©️ 2024 Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, Inc.

This guide provides step-by-step guidance for improving population-based care for adults with preventive care needs with the goal of supporting substantive cultural, technological and process changes. In particular, it focuses on increasing screening rates for colorectal cancer, breast cancer and cervical cancer.

This guide was designed as part of the Population Health Management Initiative (PHMI), a California collaboration of the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS), Kaiser Permanente and Community Health Centers. Much of the content is relevant and adaptable to primary care practices of all kinds working to improve the health of the populations they serve.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in 2020[1] colorectal cancer, female breast cancer and cervical cancer resulted in over 98,000 deaths in the U.S. and over 10,000 deaths in California.

|

Cancer Type |

Location |

New Cases 2020 |

Deaths 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

Colorectal cancer |

United States |

126,240 |

51,869 |

California |

13,447 |

5,401 |

|

Female breast cancer |

United States |

239,612 |

42,273 |

California |

25,809 |

4,520 |

|

Adults living with chronic conditions |

United States |

11,542 |

4,272 |

California |

1,346 |

489 |

One of our more powerful tools in the fight against these three cancers is having all patients complete all the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force’s (USPSTF) recommended screenings. Despite the known benefits of screening, screening rates for these three cancers are suboptimal.[2]

|

Cancer Screening Type |

California Screening Rate |

National Rank |

U.S. Screening Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

Up-to-date stool test, endoscopy and colonoscopy; 45 to 75 years; 2020 |

53% |

52 |

64% |

Up-to-date mammography; people 40 to 74 years; 2020* |

60% |

49 |

67% |

Up-to-date Pap smear and human papillomavirus (HPV) test; people 21 to 65 years; 2020* |

87% |

25 |

87% |

*The USPSTF is currently in the process of updating these guidelines, and clinical teams should review progress in order to incorporate current guidance.

Developing, implementing and continually improving a multifaceted and culturally relevant cancer screening protocol that includes all patients is critically important for a range of reasons:

- It helps avoid missed or delayed diagnosis, which is devastating to patients and their family and caregivers.

- A culturally relevant screening program can help to address inequities in access and outcomes by tailoring outreach and education to the populations served by your practice.

- It helps practices adhere to the most current cancer screening guidelines.

The work to ensure that all adults receive all recommended cancer screenings is a continuous effort and we still have much to learn. This living document uses existing evidence, bright spots and examples from the field to offer practical guidance on improving the effectiveness of your cancer screening protocols. While some of the guidance in this document is technical, much of the guide is focused on supporting practices in the substantive cultural, technological and process changes that lead to improved population-based care for adults. Virtually every activity in the guide will require some level of adaptation for your practice’s unique context. Population Health Management Initiative (PHMI) will update this guide as we learn from and with practices.

We have organized the key activities in this guide into three categories:

- Foundational activities: Activities that all practices should implement as part of their cancer screening protocol.

- Going deeper activities: More advanced activities that build off the key activities and that help to ensure your practice can achieve equitable improvement in your cancer screening rates.

- On the horizon activities: Additional activities, including ideas worthy of testing that include the latest ideas and thinking on cancer screening.

Sequencing activities: We recommend that practices consider planning and attempting to implement the activities in the sequence provided in this guide. At the same time, we recognize that different practices may follow a different path toward prioritizing and implementing these activities. Furthermore, there is overlap between activities; many activities build off or from the building blocks of other activities.

Testing and implementing: For each activity, we provide guidance on how to plan, test and implement the activity along with links to other resources, technology considerations and examples. Consider testing different versions of the action steps and roles on a small scale before fully implementing at your practice.

Maintaining the progress: For many activities we have also provided tips for periodically reviewing and making improvements to key workflows even after initially implementing the change. Ongoing review and continual improvement are important for your practice to maintain your progress in population health management and help you stay nimble in adapting to changing patient demographics, new clinical best practices, new payment policies, workforce changes and other changes at your practice.

If your practice implements the foundational activities in this guide, you should be able to achieve the following key competencies.For adult preventive care your practice will be able to consistently:

- Engage patients served by your practice to validate any of your proposed process improvements and to propose alternative methods to improve quality in your focus area.

- Analyze core quality measures to identify inequities and improvement opportunities for colorectal, breast and cervical screening rates.

- Use evidence-based clinical guidelines, identify when and where it is necessary to update, or develop new protocol(s) for colorectal, breast and cervical screening.

- Create an outreach protocol to reach and engage all attributed patients.

- Create a health-related social needs screening process that informs patients’ treatment plans.

- Assess current health information technology (HIT) capabilities and develop a plan for ongoing improvement in data utilization, care team workflows, and efficiency.

This guide also includes sections on measurement, equity, social health and behavioral health integration and an appendix including helpful tools and resources. We have included information about California Medi-Cal-covered benefits and services that were up to date at the time of publishing, but benefits and billing guidance change over time. Nothing in this guide should be considered formal guidance, and anyone using this guide should check with the appropriate authorities on benefits and billing guidance. This document will be refined based on continued learning on this topic and may include additional activities, examples, resources and sections in the future.

Improving the health of a population impacts everyone in a practice. Critical roles needed to engage in the work outlined in this guide and support practice change include:

- Quality improvement leadership, like a director of quality improvement (QI), to support cultural changes.

- Coaches or practice facilitators who are partnered with teams to help identify areas for improvement and support change through change management strategies.

Putting the Key Activities in Context

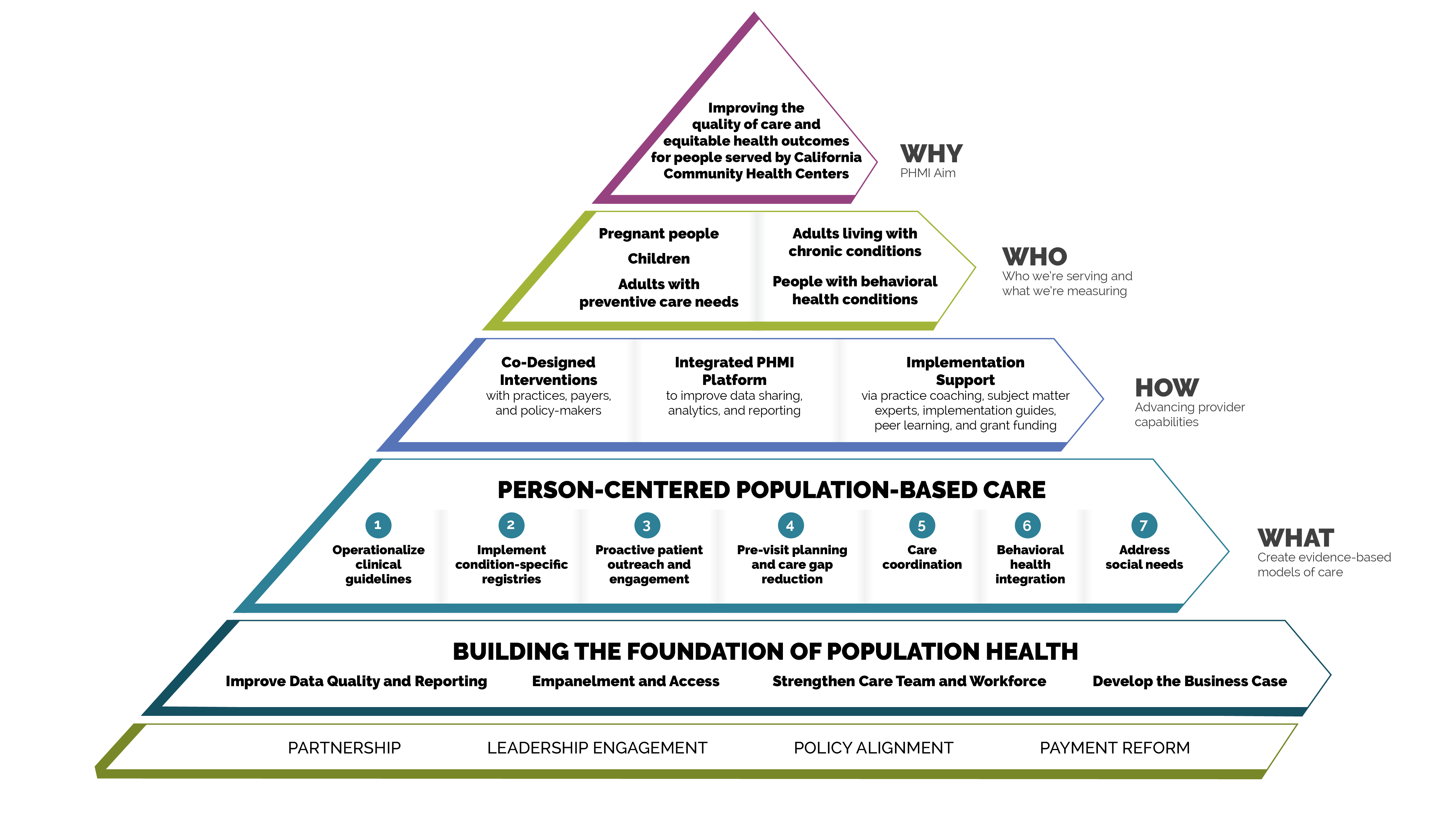

Person-centered population-based care

Each of the key activities advance one or more of the seven person-centered population-based care change concepts:

- Operationalize clinical guidelines.

- Implement condition-specific registries.

- Proactive patient outreach and engagement.

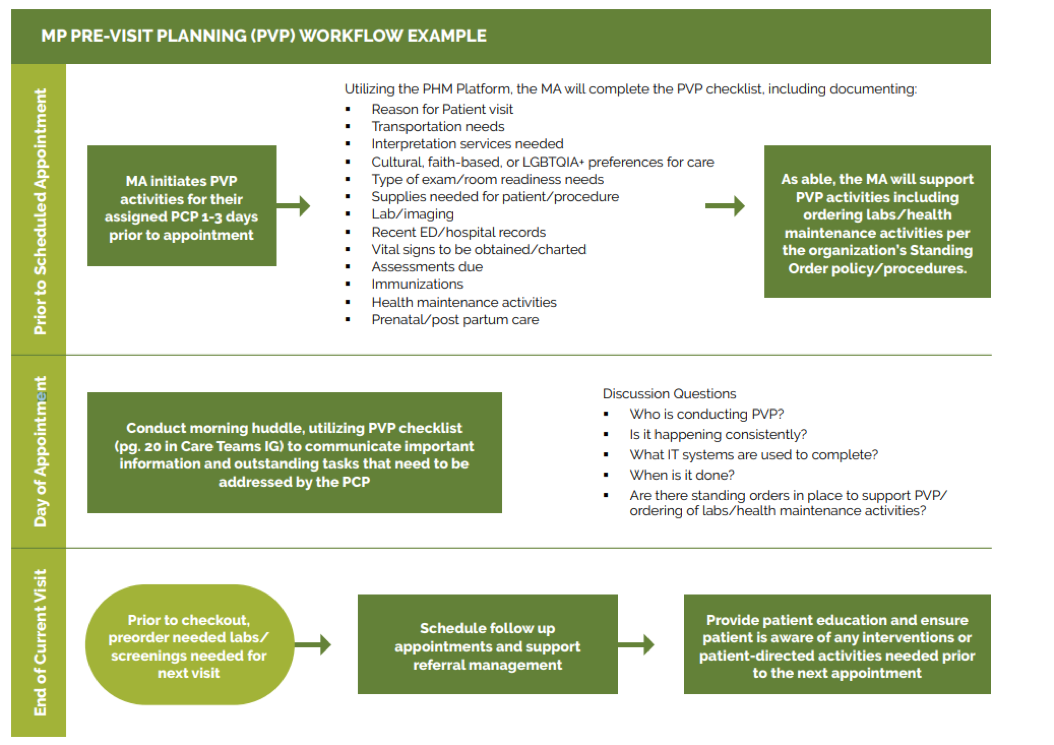

- Pre-visit planning and care gap reduction.

- Care coordination.

- Behavioral health integration.

- Address social needs.

