in meeting well-child visit recommendations).

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Panel manager or data analyst.

A few examples include:

- At the patient level, the care gap report can be used for or linked with reminders or alerts for clinicians, as well as for sending reminders to patients who need to come into the clinic for screening or follow-up.

- Depending on communication preferences that have been expressed by patients, the patient care gap report may be exported to an automated reminder system that can trigger reminders by phone, text, email or mail.

- As part of the practice’s preplanning process, patient care gaps could be reviewed as part of the daily huddle. See Key Activity 5: Develop or Refine and Implement a Pre-visit Planning Process for more details.

FIGURE 7: EXAMPLE POPULATION CARE GAP REPORT ON IMMUNIZATION STATUS

5. Monitor the care gap report for accuracy and completeness.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Panel manager or data analyst.

It is critical to have bidirectional feedback with the practice’s care team about any real or potential errors in the care gap report, such as:

- Errors in how the data is entered compared to what is required under the new standardized data format.

- Patients who are eligible for and due for screening who are missing from the report.

- Patients who have recently been screened who are still listed as due for a screening.

Errors should be investigated through a chart review. If errors in the report specifications are discovered, the care gap report or process for producing the report should be modified. If the issue is incorrect documentation, staff training and reinforcement of documentation standards will be required.

Additional consideration for sustainability: Ensure there is an internal process for updating the criteria included in the EHR for care gap reports as clinical guidelines change.

Resources

KEY ACTIVITY #4:

Use a Systematic Approach to Decrease Inequities

This key activity involves all seven elements of person-centered population-based care: operationalize clinical guidelines; implement condition-specific registries; proactive patient outreach and engagement; pre-visit planning and care gap reduction; care coordination; behavioral health integration; address social needs.