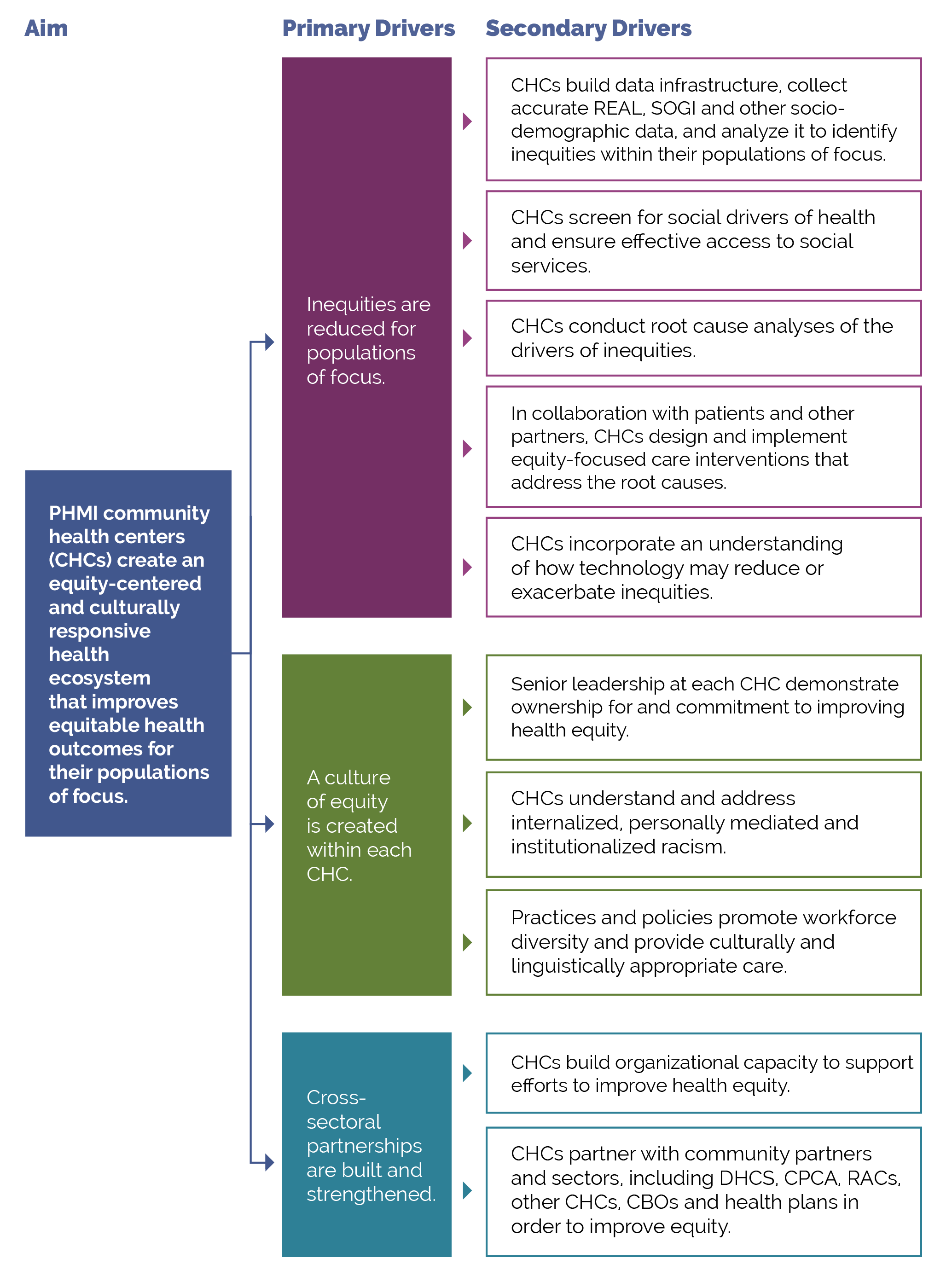

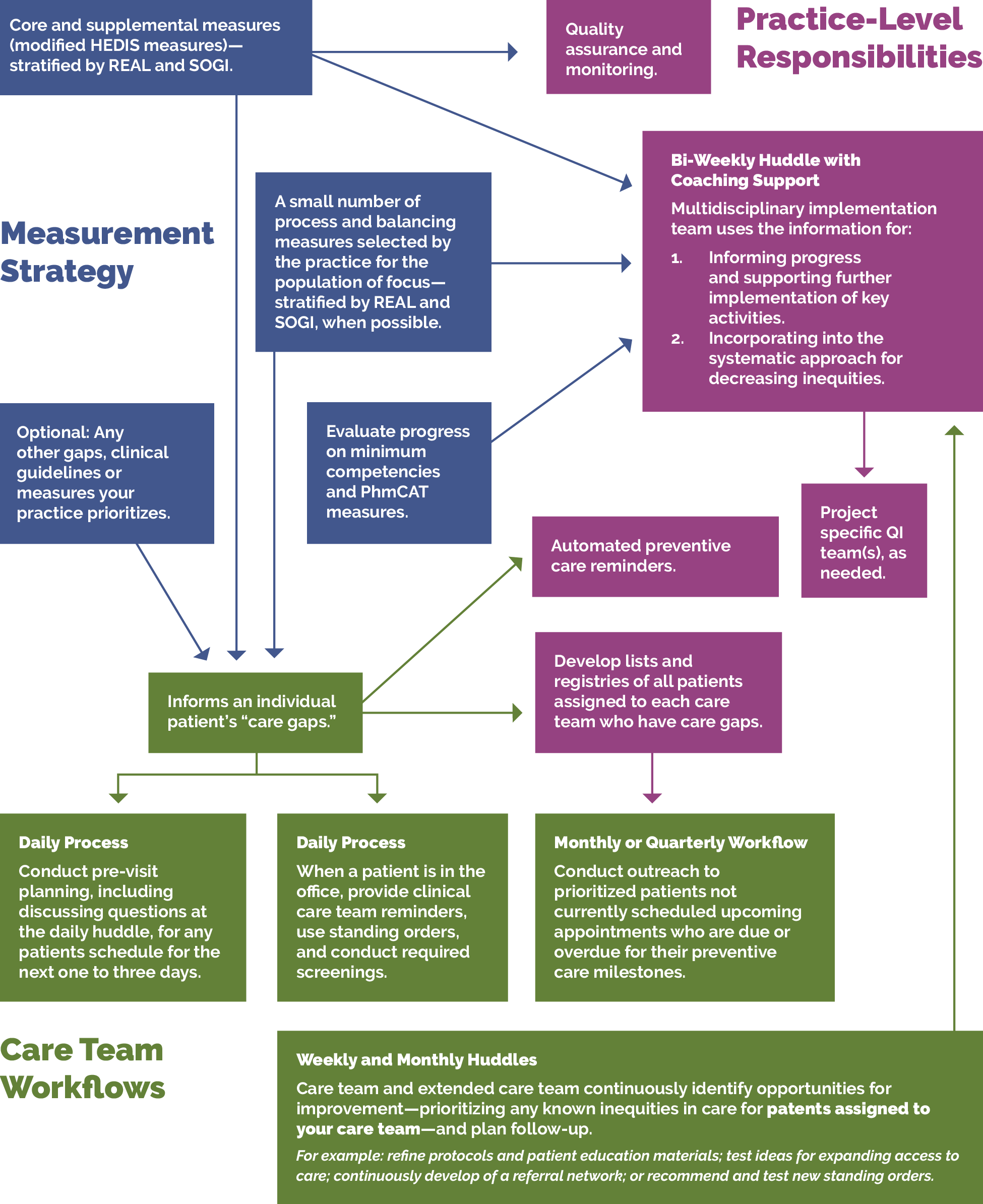

FIGURE 1: PHMI IMPLEMENTATION MODEL

The measures covered in this guide consist of Healthcare Effective Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures designated as core and supplemental measures by PHMI. These measures can be considered outcome measures because there is ample evidence that improved timely care will improve overall population health outcomes for adults requiring cancer screening. All measures use standard HEDIS definitions and are aligned with California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Cal (CalAIM) and Alternative Payment Methodology (APM) 2.0. For information about these measures, reference the PHMI Data Quality and Reporting Guide.

PHMI has selected one core and two supplemental measures of focus for adults with preventive care needs. Practices can track other measures that feel important and relevant. This guide provides detailed guidance to improve your practice’s results on the following four core and supplemental measures:

- Colorectal Cancer Screening (Core Measure).

- Breast Cancer Screening (Supplemental Measure).

- Cervical Cancer Screening (Supplemental Measure).

Core HEDIS measures for PHMI

|

PHMI Populations of Focus |

Measures |

|---|---|

Adults with preventive care needs |

Colorectal Cancer Screening |

Supplemental HEDIS measures for PHMI

|

PHMI Populations of Focus |

Measures |

|---|---|

Adults with preventive care needs |

Breast Cancer Screening |

|

Cervical Cancer Screening

|

The core and supplemental measures are part of a larger measurement strategy and learning system, as outlined in Appendix A: Sample, Idealized System Diagram: Weaving Your Measurement Strategy and Learning System into Practice Operations. Key Activity 1: Convening a Multidisciplinary Implementation Team for Cancer Screening outlines how your practice can develop a robust measurement system to support this work. In addition to quality assurance and monitoring, measures are also used during practice operations alongside other data for learning to:

- Guide the actions of the multidisciplinary implementation team as they use a systematic approach to decreasing inequities and implementing key activities across the practice.

- Support the care team’s efforts to advance population health and reduce care gaps through daily, weekly and monthly workflows, as well as continuous identification of opportunities for improvement.

The PHMI Clinical Guidelines Advisory Group (CGAG) was established to create a standardized approach to review, adopt and promote established clinical guidelines in the PHMI cohort. For more information, please see the PHMI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Key Medi-Cal Populations of Focus.

Colorectal cancer screening clinical guidelines

FIGURE 2: CLINICAL GUIDELINES: COLORECTAL CANCER SCREENING

Guideline source |

|

PHMI measure |

Colorectal Cancer Screening |

Guideline language |

Conduct colorectal cancer screening for persons aged 45 to 75 using any of the following screening modalities and intervals:

|

Breast cancer screening clinical guidelines

FIGURE 3: CLINICAL GUIDELINES: BREAST CANCER SCREENING

Guideline Source |

|

PHMI Measure |

Breast Cancer Screening |

Guideline Language |

Age to start Mammography (USPSTF): Biennial screening mammography is recommended for women aged 40 y/o. The decision to start screening mammography in women prior to age 40 y/o should be an individual one. |

Cervical cancer screening clinical guidelines

FIGURE 4: CLINICAL GUIDELINES: CERVICAL CANCER SCREENING

Guideline Source |

|

PHMI Measure |

Cervical Cancer Screening |

Guideline Language |

Age 21-65 (USPSTF):

No Testing (USPSTF):

|

Many key activities in this guide include considerations for utilizing the intervention to improve equitable health outcomes and reduce the effects of racism, bias and discrimination. Key Activity 4: Use a Systematic Approach to Address Inequities within the Population of Focus describes key action steps for how to make an intentional and explicit effort to identify inequities, understand root causes and reduce those inequities.

This guide also offers resources for going deeper into organizational and ecosystem-level work to advance equitable outcomes through Key Activity 18: Strengthen a Culture of Equity. More information about this approach can be found in the PHMI Equity Framework and Approach.

Integrated behavioral health supports are important for adults, as behavioral health support is likely to boost health outcomes and enhance patients' quality of life. One foundational change is to ensure that the care team includes behavioral health staff as core members of the team; this is covered in detail in the Care Teams and Workforce Guide.

We also offer a resource, Pre-Visit Planning: Leveraging the Team to Identify and Address Gaps in Care, that includes recommended behavioral health screenings.

Throughout the key activities in this guide, we have incorporated considerations for providing trauma-informed care in the approach to cancer screening. Trauma is recognized as a potential barrier to seeking or engaging in cancer screening activities. Activities involved in breast, colon and cervical cancer screening may serve as potential triggers associated with the original trauma and should be considered and addressed carefully by clinicians. This guide, therefore, includes a resource for Trauma-Informed Population Health Management. For additional information about managing behavioral health conditions beyond screening, please see the behavioral health implementation guide.

For many key activities in this guide, we have highlighted considerations related to social needs at the individual or population level, such as expanding referral networks. Key Activity 14: Use Social Needs Screening to Inform Patient Treatment Plans can help practices better understand and support patient- and population-level needs. For Medi-Cal patients and families with high levels of social need, such as those experiencing homelessness, referrals to Enhanced Care Management (ECM) and Community Supports programs are available; see Key Activity 17: Provide Care Management for more.

For going deeper in this area, practices can see Key Activity 16: Continue to Develop Referral Relationships and Pathways for common social needs and Key Activity 15: Strengthen Community Partnerships to build upon the strengths, infrastructure and resources available in the community. More information about this dual patient- and population- level approach is available in the PHMI Social Health Framework and Approach.

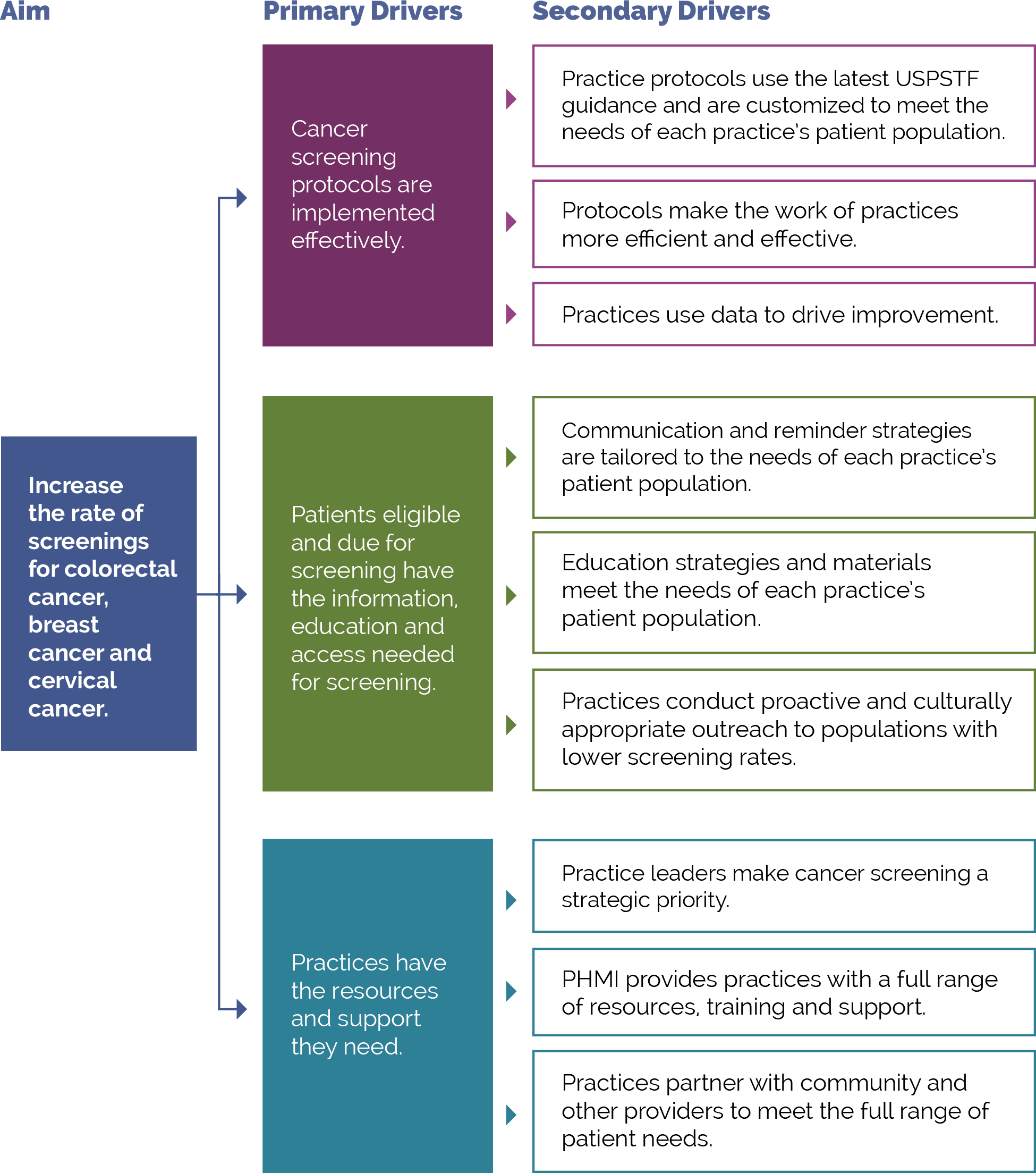

Our theory of change is that if practices implement the activities contained in this guide, it will lead to improved health and well-being outcomes among the adults served by practices. See Appendix B: Theory of Change for a suggested driver diagram.

Foundational Key Activities

Activities that all practices should implement as part of their cancer screening protocol.

KEY ACTIVITY #1:

Convene a Multidisciplinary Implementation Team for Cancer Screening

This activity involves preparing the practice to address all seven elements of person-centered population-based care: operationalize clinical guidelines; implement condition-specific registries; proactive patient outreach and engagement; pre-visit planning and care gap reduction; care coordination; behavioral health integration; address social needs.

Overview

This activity provides guidance for developing, launching and sustaining the multidisciplinary team within your practice that will be responsible for the planning and implementation of all of the key activities in this guide and overseeing related quality improvement and equity efforts, as outlined in Appendix C: Developing a Robust Measurement Strategy.

The implementation team is so important that it appears first in our sequenced list of key activities. Improving your practice’s key outcomes for each population of focus and reducing equity gaps requires the aligned efforts of all care teams and nearly all functional areas of the practice, not just those working directly with patients.

This team is responsible for ensuring that all key activities in this guide, including those related to screening for social needs, are implemented. As you put together this multidisciplinary implementation team, you should identify a diverse group of staff who are reflective of the community served and who represent the lived experience of patients. In addition to implementing the activity focused on and applying a systematic approach to decrease health inequities, the team should apply an equity lens to every step outlined in this guide to help ensure that any improvements are equitably spread among the patient population. To achieve optimal functioning and impact, all members of this diverse multidisciplinary team should have their perspectives proactively included.

Relevant health information technology (HIT) capabilities to support this activity include care guidelines, registries, clinical decision support, care dashboards and reports, quality reports, outreach and engagement, and care management and care coordination (see Appendix E: Guidance on Technological Interventions). To enable team coordination, thought must be given to how to access relevant technology and how data is consistently captured, can be distributed, integrated into workflows, and how data is accessible across team members. Where possible, it is desirable to avoid duplication of data entry, siloing of information in standalone applications and databases, and the need to work in multiple applications requiring separate logins.

Action steps and roles

1. Develop a time-limited group of leaders within the practice to start this process.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Chief medical officer or equivalent and office manager or quality improvement coordinator.

Start with a small group of leaders from your practice (some of whom will be on the implementation team) who can help refine the charge or scope of work of the implementation team and both identify and engage the people/roles that will be required to implement the scope of work of the team.

2. Develop a preliminary scope of work or charge outlining the responsibilities of the implementation team.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Time-limited group of practice leaders.

This scope or charge includes but may not be limited to enabling, aligning, leveraging and supporting the planning and implementation of all foundational key activities in this implementation guide for adults with preventive care needs so that the practice meets the foundational competencies for providing high-quality preventive care.

However, there may be further foundation building work needed at your practice in order for you to succeed at the above key activities. The Population Health Management Capabilities Assessment Tool (PhmCAT) is a multidomain assessment that is used to understand current population health management capabilities of primary care practices. This self-administered tool can help your practice identify opportunities and priorities for improvement.

If your practice has not scored highly in the domains of leadership and culture; the business case for population health management, technology and data infrastructure; or empanelment and access, consider implementing the activities listed in the four guides on Building the Foundation before or in parallel to working on key activities related to adult preventive care.

The multidisciplinary implementation team should include those empowered to make changes in workflows, policies and staff assignments. They should be respected influencers in the organization (early adopters) who can also guide the change management process. They should also include those with expertise in partnering with patients on cancer screenings.

3. Identify leadership and key actors for the implementation team.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Time-limited group of practice leaders.

- Appoint a “champion” or lead person (e.g., “adult prevention implementation coordinator” to oversee the implementation and coordination of the team.

- Identify key staff who will be the core members of the implementation team. Ensure diversity of position and diversity of gender/race/language. Compensate non-employee members of the team equitably for their time (e.g., patients or community members with lived experience).

- For the adult prevention multidisciplinary implementation team, it is important to include members of the care team, the patient support team, outreach team, social support team, and the electronic health record (EHR) or data team. This could include a core team and an expanded team. Potential members include:

- Adult and family primary care providers (e.g., medical doctor (MD), doctor of osteopathic medicine (DO), advanced practice registered nurse (APRN), or a physician assistant (PA)).

- Registered nurse (RN).

- Medical assistant (MA) or licensed vocational nurse (LVN).

- Social worker.

- Care coordinator.

- Community health worker.

- A member of the information technology (IT) or EHR team, (as part of the expanded team).

- QI lead.

- Billing manager or similar (as part of the expanded team).

- A frontline staff member who interfaces with patients by phone and at check-in.

- Invite identified people to become part of the implementation team and ensure that they have designated time for their participation and/or are compensated equitably for their time.

Teams should engage representation from information technology (IT) to support the work of pulling data from the electronic health record (EHR) and embedding updated data into tracking and evaluation.

4. Launch the implementation team and set it up for success.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Clinical coordinator, chief operating officer (COO), or chief medical officer (CMO).

This work includes:

- Ensuring that the team understands their charge or scope of work.

- Developing a team charter outlining this work.

- Defining roles and responsibilities including the anticipated commitment (in hours) on a monthly basis. Create a compensation plan for nonemployee members of your team (e.g., patients or community members).

- Establishing a meeting structure, file structure and communications structure to support effective, efficient work.

- Dedicating time and effort to forming, storming, norming and performing as a team. The Team Communication and Working Styles Template is one tool that team members can complete and share with other teammates to accelerate this process.

- Understanding baseline data related to outcomes of interest (e.g., timely postpartum visits and baseline prenatal depression screening), along with data related to known and perceived barriers to these outcomes. Assess stratified outcomes data to identify quality performance disparities in particular subpopulations.

- Prioritizing elements within the scope of work, informed by baseline data and identified population needs

We recommend that practices consider planning and attempting to implement the activities in the sequence provided in this guide, focusing first on the key activities before focusing on the activities suggested under “Going Deeper” or “On the Horizon.” However, different practices may follow different paths toward implementation

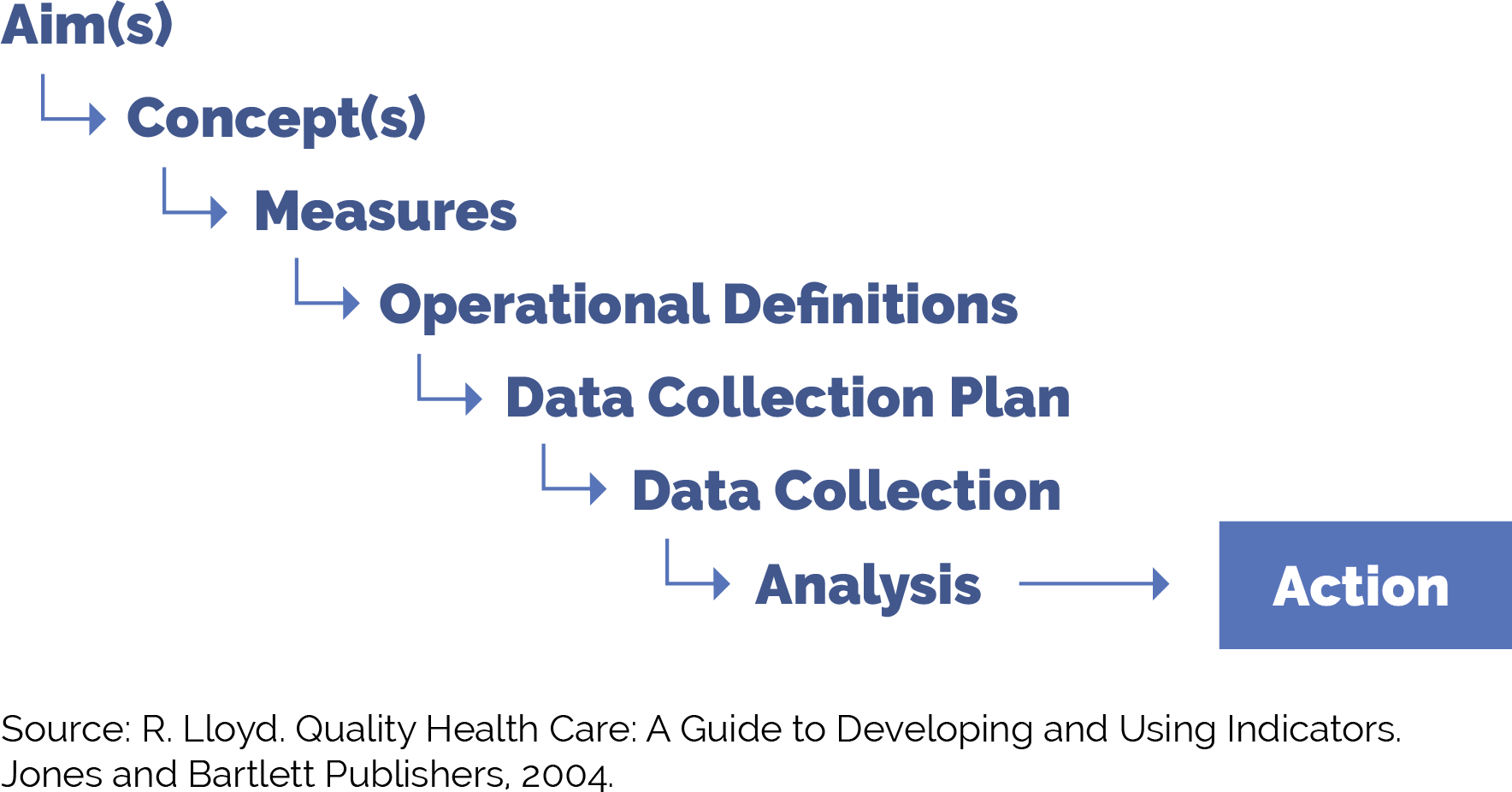

5. Develop a simple yet robust measurement strategy and learning system to guide your improvement efforts.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: QI lead or equivalent.

A learning system enables a group of people to come together to share and learn about a particular topic, to build knowledge and speed up improved outcomes. A simple yet robust measurement strategy and learning system:

- Contains a balanced set of measures looking at outcomes, processes and possibly unintended secondary effects (e.g., increased cycle time and impact on team well-being).

- Incorporates the patient perspective and the perspective of staff (front desk and others), care team members, and management.

- Allows the team to determine if the process or system has improved, stayed the same, or gotten worse.

- Helps guide improvement efforts and informs practice operations. See Appendix A: Sample Idealized System Diagram: Weaving Your Measurement Strategy and Learning System into Practice Operations for a sample system diagram for how your measurement strategy can be used to support practice operations.

Your practice should track the core and supplemental measures for colorectal cancer, breast cancer and cervical cancer screening. These can be considered outcome measures because there is ample evidence that improved timely screening rates will improve overall population health outcomes for cancer survival.