Overview

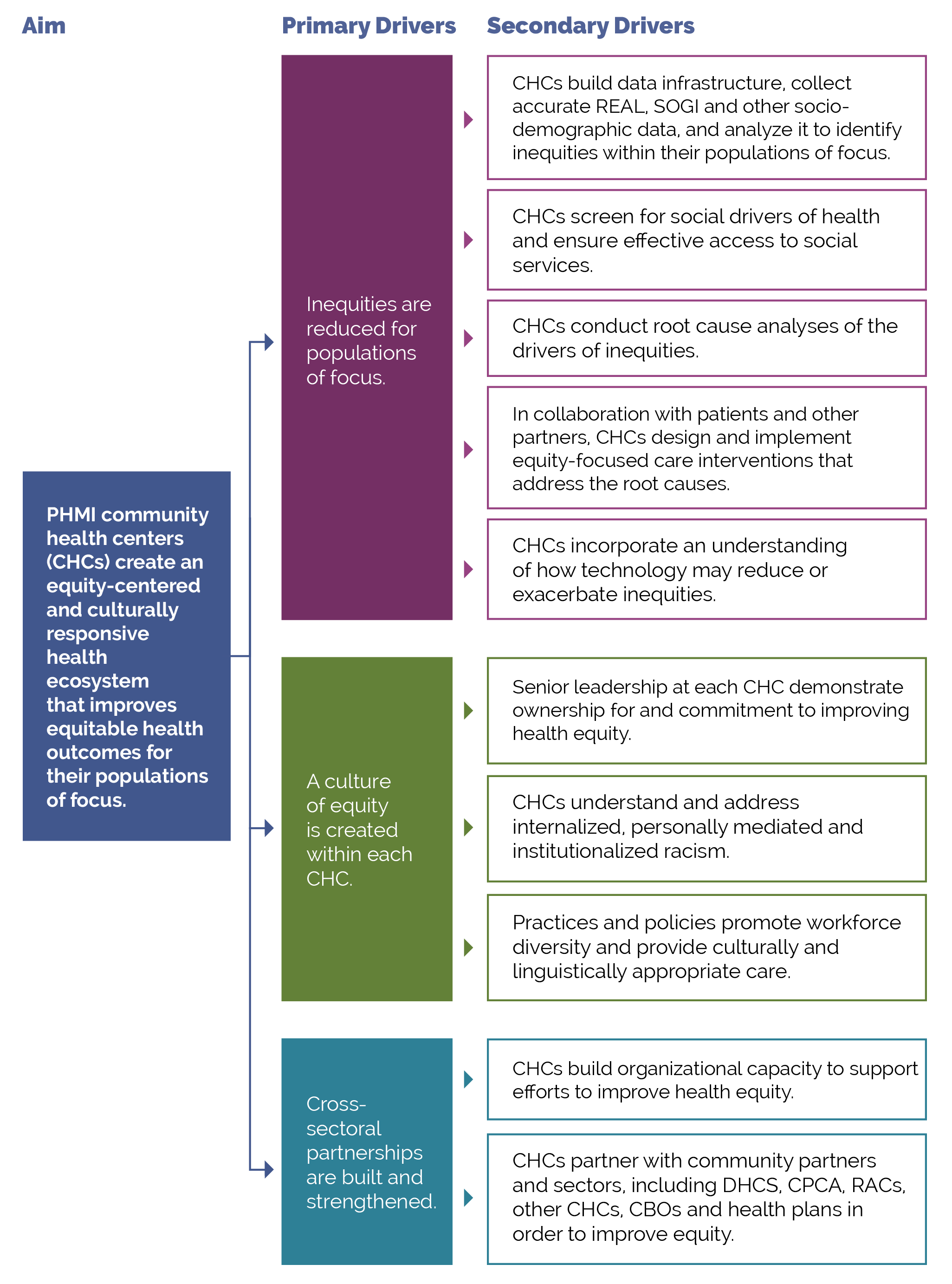

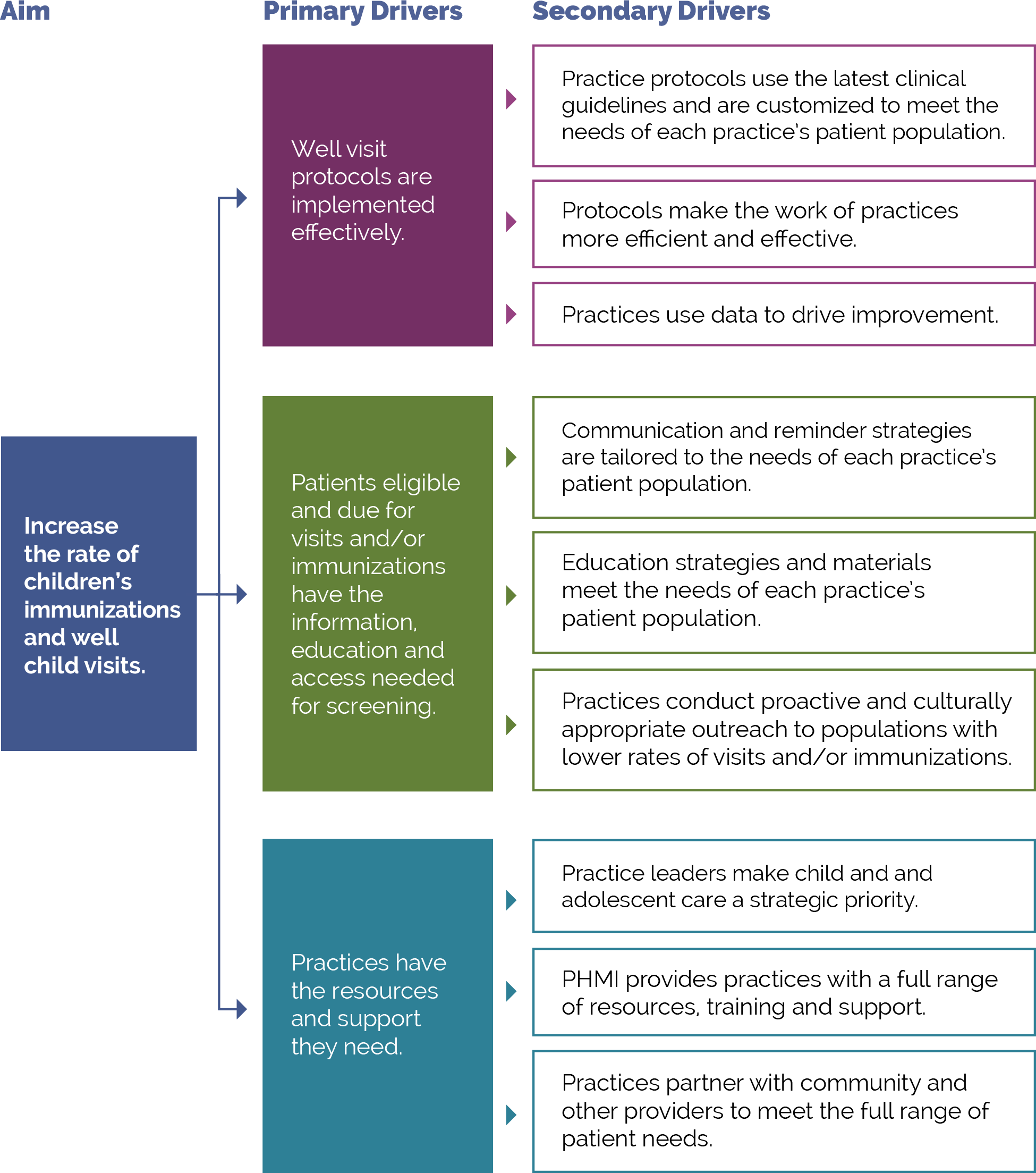

This activity provides guidance for a systematic evidence-based approach for identifying and then reducing inequities for children. It focuses on the first primary driver in PHMI’s equity approach: Reduce inequities for populations of focus.

FIGURE 8: PHMI EQUITY DRIVER DIAGRAM

As with virtually any clinical outcomes, your practice is likely achieving better outcomes with certain populations or subpopulations and worse outcomes with others. Inequitable outcomes are generally most acute among persons of color, immigrants, persons speaking a primary language other than English, and other populations who have been marginalized. As we work over time to reduce and eliminate inequitable health outcomes, we need to understand both what contributes to these different outcomes as well as factors that do not contribute to them.

This includes recognizing that race is a social construct determined by society’s perception. While some conditions are more common among people of certain heritage, disparities in conditions such as cancer, diabetes and adverse maternal outcomes have no genetic basis. While genetics do not play a role in these inequitable outcomes, the extent to which inequities in the quality of care received by people of color contribute to inequitable health outcomes has been extensively documented.[9] These inequities are often a direct result of racism, particularly institutionalized racism – that is, the differential access to the goods, services and opportunities of a society by race.[10] Racial health inequities are evidence that the social categories of race and ethnicity have biological consequences due to the impact of racism and social inequality on people’s health.[11] It is also critical to recognize that we have policies, systems and procedures that unintentionally cause inequitable outcomes for racial, ethnic, language and other minorities, in spite of our genuine intentions to provide equitable care and produce equitable health outcomes.

Improving your practice’s key outcomes for children requires a systematic approach to identifying equity gaps (e.g., who your practice is not yet achieving equitable outcomes for) and then using quality improvement (QI), collaboratively design, systems thinking and related methods to reduce these equity gaps. This effort will be more effective if it is guided by a theory of change that addresses the ways in which structural and institutional racism lead to inequities in care provision. For more discussion, read resources such as this one from the Center for American Progress on how structural and institutional racism contributes to declining childhood immunizations rates.

Identifying and meeting patients’ social health needs is a key driver of reducing inequitable health outcomes. We provide additional guidance in this key activity on how to both reduce inequities and meet patients’ social health needs.