In addition to the core and supplemental measures, practices should track process measures and balancing measures. Appendix C: Developing a Robust Measurement Strategy describes and defines the key milestones in the development of a robust measurement strategy, including definitions for each of these terms.

Suggested process measures:

- Percentage of adults who are sent a reminder regarding colorectal cancer screening who initiate screening activity.

- Percentage of adults who are sent a reminder regarding breast cancer screening who initiate screening activity.

- Percentage of adults who are sent a reminder regarding cervical cancer screening who initiate screening activity.

Suggested balancing measures:

- One or more measures related to patient satisfaction.

- One or more measures related to staff satisfaction.

Practices can also look at other metrics to understand the progress of specific improvement initiatives over time. These may include:

- Progress on the Population Health Management Capabilities Assessment Tool (PhmCAT).

- Progress towards foundational competencies listed in this implementation guide. For example, “Yes or No: Did your practice achieve the following foundational competency ‘Provide or Arrange for Cancer Screening?'

- Any other care gaps, clinical guidelines or measures your practice feels are important to prioritize.

Applying an equity lens

Your practice is likely achieving better outcomes with some patients than others. To understand who the practice is achieving poorer adult prevention outcomes for, practices should stratify their data based on race, ethnicity and language (REAL); sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI); and other patient characteristics (e.g., social needs, etc.) within the Population of Focus. See more in Key Activity 4: Use a Systematic Approach to Address Inequities within the Population of Focus. The ability to segment data in such a manner can lead to profound insights about structural challenges driving some of the health outcomes. The Advancing Equity Through Data Quality and Reporting section of the PHMI Data Quality and Reporting Guide provides more guidance on this.

Putting it all together

We recommend that your practice record your measurement strategy in one place. This Measurement Strategy Tracker contains all the fields we believe are most useful; it can be customized to meet your practice’s needs.

6. Plan and implement regularly scheduled meetings of the implementation team.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: QI lead or equivalent.

- Hold time on team members' calendars for standing meetings. Consider biweekly (twice monthly) meetings to start with. The frequency, duration and focus of these meetings may change as you consider additional populations or subpopulations, additional sites or locations, and the changing nature of the work.

- Develop a system to efficiently report on all work streams and track follow-up items. The Action Plan Template is one tool that can be used to focus your team around the foundational competencies and define responsibility for actions steps to be taken for each project your team has prioritized to work on.

7. Make adjustments based on data from the team’s measurement strategy and feedback loops.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Multidisciplinary team.

- Review data and feedback at least monthly and adapt efforts as needed. Adaptation could include any or all of the following:

- Amending the charge or scope of work.

- Modifying meetings or meeting structures.

- Changing the team composition (adding or removing members).

- Refining key activities to better meet the needs of patients and practice staff and to improve outcomes or reduce inequities.

- Modifying the measurement strategy and/or feedback loops to better understand what is and isn’t happening.

- On an annual basis, the team’s charter and core membership should be reviewed. As the implementation team's goals are met, the team could disband, meet less frequently (e.g., twice per year), or fold this meeting into a similar standing meeting that occurs separately.

See also Appendix D: Peer Examples and Stories from the Field to learn about how others are implementing this activity.

Evidence base for this activity

Pandhi N, Kraft S, Berkson S, Davis S, Kamnetz S, Koslov S, Trowbridge E, Caplan W. Developing primary care teams prepared to improve quality: a mixed-methods evaluation and lessons learned from implementing a microsystems approach. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018 Nov 9;18(1):847. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3650-4. PMID: 30413205; PMCID: PMC6230270.

Sarfaty M, Wender R. How to Increase Colorectal Cancer Screening Rates in Practice. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2007 Nov 1;57(6):354–66.

Percac-Lima S, Grant RW, Green AR, Ashburner JM, Gamba G, Oo S, et al. A Culturally Tailored Navigator Program for Colorectal Cancer Screening in a Community Health Center: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008 Dec 6;24(2):211–7.

Dougherty MK, Brenner AT, Crockett SD, Gupta S, Wheeler SB, Coker-Schwimmer M, et al. Evaluation of Interventions Intended to Increase Colorectal Cancer Screening Rates in the United States. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2018 Dec 1;178(12):1645.

Adams SA, Rohweder CL, Leeman J, Friedman DB, Gizlice Z, Vanderpool RC, et al. Use of Evidence-Based Interventions and Implementation Strategies to Increase Colorectal Cancer Screening in Federally Qualified Health Centers. Journal of Community Health. 2018 May 16;43(6):1044–52.

KEY ACTIVITY #2:

Develop or Update the Practice’s Cancer Screening Protocols

This key activity involves the following elements of person-centered population-based care: operationalize clinical guidelines; implement condition-specific registries; proactive patient outreach and engagement; pre-visit planning and care gap reduction; care coordination.

Overview

This activity provides general guidance for developing or refining a cancer screening protocol that aligns with the PHMI clinical guidelines, establishes clinical and supportive processes that provide a framework for implementing the guidance safely, and leverages the capabilities of appropriate staff to carry out the protocols. It is the foundation of many of the remaining key activities in this implementation guide.

Cancer screening is essential to early detection and treatment of cancers. Aligning a practice’s screening protocols with the relevant guidelines and ensuring a standard team-based approach to identify and address screening status helps to ensure that your practice is able to identify and offer cancer screening to all eligible patients. Early detection and treatment are of critical importance among populations that have a higher incidence of breast, colon and cervical cancer.

The cancer screening protocol includes applying an equity lens to help ensure that barriers to cancer screening are addressed, including economic, social, historical and cultural barriers, and all patients who are eligible for and due for screening, especially those who are at high risk for cancer, receive appropriate screening and follow-up. Key activities in the protocols should be prepared to address relevant social, cultural and linguistic barriers and needs of the population.

Relevant HIT capabilities to support this activity include care guidelines, registries, clinical decision-making support, care dashboards and reports, quality reports, outreach and engagement, and care management and care coordination (See Appendix E: Guidance on Technological Interventions). Reports should have the capacity to filter by provider, location and care team (where applicable).

Access to outside data may be a consideration or requirement (e.g., California Immunization Registry (CAIR) or immunization registry data and data from other practices), as services received outside the health center may be an important part of screening and follow-up. Ideally, this is accomplished by real-time data exchange, but where not possible, it may require manual entry. Reports may need to include not only the EHR but care coordination and population health management applications or freestanding referral registries. While claims data may be helpful in this regard, lag time may impact its usefulness. Patient-facing applications should be strongly considered to promote patient activation by helping assure that patients are informed and appreciative of the nature and importance of recommended care.

Action steps and roles

1. Understand the latest recommendations on who is eligible and needs to be screened for colorectal cancer, breast cancer and/or cervical cancer and how abnormal findings on those screenings should be managed.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Medical director or their designee.

See the clinical practice guidelines section earlier in this guide. Ensure your practice uses the latest guidelines.

2. Develop or update a colorectal cancer screening protocol for your practice.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Medical director or their designee.

- In addition to the USPSTF recommendations linked to in step 1, review the National Cancer Institute’s Colorectal Cancer Screening (PDQ ®) - Health Professional Version and the CDC’s Guidance on Colorectal Screening Tests for additional practical guidance on colorectal cancer screening.

- Include a summary statement on colorectal cancer screening, including:

- The evidence base for colorectal cancer screening.

- Benefits of colorectal cancer screening.

- Potential risks of colorectal cancer screening.

- Recent changes to the practice’s colorectal cancer screening protocol, if any.

- Management of abnormal or suspicious findings, including patient contact information.

- The colorectal cancer screening protocol should include the following sections (see clinical practice guidelines)

- Who the screening protocol applies to, including initiation age and cessation age for those at average risk, and high-risk individuals.

- The screening methods available, including (for each method):

- Name and brief description of the screening method.

- Who and when the screening method are indicated for and any exclusionary criteria for this method.

- The known risks and benefits of the screening method.

- Recommended frequency of screening using this method.

- Who – meaning which role(s) within the practice – can initiate and/or provide screening using this method (see also Key Activity 5: Develop and Implement Standing Orders).

- Guidance for patients on using this method and preparing for the test, including the opportunity for them to ask questions and have them answered.

- Guidance on documenting the screening, including the screening method in the patient’s record.

- Guidance and documentation for patient declination. For more information, see Key Activity 8: Refine and Implement a Pre-Visit Planning Process for guidance on documenting when a patient declines.

- Follow-up of abnormal or suspicious findings for each technique.

- Date the protocol was approved for use.

Here is a sample colorectal cancer screening decision tree that your practice can adapt to meet your protocols. that your practice can adapt to meet your protocols.

3. Develop or update a breast cancer screening protocol for your practice.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Medical director or their designee.

- Practices should consult the guidelines for breast cancer screening in the clinical practice guidelines (hyperlink within document) section earlier in this guide. Practices should also review the National Cancer Institute’s Breast Cancer Screening (PDQ ®) - Health Professional Version, and the CDC’s Breast Cancer Screening Change Package for additional practical guidance on breast cancer screening.

- Include a summary statement on breast cancer screening, including:

- The evidence base for breast cancer screening.

- Benefits of breast cancer screening.

- Potential risks of breast cancer screening.

- Recent changes to the practice’s breast cancer screening protocol, if any.

- The breast cancer screening protocol should include the following sections:

- Who the screening protocol applies to, including initiation and cessation ages, and high-risk individuals.

- The screening method available, including:

- Name and brief description of the screening method (e.g., screening mammography).

- Who the screening method is indicated for and any exclusionary criteria for this method.

- Recommended frequency of screening using this method.

- Who – meaning which role(s) at the practice – can initiate and/or provide screening using this method (see also Key Activity 5: Develop and Implement Standing Orders).

- Guidance for patients on using this method and preparing for the method, including the opportunity for them to ask questions and have them answered.

- Guidance on documenting the screening in the patient’s record.

- Recommended follow-up of abnormal or suspicious findings.

4. Develop or update a cervical cancer screening protocol for your practice.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Medical director or their designee.

- Practices should consult the guidelines for cervical cancer screening in the clinical practice guidelines section in this guide . Practices should also review the National Cancer Institute’s Cervical Cancer Screening (PDQ ®) - Health Professional Version for additional practical guidance on cervical cancer screening.

- Include a summary statement on cervical cancer screening, including:

- The evidence base for cervical cancer screening.

- Benefits of cervical cancer screening.

- Potential risks of cervical cancer screening.

- Recent changes to the practice’s cervical cancer screening protocol, if any.

- The cervical cancer screening protocol should include the following sections:

- Who the screening protocol applies to, including initiation and cessation ages, and high-risk individuals.

- The Screening Methods available, including (for each method):

- Name and brief description of the screening method.

- Who the screening method is indicated for and any exclusionary criteria for this method.

- Recommended frequency of screening using this method.

- Who – meaning which role(s) at the practice – can initiate and/or provide screening using this method (see also Key Activity 5: Develop and Implement Standing Orders).

- Guidance for patients on using this method, including the opportunity for them to ask questions and have them answered.

- Guidance on documenting the screening in the patient’s record.

- Follow-up of abnormal or suspicious findings.

5. Monitor the cancer screening protocol for accuracy and completeness.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Quality improvement lead or their designee.

It is critical to have a system to review and update the cancer screening protocols on a periodic basis, as new research often results in refinements, changes and updates of national recommendations. Ideally, at least one clinical member of the implementation team (see Key Activity 1: Convene and Multidisciplinary Implementation Team for Cancer Screening) should be tasked with reviewing the protocols on a periodic basis (six months or 12 months) and bringing suggested revisions before the team for consideration in modifying the protocols.

As of 2024, clinician representatives participate in the PHMI Clinical Guidelines to review and endorse clinical guidelines, including reviewing updated evidence. See the Clinical Practice Guidelines for Key Medi-Cal Populations of Focus for more information.

Other members of the implementation team should serve in a supportive role to bring identified changes forward to the team for review and consideration.

In addition, the implementation team should create a feedback loop with the practice’s care team about any real or potential gaps or errors in the cancer screening protocol. The cancer screening protocol should be modified as needed whenever changes, errors or gaps are discovered.

See also these related key activities:

- Key Activity 3: Use Care Gap Reports or Registries to Identify All Patients Due for Cancer Screening.

- Key Activity 5: Develop and Implement Standing Orders.

- Key Activity 7: Create and Use Clinician Reminders.

- Key Activity 8: Refine and Implement a Pre-Visit Planning Process.

- Key Activity 9: Partner with Patients to Discuss Cancer Screening During Patient Visits.

- Key Activity 11: Provide or Arrange for Cancer Screening.

- Key Activity 12: Develop and Implement a Follow-Up System for Those Who Have Been Screened.

Example workflow

Step 1: A member of the clinical care delivery team (e.g., MD, DO, APRN, PA) is assigned to be a protocol update lead and will scan the literature, review the cancer screening protocols, and bring suggested updates to the implementation team.

Step 2: At each meeting of the implementation team, a protocol update agenda item is addressed. The protocol update lead brings forward any identified gaps, errors or changes in national standards for the team’s consideration.

Step 3: New information, research and national standards (via USPSTF and others) are brought forward for consideration by the protocol update lead and the evidence base is reviewed. Team members suggest changes and discuss how these changes will be operationalized in the protocol.

Step 4: The protocol update lead drafts the suggested protocol changes and presents them to the implementation team for review and finalization. This process may continue until the implementation team is satisfied with the changes and the new protocol.

Step 5: The protocol update lead assumes responsibility for sharing the new protocol with all members of the team involved in implementation.

Implementation tips

- Assign one or two members of the team to receive and follow up on updates from the USPSTF. These updates automatically alert providers when new recommendations are posted and finalized.

- Review any changes in the guidelines with clinicians and clinical support so that discussions with patients reflect the current recommendations.

- Note the availability of choices in certain types of cancer screening, such as colorectal cancer, and inform patients of the differing testing schedule based on the type of test selected.

- Be sensitive to barriers, such as out-of-pocket expenses, transportation needs, and scheduling needs that affect a patient’s ability to carry out the screening.

- See also Appendix D: Peer Examples and Stories from the Field to learn about how others are implementing this activity.

Resources

Evidence base for this activity

Crosby D, Bhatia S, Brindle KM, Coussens LM, Dive C, Emberton M, Esener S, Fitzgerald RC, Gambhir SS, Kuhn P, Rebbeck TR, Balasubramanian S. Early detection of cancer. Science. 2022 Mar 18;375(6586):eaay9040. doi: 10.1126/science.aay9040. Epub 2022 Mar 18. PMID: 35298272.

KEY ACTIVITY #3:

Use Care Gap Reports or Registries to Identify All Patients Due for Cancer Screening

This key activity involves the following elements of person-centered population-based care: operationalize clinical guidelines; implement condition-specific registries; address social needs.

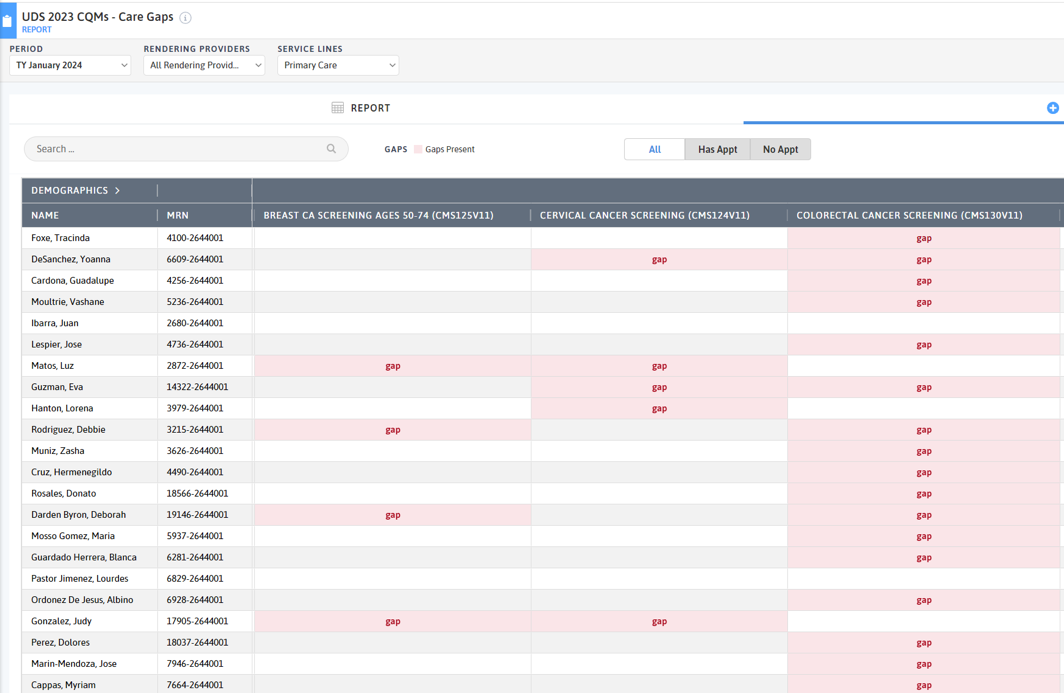

Overview

This key activity provides detailed guidance on how to develop and use a continuously updated list of all patients eligible for recommended screenings through a care gap report or registry. Please note that this activity focuses on specific cancer screenings, but many other preventive and maintenance services are needed to provide comprehensive preventive care. See the Pre-Visit Planning: Leveraging the Team to Identify and Address Gaps in Care resource for a more complete list.

Care gaps are gaps between the recommended care that a patient should receive according to clinical guidelines and the care a patient has actually received.

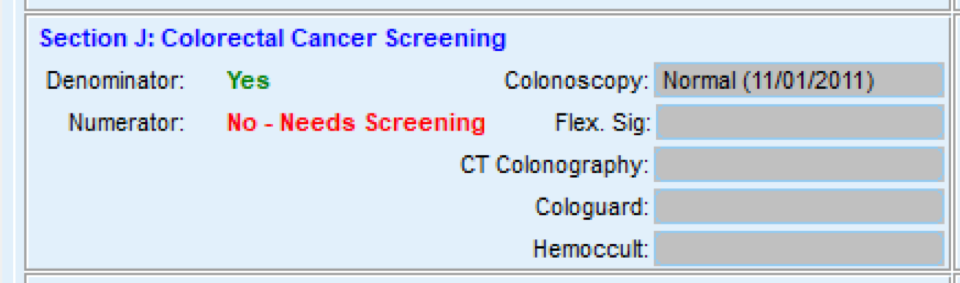

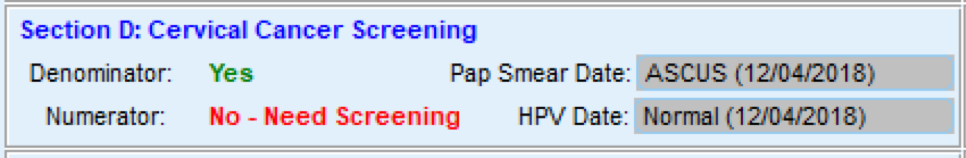

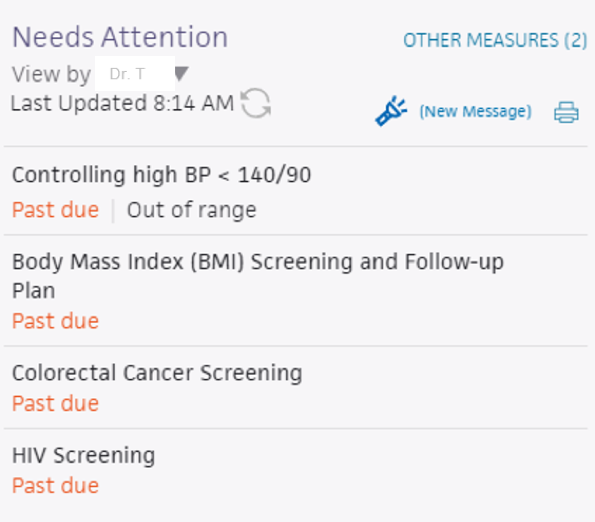

Most EHRs already have a module that identifies what services are due for each patient (see examples below). It is important that clinicians address these services and document efforts to communicate with patients about the screening recommendations, barriers that may affect the patient’s ability to undergo the screening, choices for screening available to the patient, and other relevant information in the EHR. Some patients may have elected to pursue screening through another provider. For example, a person may have obtained a mammogram through an outside provider. Efforts should be made to enter the date of screening into the practice’s EHR and to obtain the results of the screening and enter that information into the EHR through an electronically accessed report or scanning the report.