Access to data required to identify and monitor inequities as outlined in the key actions outlined below is fundamental to this activity.

Relevant HIT capabilities to support this activity include care guidelines, registries, clinical decision support (modifications required to consider disparate groups), care dashboards and reports, quality reports, outreach and engagement, and care management and care coordination (See Appendix D: Guidance on Technological Interventions).

EHRs have the ability to capture basic underlying socioeconomic, SOGI and social needs-related data but may in some cases lack granularity or nuances that may be important for subpopulations. Mismatches between how UDS captures REAL data versus how EHRs capture or MCPs report data can also create challenges. This may require using workarounds to capture these details. It is also important to assure that other applications in use, which may have separate patient registration processes, are aligned. Furthermore, tracking inequities in accessing services not provided by the health center may also require attention to data sources or applications outside the EHR.

In the pediatric population, some of the contributing data may pertain to the parent or caregiver. For example, children’s risk of experiencing chronic disease is associated with maternal health conditions including asthma, obesity and mental distress.[12] Where possible and relevant, comprehensive strategies might include ability to draw such data into analyses and reports.

Health centers should also be alert to the potential for technology as a contributor to inequities. For example, patient access to telehealth services from your practice may be limited by the inequitable distribution of broadband networks and patient financial resources (e.g., for phones, tablets, and cellular data plans). EHR-embedded algorithms used to stratify populations by risk may also contain inherent racial biases. The Techquity framework can be a useful way to structure an approach to assure that technology promotes rather than exacerbates disparity.

Language, literacy levels, technology access and technology literacy should also be considered and assessed against the populations served at the health center.

Finally, attention needs to be paid to the use of best practices in collecting the data, accurate categories in the technologies in which it is collected and stored, and adequate training and monitoring of staff responsible in order to assure reports and analysis have a valid basis.

Action steps and roles

1. Build the data infrastructure needed to accurately collect REAL, SOGI and other demographic data.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Data analyst.

The PHMI Data Quality and Reporting Guide provides guidance and several resources for collecting this information. According to this guide, the initial step in addressing disparities is to collect high-quality data that fosters a comprehensive understanding of each patient. This entails incorporating race, ethnicity and language (REAL) data, demographic data (age, gender) and social needs data. By leveraging this information, healthcare practices can gain valuable insights into disparities in access, continuity and health outcomes." Steps two to four below provide more information on this process.

Collecting REAL information allows for practices to identify and measure disparities in care, while also ensuring that practices are able to interact successfully with patients. This is done by understanding their unique culture and language preferences.[13] KHA Quality has a toolbox that assists with REAL data collection.

The Uniform Data System (UDS) Health Center Data Reporting Guidance (2023 Manual) provides detailed guidance on REAL and sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI). Note: While UDS does not currently require that practices report on the specific primary language of each patient, practices should make an effort to identify and record each patient’s primary language, as UDS reporting still requires for languages other than English to be reported.

Accurate collection of data requires appropriate fields and options in the EHR and other employed technologies, as well as appropriate human workflows in collecting the data. Staff responsible for data collection should be continuously trained and assessed for best practices in data collection, including promotion of patient self-report.

In addition, practices should work to ensure that patients understand the importance and use of this information to help them feel comfortable supporting its collection. Example language can be found at The MGH Disparities Solution Center. High rates of “undetermined” or “declined” in these fields may be indicative of the need to attend to these staff training needs.

Collecting this data is important, especially to obtain a complete picture of health for patients who identify as transgender. There are certain risks and condition indicators that are gender-specific, which impact how care teams provide care to a patient. By understanding the needs of patients more fully, care teams can make more informed decisions for the best treatment of their patients. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) has provided further guidance regarding standards of care related to gender diversity.

2. Use the practice’s EHR and/or population health management tool to understand inequitable health outcomes at your practice by stratifying your data.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Data analyst.