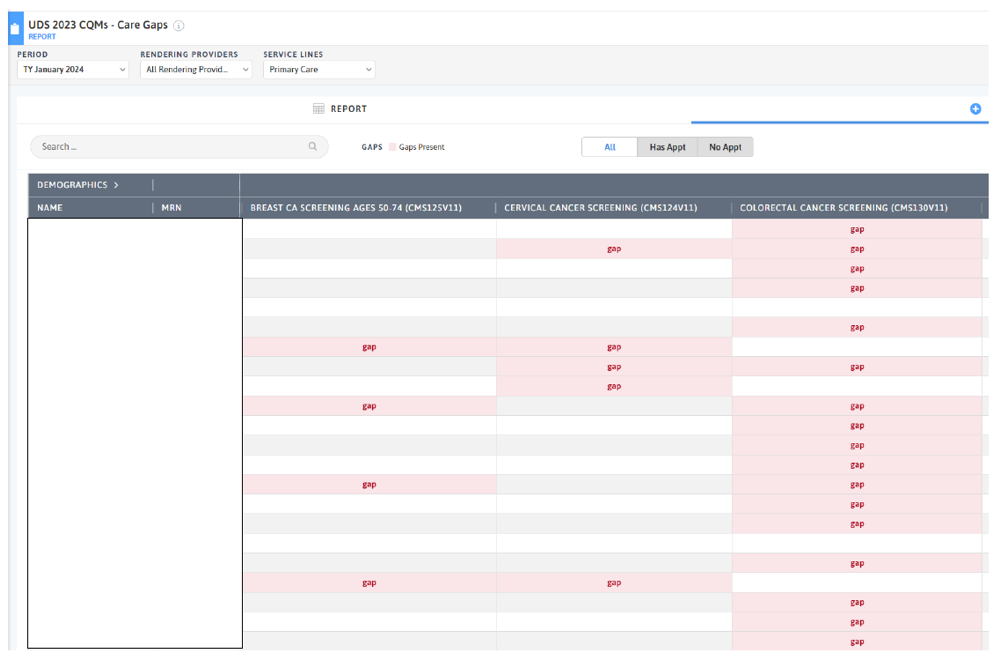

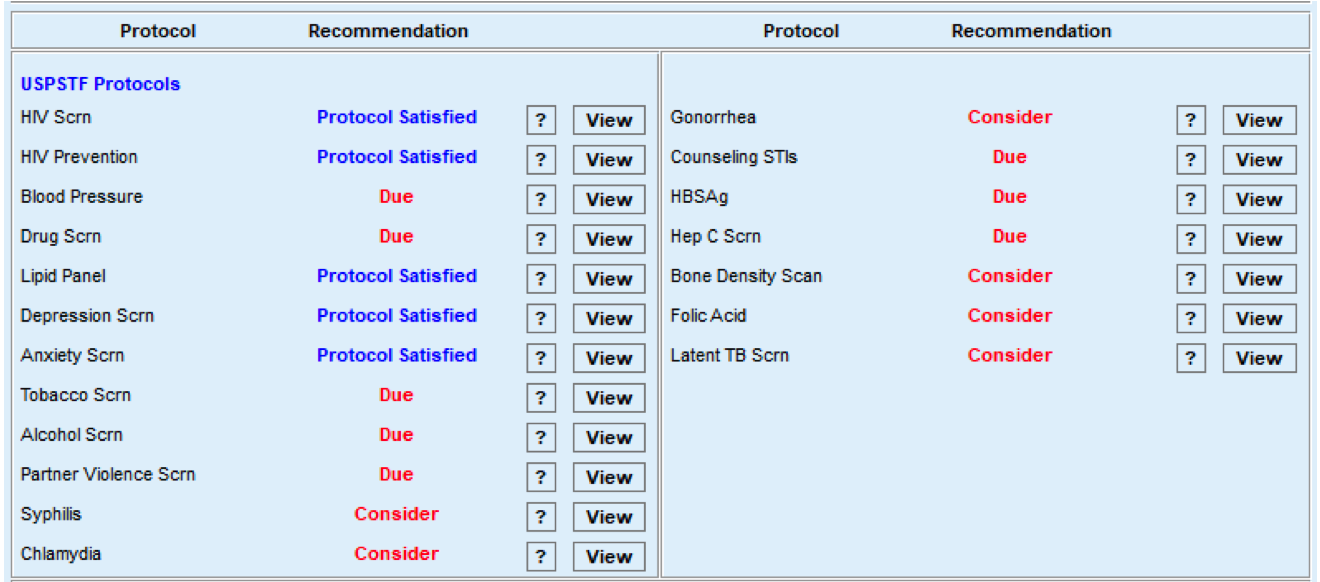

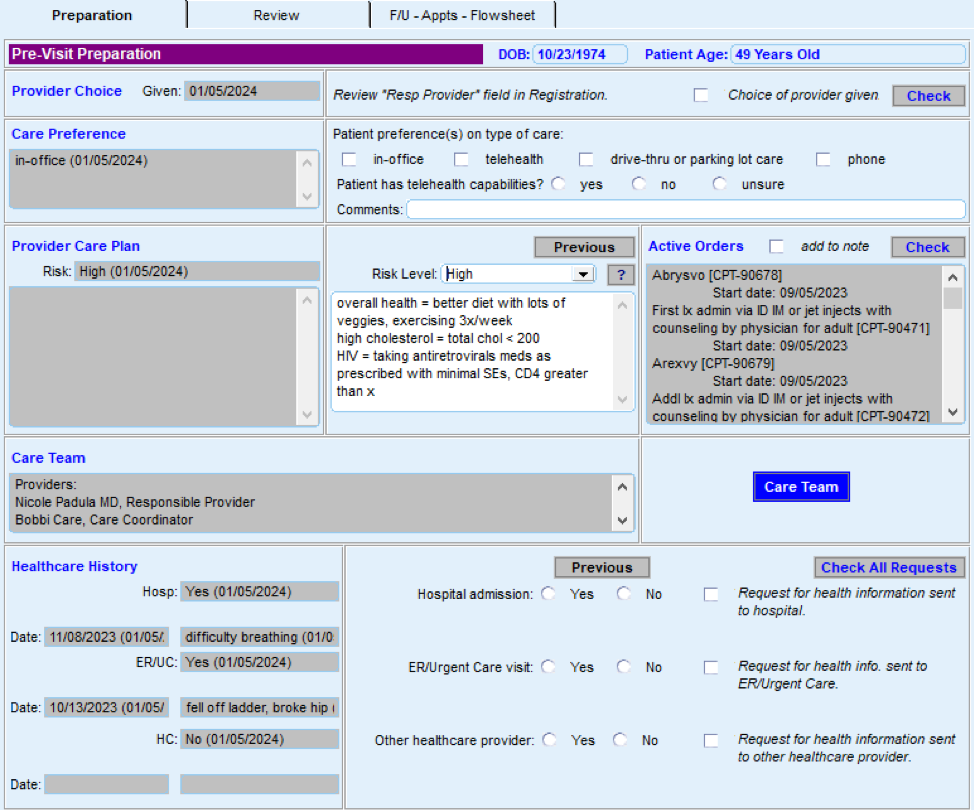

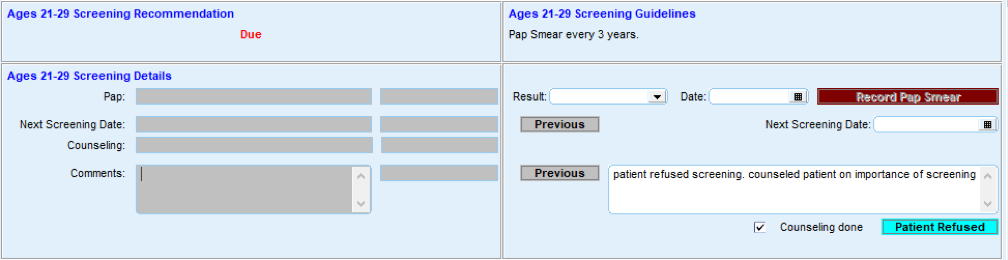

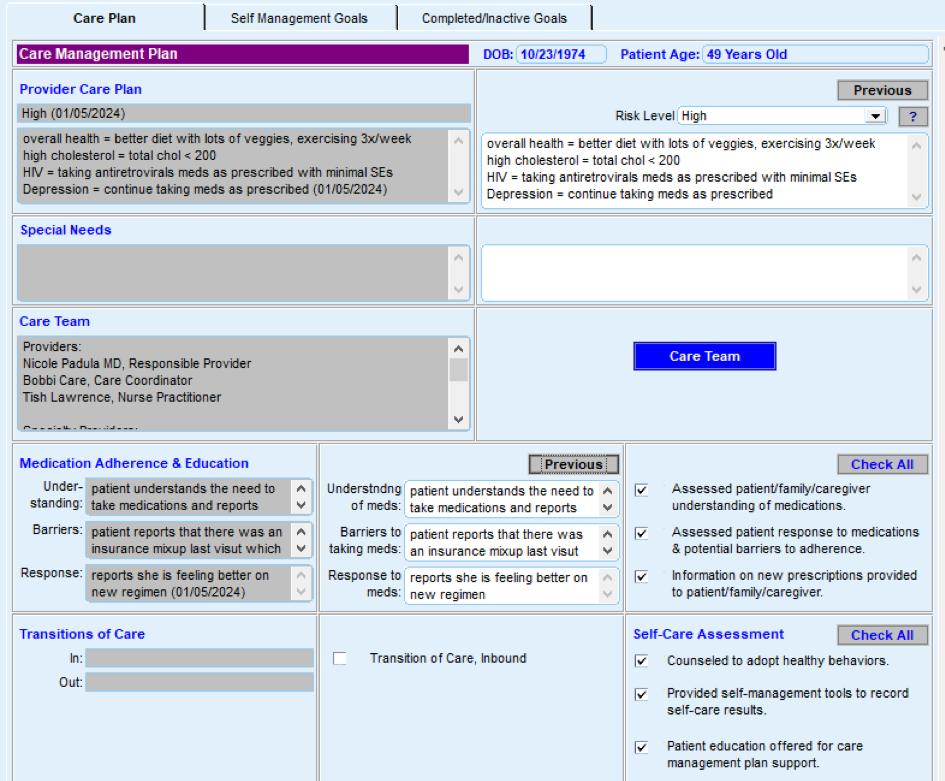

FIGURE 3, FIGURE 4, FIGURE 5: EXAMPLES OF INDIVIDUALS WITH CANCER SCREENING CARE GAPS

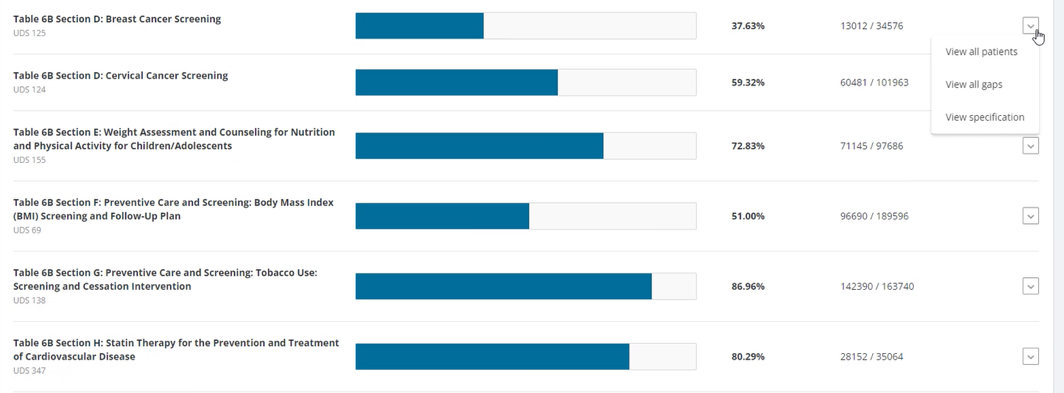

FIGURE 6 AND FIGURE 7: EXAMPLES OF A CARE GAP REPORT.

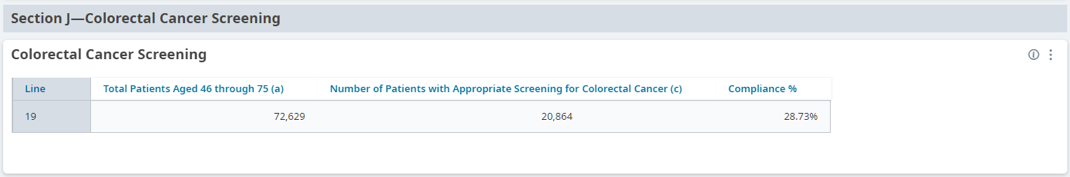

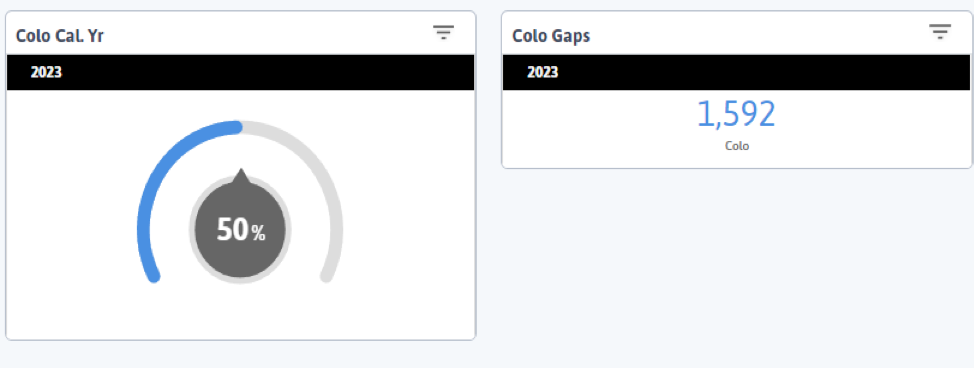

FIGURE 8 AND FIGURE 9: EXAMPLES OF CARE GAP REPORTS FOR A POPULATION FOR COLORECTAL CANCER SCREENING.

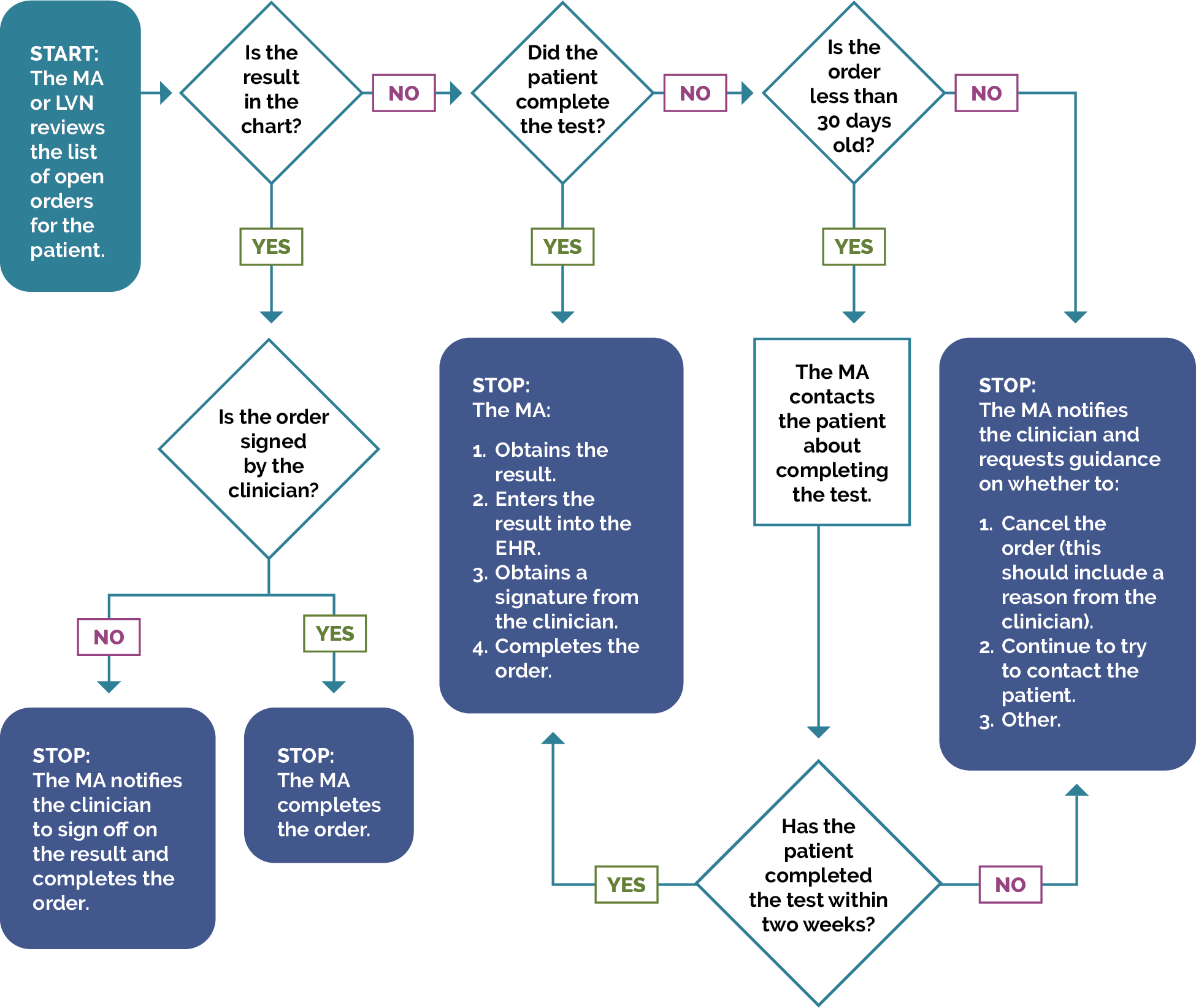

Rather than put the responsibility on the individual care team member for searching through charts or remembering which patients need further preventive care or follow-up, this activity provides guidance for how the practice can efficiently leverage electronic health records (EHRs) for all its patients.

Care gap reports are essential in understanding how well practices are meeting clinical care guidelines for various measures. This awareness supports improvement, consistency and reliability in meeting care guidelines. At the care team level, gap reports focus on due or overdue labs, screenings, or other interventions for patients assigned to your care team. These lists can be used to:

- Support improvements to the pre-visit planning process, develop standing orders, and improve other routine clinical workflows designed to systematically identify and address gaps in care.

- Remind providers of needed orders for a clinical visit.

- Prioritize patients for whom care teams should provide proactive outreach and reminders for engaging in care.

- Support quality improvement efforts with an equity lens.

Actively identifying and acting on care gaps helps to ensure that all eligible patients assigned to your practice receive timely screenings and other preventive services. For adults with preventive health needs, care gap reports can identify patients who are due for regular or infrequent required screenings in accordance with clinical care guidelines, including guidelines that may be established by specific payors.