This includes reviewing your care gap report or care registry and being able to stratify all of the following:

- Core measures for the population of focus.

- Supplemental measures for the population of focus.

- Process measures for the population of focus.

Stratify this data by:

- Race, ethnicity and language (REAL).

- Sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI), when possible.

- Other factors that can help identify subpopulations in need of focused intervention to reduce an equity gap (e.g., immigrants, people experiencing homelessness, etc.).

This is not a one-time event, but rather a continuous process (see step 13 below) and should be done in tandem with step three below.

Consider reviewing data on disparities at the state and health plan level for greater context.

You might not have enough sample size in some REAL categories to identify whether a trend is significant or not. If you’re seeing something in your patient population, you can examine other known data sources, such as a recent state health disparities report, for context.

3. Screen patients for social needs.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Care team.

Key Activity 7A: Develop a Screening Process for Social Needs and Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACESs) that Informs Patient Treatment Plans provides guidance on screening patients for health-related social needs and how the information can begin to be used to inform patient treatment plans, including referral to community-based services. This is not a one-time event, but rather a continuous process and should be done in tandem with step two above.

4. Analyze the stratified data from steps two and three to identify patterns of inequitable outcomes.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Data analyst, QI leads, care team.

Analyze the stratified data from steps two and three to identify patterns in inequitable outcomes.

This includes:

- Utilizing tools to examine, visualize and understand disparities across different populations or subpopulations.

- Data over time (using run charts).

- Exploring trends, patterns and significant differences to understand which demographic groups will require a focused effort to close equity gaps.

Update your practice’s measurement strategy so your practice’s improvement efforts remain centered around advancing equitable outcomes. Some examples include creating specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, time-bound, inclusive and equitable (SMARTIE) goals and updating your process and outcome measures so you can understand differences by REAL or SOGI indicators. See Appendix C: Developing a Robust Measurement Strategy for more.

This is not a one-time event but rather a continuous process (see step 13 below). Periodic review of stratified data allows for recognition of gap closures and emergence of new disparities.

5. Use a root cause analysis to identify improvement approaches for subpopulations with lagging health outcomes.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Implementation team.

Select root cause analysis approaches that work best for the equity gap you are closing:

- Engage and gather information from patients affected by the health outcome in your root cause analysis (see step six).

- Brainstorming.

- Systems thinking (understanding how interconnected social, economic, cultural and healthcare access factors may be impacting the health outcome).

- Tools that rank root causes by their impact and the feasibility of addressing them (e.g., prioritization matrix and/or an impact effort matrix).

- Visual mapping of root causes and effects (e.g., fishbone diagram).

- Perform focused investigations into selected root causes, gathering qualitative data through interviews, surveys or focus groups with the subpopulation of focus.

Present the findings to a broader group of stakeholders to validate the identified root causes and gain additional insights. Incorporate their feedback and refine the analysis, as needed.

6. Partner with patients to build successful strategies addressing inequitable outcomes.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Care team and people with lived experience (patients representative of the population(s) of focus).

Using one or more human-centered design methods, such as focus groups, Journey Mapping, etc. (see links to these methods below), and engage patients to better understand perspectives that may influence the health outcome of interest. This may include collecting information on:

- Their assets, needs and preferences.

- Cultural beliefs, including traditional healing practices.

- Level of trust in healthcare generally and in the topic of focus specifically (e.g., immunizations, behavioral health, etc.).

- Barriers to accessing care.

- Barriers to remaining engaged in care.

- Trusted sources of information or communication mechanisms for this population.

- Their ideas for improving health outcomes.

The patients you partner with for this and other steps in this key activity may be part of a formal or informal patient group and/or identified and engaged specifically for this equity work. Fairly compensating patients for participating in improvement activities is a best practice.

Selected resources on human-centered design and collaboratively design:

- Center for Care Innovations (CCI) Human Centered Design Curriculum via CCI Academy.

- IDEO’s Field Guide to Human-Centered Design.

- IDEO’s Design Kit: Methods.

7. Develop strategies that address or partially address the identified equity gaps.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Care team and people with lived experience.

Based upon the insights your practice has developed for a population of focus and your root cause analysis, determine which of the key activities this guide could address or partially address the equity gap.

Most of the activities in this guide either explicitly address an equity challenge or can be adapted to better address an equity challenge. Examples of activities that can be adapted to reduce identified equity gaps include but are not limited to:

- Key Activity 9: Proactively Reach Out to Patients Due for Care.

- Key Activity 7A: Develop a Screening Process for Social Needs and Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) that Informs Patient Treatment Plans, such as providing a referral for one of the Medi-Cal Community Supports.

- Key Activity 11: Coordinate Care.

- Key Activity 15: Strengthen Community Partnerships.

If one or more of your root causes cannot be addressed fully through key activities in the relevant implementation guide, use one or more human-centered design methods to develop ideas to improve health outcomes and reduce inequities among this population.

Developing these ideas is best done with representatives of the population of focus, as they have expertise and experience that may be missing from the practice's care team. During this brainstorm, you are developing ideas without immediate judgment of the ideas in an effort to generate dozens of potentially viable strategies.

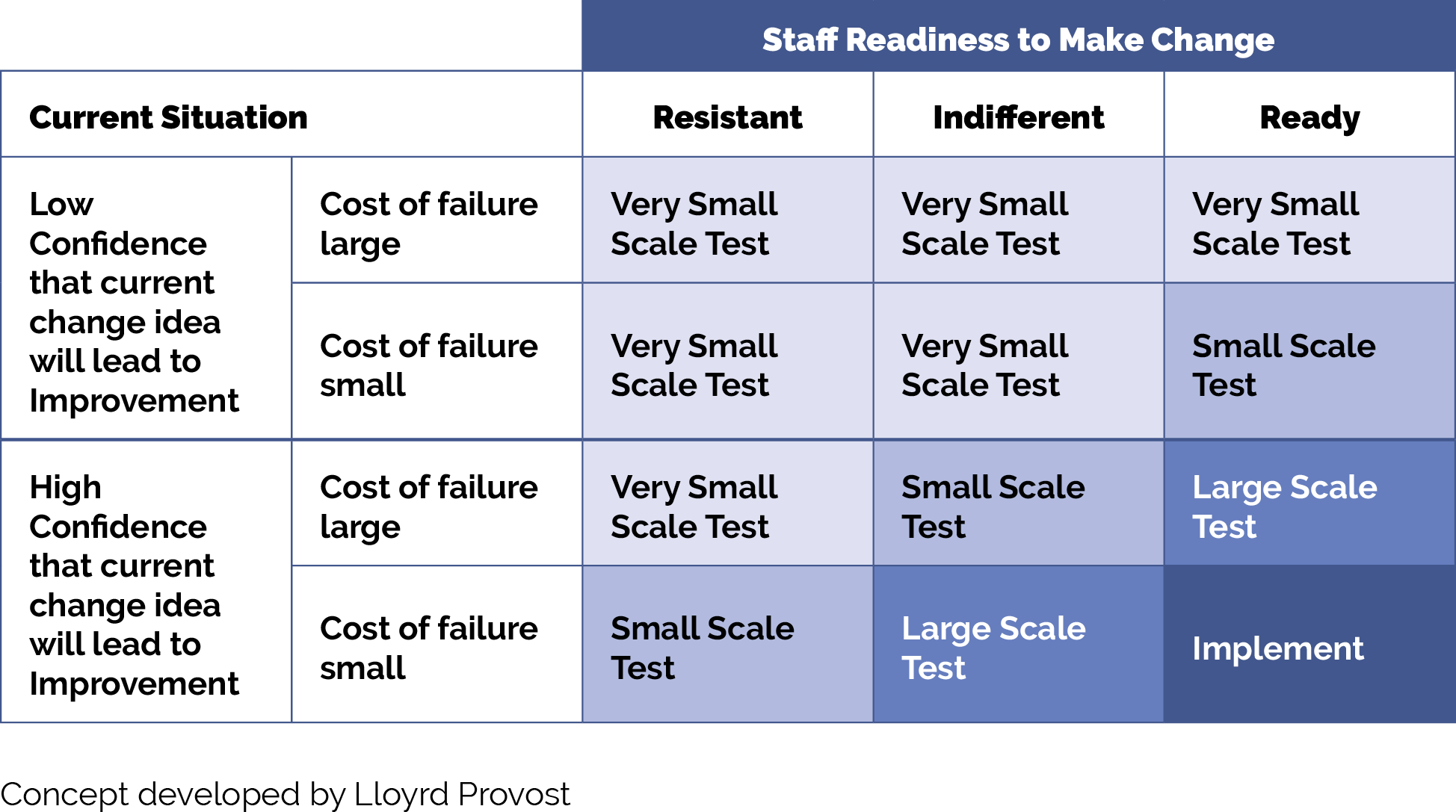

8. Determine which strategies to test first.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Care team and people with lived experience.

There are many ways to prioritize ideas. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) often recommends a prioritization matrix and/or an impact effort matrix and offers a video on making them.

If you have organized your key activities and new ideas into themes or categories, you may choose to work on one category or select one or two ideas per category to work on.

The number of key activities and/or new ideas that you prioritize for testing first should be based on the team’s bandwidth to engage in testing. It is critical to determine the bandwidth for the team(s) who will be doing the testing so that you can determine how many ideas to test first.

9. Use quality improvement (QI) methods to begin testing your prioritized key activities and new ideas.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Care team and people with lived experience.