Many practice patients experience barriers in accessing care due to structural and historical racism, homophobia, xenophobia, and other biases that have historically disadvantaged individuals and groups from receiving equitable services. Defining clear criteria and gaps for patients due for specific screenings or preventive services helps to illuminate groups who have not had equitable access and combats biases by standardizing expectations for who is due for what care, providing a starting point for ensuring reliable and equitable access.

Staff can identify potential barriers to patients accessing and engaging in care by using enhanced care gap reports to filter and display the data alongside demographics, social needs, behavioral health needs, and communication preferences. This information can be used to promote a person-centered approach when designing the care plan and promote self-care and other patient engagement activities, such as conducting outreach in the patients’ preferred language. Furthermore, care gap reports that segment the data into cohorts based on demographic and other personal information may help the team identify inequities in care, access and outcomes, which can inform improvement efforts.

Care gap reports can be used during pre-visit planning to identify people for whom social needs screening has not yet been completed. This creates an opportunity to identify unmet social health needs and connect patients with resources that address their social needs. It also provides an opportunity to identify patients who have undergone screening at another site, obtain screening reports to guide clinical follow up, if needed, and maintain accurate data on patient completion of recommended screening activities.

Many EHRs already have a module that identifies what services are due for each patient, while others do not. Where this functionality is available, it may not be configurable to align with the health center’s specific protocol or be able to incorporate outside data. Other options for developing registries include supplemental applications, population health platforms, and freestanding customized databases that draw data from the EHR and other sources.

Care gap reports may be embedded in electronic health records or made available through other technology channels (see Appendix E: Guidance on Technological Interventions) and are useful both at the individual patient level and aggregated to identify groups of patients to facilitate population level management through registries.

A registry can be thought of as simply a list of patients sharing specific characteristics that can be used for tracking and management. Both care gap reports and registries should have the capacity to segment patients by age, gender, race, ethnicity and language.

Other relevant HIT capabilities to support and relate to this activity include care guidelines, care dashboards and reports, quality reports, outreach and engagement, and care management and care coordination.

See Appendix E: Guidance on Technological Interventions.

Access to outside data may be a consideration or requirement (e.g., CAIR or immunization registry data and data from other practices), as services received outside the health center may be part of compliance. While claims data may be helpful in this regard, lag time may impact its usefulness. Patient-facing applications should be strongly considered to assure they are informed and appreciative of the nature and importance of recommended care. In California, many healthcare organizations are required or have chosen to participate in the California Data Exchange Framework (DxF), which can facilitate data sharing between clinics, managed care plans (MCPs), and other partners.

Action steps and roles

1. Plan the care gap report.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Panel manager or data analyst. If it is not clear how the report can be produced, this step may involve one or more people from the practice who work on the EHR and, possibly, the EHR vendor.

For adults with preventive care needs, use guidance from your cancer screening protocols to build care gap reports for all patients eligible and due for colorectal cancer, breast cancer and cervical cancer screening. Identify the inclusion criteria for each report, such as age, any exclusion criteria, and factors that make someone high-risk. You can build reports across different risk states, such as identifying those with a higher risk for colorectal cancer because of their family history of colorectal cancer, a personal history of inflammatory bowel disease, or a personal history of colorectal polyps.

Generating a report within the EHR is may be more complicated for colorectal cancer screening because multiple testing options are available to patients, and each test has its own frequency recommendation. It is less complicated for breast and cervical cancer.

For colorectal cancer screening, it is essential to know the type of test last performed to determine the retesting schedule. For example, those who have had a fecal immunochemical test (FIT) test for colorectal cancer are recommended to screen annually, while those who underwent colonoscopy are placed on a 10-year schedule, provided that the test results were negative. In all cases, your cancer screening protocols and the care gap report should be updated to capture the latest recommended frequency for rescreening (see Key Activity 2: Develop or Update the Practice’s Cancer Screening Protocols).

2. Build the report.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Data analyst.

Determine whether the EHR has an existing report or one that can be modified to fit the inclusion and exclusion criteria. You should talk to staff who are familiar with the electronic record; in some cases, it may be necessary to consult with the EHR vendor to confirm this information and how to run the report.

The care gap format should include:

- Criteria for inclusion and exclusion in the report.

- The overall compliance rate for the care gap being measured.

- All patients eligible for the screening and their addresses and phone numbers.

- The last date the test was performed, if known or if applicable, the previous results, and the type of test used.

- Preferred method of communication (e.g., phone, email, text).

Reports should be able to display and/or disaggregate the data based on:

- Race, ethnicity and language (REAL) as well as sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI).

- Any known social or behavioral needs.

- Communication preferences or other preferences that would inform the screening modalities offered, such as documented declination of prior screenings.

- Data on any other characteristic, including insurance data, that could pose a barrier to completing screening.

3. Standardize the data format.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Panel manager or data analyst.

Standardizing the data format and where and how it is entered is critical to ensuring accuracy in the report.

Document how each data element must be entered into the EHR to populate the fields needed for reporting. In some cases, data on completion of screening must be entered by hand (e.g., when the test is performed by a lab that does not communicate with the EHR). Doing this will require a decision on the part of the practice as a whole and may require staff training and reinforcement on an ongoing basis. Where issues or apparent confusion are identified, regular discussion at team huddles or staff meetings will help in maintaining a standard approach.

Tip: Assign responsibility for the initial review of the reports to confirm data integrity.

4. Develop workflows to support improved patient screening completion rates.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Panel manager and care team.

At the patient level, ensure that the care gap report can be used for or linked with reminders or alerts for clinicians, as well as for sending reminders to adults who need to come into the practice for recommended cancer screening.

Depending on communication preferences that have been expressed by patients, the patient care gap report may be exported to an automated reminder system that can trigger reminders by phone, text, email, or postal mail. Several studies and case studies have indicated that personal calls are more effective, so in the absence of a known patient preference, practices should consider personal calls as a strong option.

For adults with preventive care needs, cancer screening reminders can get particularly complicated. See Key Activity 7: Create and Use Clinician Reminders.

In addition, as part of the practice’s pre-planning process, patient care gaps should be reviewed and flagged as part of the daily huddle. See Key Activity 8: Refine and Implement a Pre-Visit Planning Process for more details.

5. Develop a process for review of gaps at the population level.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Panel manager.

Set a report frequency to review care gap reports at regular care team meetings or huddles to develop a plan for improvement at the population level. This may include an outreach campaign to build community awareness of the value of screenings and the availability of easily accessed screening services.

6. Monitor the care gap report for accuracy and completeness.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Panel manager or data analyst.

It is critical to have bidirectional feedback with the practice’s care team about any real or potential errors in the care gap report, such as:

- Errors in how the data is entered compared to what is required under the new standardized data format.

- Patients who are eligible for and due for screening who are missing from the report.

- Patients who have recently been screened who are still listed as due for a screening.

Errors should be investigated through a chart review. If errors in the report specifications are discovered, the care gap report or process for producing the report should be modified. If the issue is incorrect documentation, staff training and reinforcement of documentation standards will be required.

Additional consideration for sustainability: Ensure there is an internal process for updating the criteria included in the EHR for care gap reports as clinical guidelines change.

See also Appendix D: Peer Examples and Stories from the Field to learn about how others are implementing this activity.

Resources

Evidence base for this activity

Conderino S, Bendik S, Richards TB, Pulgarin C, Chan PY, Townsend J, Lim S, Roberts TR, Thorpe LE. The use of electronic health records to inform cancer surveillance efforts: a scoping review and test of indicators for public health surveillance of cancer prevention and control. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2022 Apr 6;22(1):91. doi: 10.1186/s12911-022-01831-8. PMID: 35387655; PMCID: PMC8985310.

Sequist TD, Zaslavsky AM, Marshall R, Fletcher RH, Ayanian JZ. Patient and physician reminders to promote colorectal cancer screening: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009 Feb 23;169(4):364-71.

KEY ACTIVITY #4:

Use a Systematic Approach to Address Inequities within the Population of Focus

This key activity involves all seven elements of person-centered population-based care: operationalize clinical guidelines; implement condition-specific registries; proactive patient outreach and engagement; pre-visit planning and care gap reduction; care coordination; behavioral health integration; address social needs.

Overview

This activity provides guidance for a systematic, evidence-based approach for identifying and then reducing inequities for adults with preventive care needs. It focuses on the first primary driver in PHMI’s equity framework: Reduce inequities for populations of focus.

FIGURE 10: PHMI DRIVER DIAGRAM

Your practice likely achieves better outcomes with certain populations or subpopulations and worse outcomes with others. Inequitable outcomes are often the result of social and cultural factors that serve as barriers to accessing care and are generally most acute among persons of color, immigrants, persons speaking a primary language other than English, and other populations who have been marginalized. As we work to reduce and eliminate inequitable health outcomes over time, we need to understand both what contributes to these different outcomes, as well as factors that do not contribute to them.

This includes recognizing that race is a social construct determined by society’s perception. While some conditions are more common among people of certain heritage, inequities in conditions, such as cancer, diabetes, and adverse maternal outcomes, have no genetic basis. While genetics do not play a role in these inequitable outcomes, the extent to which inequities in the quality of care received by people of color contribute to inequitable health outcomes has been extensively documented[3]. These inequities are often a direct result of racism, particularly institutionalized racism – that is, the differential access to the goods, services, and opportunities of a society by race[4]. Racial health inequities are evidence that the social categories of race and ethnicity have biological consequences due to the impact of racism and social inequality on people’s health[5]. It is also critical to recognize that we have policies, systems and procedures that unintentionally cause inequitable outcomes for racial, ethnic, language and other minorities in spite of our genuine intentions to provide equitable care and produce equitable health outcomes.

Improving your practice’s key outcomes for each population of focus requires a systematic approach to identifying equity gaps (e.g., who your practice is not yet achieving equitable outcomes for) and then using quality improvement (QI), collaborative design, systems thinking and related methods to reduce these equity gaps.

Identifying and meeting patients’ social health needs is a key driver of reducing inequitable health outcomes. We provide additional guidance in this activity on how to both reduce inequities and meet patients’ social health needs.

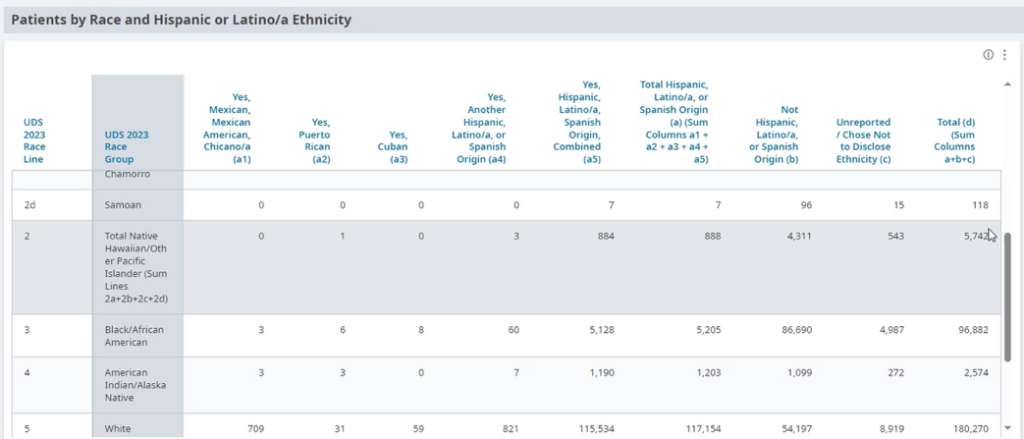

Access to data required to identify and monitor inequities, as outlined in the key actions outlined below, is fundamental to this activity.

EHRs have the ability to capture basic underlying socioeconomic, SOGI and social needs-related data but may in some cases lack granularity or nuances that may be important for subpopulations. Mismatches between how the Uniform Data System (UDS) captures REAL data versus how EHRs capture or MCPs report data can also create challenges. This may require using workarounds to capture these details. It is also important to ensure that other applications in use that may have separate patient registration processes are aligned. Furthermore, tracking inequities in accessing services not provided by the health center may also require attention to data sources or applications outside the EHR.

Health centers should also be alert to the potential for technology as a contributor to inequities. For example, patient access to telehealth services from your practice may be limited by the inequitable distribution of broadband networks and patient financial resources (e.g., for phones, tablets, and cellular data plans). EHR-embedded algorithms used to risk stratify populations may also contain inherent racial biases. The Techquity framework can be a useful way to structure an approach to assure that technology promotes rather than exacerbates disparity.

Language, literacy levels, technology access and technology literacy should also be considered and assessed against the populations served at the health center.

Finally, attention needs to be paid to use of best practices in collecting the data, accurate categories in the technologies in which it is collected and stored, and adequate training and monitoring of staff responsible in order to ensure that reports and analysis have a valid basis.

Relevant HIT capabilities to support this activity include care guidelines, registries, clinical decision support (e.g., modifications required to consider disparate groups), care dashboards and reports, quality reports, outreach and engagement, and care management and care coordination see Appendix E: Guidance on Technological Interventions.

Action steps and roles

1. Build the data infrastructure needed to accurately collect REAL, SOGI, social needs and other demographic data.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Data analyst.