Nearly all the key activities and all of your new ideas will require some degree of adaptation for use within your practice and to be culturally relevant and appropriate to your patient population.

Use plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles, generally starting as small as feasible. Think “ones” (e.g., one clinician, one hour, one patient, etc.) and become larger as your degree of confidence in the intervention grows.

Whenever testing a key activity or new idea, we recommend that the practice:

- Use plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles to test your ideas and bring them to scale. See more information on PDSAs below in the tips and resources section.

- Generally, start with smaller scale tests (e.g., test with one patient, for one afternoon, in a mailing to 10 patients, etc.). Use the chart titled “How Big Should My Test Be?” below in the tips and resources section to help you decide what size test is most appropriate.

Develop or refine your learning and measurement system for the ideas you are testing. A simple yet robust learning and measurement system will help you understand improvements, unintended secondary effects, and how implementation is going.

By working out the inevitable challenges in the idea you are testing using a smaller scale PDSA cycle, the improvement activity will ultimately work better for patients and be less frustrating to the care team. Testing and refining also can eliminate inefficient workarounds that occur when a new process or approach is imposed onto an existing system or workflow.

Select resources on quality improvement (QI):

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s (IHI) QI Essentials Toolkit, including details on:

- Cause and effect diagrams.

- Driver diagrams.

- Failure modes and effects analysis.

- Flowcharts.

- Histograms.

- Pareto charts.

- PDSA worksheet.

- Project planning forms.

- Run charts.

- Scatter diagrams.

- IHI’s Videos on the Model for Improvement (Part one and Part two).

- Rapid Experiments to Improve Healthcare Delivery.

- CCI’s ABC's of QI via CCI Academy.

10. Implement – bring to full scale and sustain – those practices that have proven effective.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Care team.

Once an idea has been well tested and shown to be effective, it is time for your practice to hardwire the idea, approach or practice into your daily work. Consider using the MOCHA Implementation Planning Worksheet to think through:

- Measurement.

- Ownership.

- Communication (including training).

- Hardwiring the practice.

- Assessment of workload.

Sometimes implementation may require that you update your protocol and/or policies and procedures for the populations of focus.

11. Once you have tested, refined and scaled up the initially prioritized ideas, begin testing other ideas.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Care team and people with lived experience.

This might include going back to the ideas developed previously but not prioritized and/or going back through the testing steps above to develop and prioritize new ideas and potentially for additional populations of focus.

12. Put in place formal and informal feedback loops with patients and the care team.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Care team.

Establishing formal and informal feedback loops regarding new processes will ensure that your practice’s ideas are meeting the needs of patients and are reducing identified equity gaps. These feedback loops also ensure the changes are feasible and sustainable for your practice.

For patients, feedback loops could be created using many of the human-centered design tools used to design your improvement activity (e.g., surveys, interviews, focus groups). Feedback loops should also involve the patient satisfaction survey and grievance processes. Consider establishing a standing funded patient advisory board that is available to design, implement and evaluate all of your practice’s improvement activities.

For the care team, feedback loops might include:

- Existing or new staff satisfaction and feedback mechanisms.

- Regularly scheduled meetings and calls to obtain staff feedback on processes, methods and tools. Leverage existing meetings to mitigate staff burnout.

13. Continually analyze your data to determine if your efforts are closing equity gaps.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Care team.

This includes regular (at least monthly) review of the key stratified measures from your measurement strategy. Share the data with patients to both show your work to decrease known equity gaps and to solicit ideas for closing them.

Implementation tips

- When testing a change idea (either a key activity or new idea) for your practice to address a known equity gap, the size of your test scope or group is critical.

- We recommend starting with a very small test (e.g., with one patient or with one clinician) or a small test (e.g., with all patients seen during a three-hour period by this clinician) unless you are certain the change idea, key activity or test will lead to improvement with little or no adaptation for your practice, the cost of a failed test is extremely low, and staff are excited to test the change idea.

- As you learn from each test what is and isn’t working, you can conduct larger scale tests and tests under a variety of conditions. While at first glance this would appear to slow down the implementation effort, starting small and working out the kinks as you progressively work to full scale actually saves time and resources and is much less frustrating for your patients and care team. The visualization below provides guidance on how big your test should be.

FIGURE 9: HOW BIG SHOULD MY TEST BE?

Resources

KEY ACTIVITY #5:

Develop or Refine and Implement a Pre-Visit Planning Process

This key activity involves all seven elements of person-centered population-based care: operationalize clinical guidelines; pre-visit planning and care gap reduction; care coordination; address social needs.

Overview

This key activity provides guidance for how the care team can effectively and efficiently embed preventive care measures into the practice’s pre-visit planning process (PVP). Pre-visit planning is typically driven by the medical assistant with help from other care team members and includes steps taken:

- At the end of the current visit to ensure the patient understands any actions they need to take and to schedule for any follow-up.

- Prior to a scheduled appointment, to scrub the chart and identify any pre-visit tasks per the pre-visit checklist.

- The day of an appointment, during the daily huddle and before the patient sees the PCP.

Approximately 80% of pediatric visits last 20 minutes or less,[14] and many patients come to these visits with multiple needs. Pre-visit planning works towards optimizing a team-based approach outside of these short primary care visits so patients receive comprehensive care in alignment with the latest clinical guidelines and their own preferences.

Pre-visit planning allows for better coordination of care. This can be particularly beneficial for patients with complex health needs, ensuring they receive comprehensive and equitable care. As your practice works to reduce any identified equity gaps, pre-visit planning is often a powerful activity for ensuring culturally relevant care as the care team partners with the patient to discuss follow-up actions.

The PVP should incorporate your practice’s process for screening and responding to social needs, including checking whether social needs screening is due. When social needs are identified the team should be clear on the pathways, both during and after visits, to address and follow up on those needs.

Pre-visit planning draws upon similar technical enablers as care gap reporting, and likewise can be facilitated at the individual patient level and at the level of groups of patients coming for care by a specific team in an appointment schedule block. The format in which planning is done needs to consider the workflow and staffing model.