- Race, ethnicity and language (REAL).

- Sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI).

The PHMI Data Quality and Reporting Guide provides guidance and several resources for collecting this information. According to this guide, the initial step in addressing disparities is to collect high-quality data that fosters a holistic view of patient characteristics and needs. This entails incorporating REAL data, demographic data (age, SOGI, geography) and social needs data. By collecting and monitoring this information, healthcare practices can gain valuable insights into disparities in access, continuity and health outcomes. Steps two to four below provide more information on this process.

Collecting REAL information allows for practices to identify and measure disparities in care while also ensuring that practices are able to interact successfully with patients. This is done by understanding patients’ unique culture and language preferences.[6] KHA Quality has a toolbox that assists with REAL data collection.

The Uniform Data System (UDS) Health Center Data Reporting Requirements (2023 Manual) provides detailed guidance on REAL and SOGI. While UDS does not currently require that practices report on the preferred language of each patient, practices should make an effort to identify and record each patient’s preferred language due to UDS reporting still requiring for languages other than English to be reported.

Accurate data collection requires appropriate fields and options in the EHR and other employed technologies, as well as appropriate human workflows in collecting the data. Staff responsible for data collection should be continuously trained and assessed for best practices in data collection, including promotion of patient self-report.

In addition, practices should work to ensure that patients understand the importance and use of this information to help them feel comfortable and support its collection. High rates of “undetermined” or “declined” responses in these fields may be indicative of the need to attend to these staff training needs.

Collecting this data is important, especially to obtain a complete picture of health for patients who identify as transgender. There are certain risks and condition indicators that are gender-specific, which impact how providers provide care to a patient. This should also be taken into account for cancer screenings for patients who have transitioned but carry the risk of certain cancers based upon their gender at birth and degree of transitioning (e.g., a transgender male who still has a cervix may still be at risk for cervical cancer). By understanding the needs of patients more fully, providers can make more informed decisions for the best treatment of their patients. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) has provided further guidance regarding standards of care related to gender diversity.

2. Use the practice’s electronic health record (EHR) and/or population health management tool to understand inequitable health outcomes at your practice by stratifying your data.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Data analyst.

This includes reviewing your care gap report or care registry and being able to stratify all of the following:

- Core measures for the population of focus.

- Supplemental measures for the population of focus.

- Process measures for the population of focus.

Stratify this data by:

- Race, ethnicity and language (REAL).

- Sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI).

- Other factors that can help identify subpopulations in need of focused intervention to reduce an equity gap (e.g., immigrants, people experiencing homelessness, literacy levels, etc.).

FIGURE 11: EXAMPLE OF DATA STRATIFIED BY RACE AND ETHNICITY.

This is not a one-time event, but rather a continuous process (see step 13 below) and should be done in tandem with step three below.

Each practice should define the frequency of review and use of their registry to stratify data for adult preventive care. In early use, the stratified data will support the identification of areas of inequity and allow for prioritization of interventions.

3. Screen patients for social needs.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Care team.

Key Activity 14: Use Social Needs Screening to Inform Patient Treatment Plans provides guidance on screening patients for health-related social needs and how the information can begin to be used to inform patient treatment plans, including referral to community-based services.

This is not a one-time event, but rather a continuous process and should be done in tandem with step two above.

4. Analyze the stratified data from steps two and three to identify patterns in inequitable outcomes within the population of focus.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Data analyst

This includes:

- Using data tools to visualize and understand disparities across different populations or subpopulations.

- Data over time (using run charts).

- Exploring trends, patterns and significant differences to understand which demographic groups will require a focused effort to close equity gaps.

This is not a one-time event, but rather a continuous process (see step 13 below) and should be done in tandem with step two (above) and step four (below).

Periodic review of the stratified data allows for the recognition of gap closures and the emergence of new disparities.

5. Conduct a root cause analysis for each population or demographic group that the practice does not yet have equitable outcomes for.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Multidisciplinary team.

Select root cause analysis approaches that work best for the equity gap you are closing:

- Engage and gather information from patients affected by the health outcome in your root cause analysis (see step six).

- Brainstorming.

- Systems thinking (understanding how interconnected social, economic, cultural and healthcare access factors may be impacting the health outcome).

- Tools that rank root causes by their impact and the feasibility of addressing them (e.g., prioritization matrix and/or an impact effort matrix)

- Visual mapping of root causes and effects (e.g., fishbone diagram).

- Perform focused investigations into selected root causes and gather qualitative data through interviews, surveys or focus groups with the subpopulation of focus.

Present the findings to a broader group of stakeholders, including affected community members, to validate the identified root causes and gain additional insights. Incorporate their feedback and refine the analysis, as needed.

6. Partner with patients to develop additional insights that will help you develop successful strategies.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Care team and people with lived experience (e.g., patients who are representative of the population(s) of focus).

Using one or more human-centered design methods such as focus groups, 7- Stories, Journey mapping, etc. (see links to these methods below), work with members of each population of focus to better understand their:

- Assets, needs and preferences, as they relate to adult prevention recommendations.

- Cultural beliefs, including traditional healing practices that may impact their understanding of or willingness to engage in certain adult prevention practices.

- Beliefs and level of trust in healthcare generally and in the topic of focus specifically (e.g., cancer screening, immunizations, behavioral health, etc.)

- Barriers to accessing care, including health insurance, transportation, childcare, housing access and other social factors.

- Barriers to remaining engaged in care, including the above-noted barriers, and including cultural beliefs, trust, and concerns about follow-up requirements.

- Trusted sources of information and communication mechanisms and preferences for this population.

- Ideas for improving health outcomes as they relate to the uptake of preventive care.

The patients you partner with for this and other steps in this activity may be part of a formal or informal patient group and/or identified and engaged specifically for this equity work.

7. Identify key activities that address or partially address the identified equity gaps.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Care team

Based upon the insights your practice has developed for a population of focus and your root cause analysis, determine which of the key activities could address or partially address the equity gap.

Most of the key activities either explicitly address an equity challenge or can be adapted to better address an equity challenge. Examples of key activities that can be adapted to reduce identified equity gaps include but are not limited to:

- Key Activity 6: Conduct Proactive Outreach to Patients Due for Screening.

- Key Activity 13: Coordinate Care.

- Key Activity 14: Use Social Needs Screening to Inform Patient Treatment Plans.

- Key Activity 15: Strengthen Community Partnerships.

- Key Activity 16: Continue to Develop Referral Relationships and Pathways.

8. Develop new strategies and ideas to address the identified equity gaps.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Care team and people with lived experience.

If one or more of your root causes cannot be addressed fully through key activities, use one or more human-centered design methods (see resources below), to develop ideas to improve health outcomes and reduce inequities among adults with preventive care needs.

Developing these ideas is best done with representatives of the population of focus, as they have expertise and experience that may be missing from the practice’s care team. Compensating these patients and community members for time spent on improvement activities is a best practice. During this brainstorm, you are developing ideas without immediate judgment of the ideas in an effort to generate dozens of potentially viable ideas.

Selected resources on human-centered design and collaborative design:

- Center for Care Innovations (CCI) Human-Centered Design Curriculum.

- IDEO’s Field Guide to Human-Centered Design.

- IDEO’s Design Kit: Methods.

9. Determine which strategies to test first.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Care team and people with lived experience.

Steps seven and eight above help your practice identify existing key activities and generate new ideas. Your practice likely doesn’t have the bandwidth to test all of them, at least not at the same time, so now is the time to prioritize a few to begin testing.

There are many ways to prioritize ideas. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) often recommends a prioritization matrix and/or an impact effort matrix.

If you have organized your key activities and new ideas into themes or categories, you may choose to work on one category or select one to two ideas per category to work on.

The number of key activities and/or new ideas that you prioritize for testing first should be based on the team’s bandwidth to engage in testing. So, it is critical to determine the bandwidth for the team(s) who will be doing the testing so that you can determine how many ideas to test first.

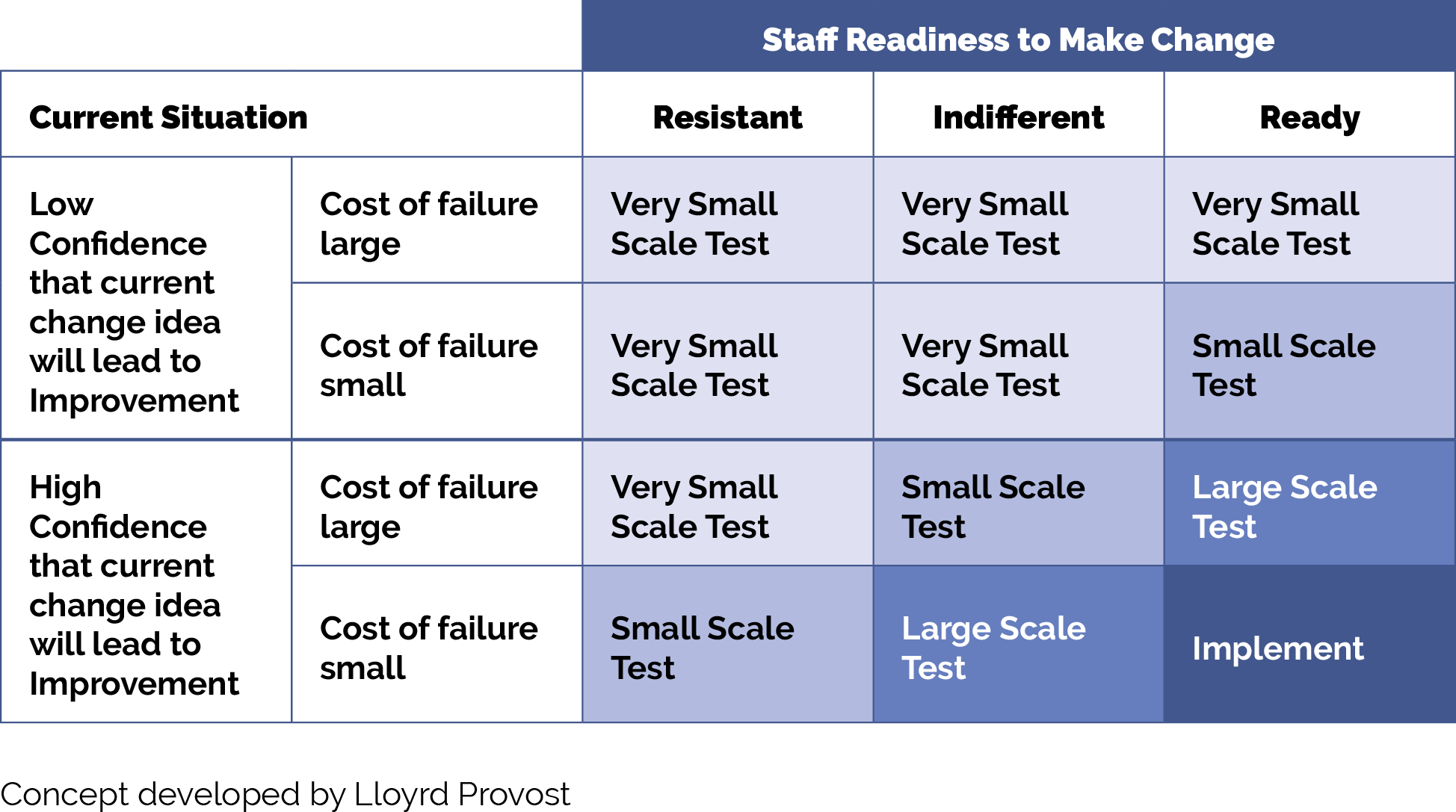

10. Use quality improvement (QI) methods to begin testing your prioritized key activities and new ideas for and with the population of focus.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: Care team and people with lived experience.

Nearly all of the key activities and all of your new ideas will require some degree of adaptation for use within your practice and to be culturally relevant and appropriate to your population(s) of focus.

Use plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles as feasible, generally starting as small as possible – think “ones” (e.g., one clinician, one hour, one patient, etc.) – and become larger as your degree of belief in the intervention grows.

Whenever testing an activity or new idea, we recommend that the practice:

- Use plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles to test your ideas and bring them to scale. See more information on PDSAs below in the tips and resources section.

- Generally, start with smaller scale tests (e.g., test with one patient, for one afternoon, in a mailing to 10 patients, etc.). Use Figure 12: How Big Should My Test Be?, in the tips and resources section to help you decide what size test is most appropriate.

Develop or refine your learning and measurement system for the ideas you are testing. A simple, yet robust learning and measurement system will help you know if your ideas are having their intended effect, if they are having unintended secondary effects (e.g., staff burnout), and how the overall implementation process is going. Consider the following:

- What core measures, supplemental measures and/or process measures is this intervention designed to improve equity for?

- What are or will be the first or early indications that the intervention or idea is working?

- How will you know how the implementation itself is going from a patient perspective, a staff perspective, and a management perspective?

- What are some balancing measures to monitor for the implementation itself and for the time and resources spent on implementation?

- Study the successes and challenges of the test. When feasible, this should include getting feedback from patients directly after testing a new idea with them and incorporating their feedback into your next test.

- Refining the idea, as needed, based on the test.

- Then testing again, increasing on the scale of the test as these tests result in few challenges and better results.