©️ 2024 Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

Recent research shows that a single primary care provider (PCP) would need 26.7 hours in a day to provide all the evidence-based preventive, chronic illness and acute care to an average panel of patients.[1] The good news is that a single provider does not have to do it all! Team-based care when two or more healthcare professionals work collaboratively with patients and their caregivers to accomplish shared goals[2]—can help practices to deliver high-quality primary care leading to better health outcomes[3] and experiences for patients.[4]

Strengthening care teams is increasingly recognized as a critical foundation for high-performing primary care, with California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Cal (CalAIM) adding community health workers and doula services as covered benefits. Engaging nurses, behavioral health specialists, lay health workers, medical assistants and others as key partners in caring for patients increases access to behavioral health and social need services.[5] Sharing the work of primary care among a team of professionals can improve staff and provider experiences, a critical consideration in this post-COVID environment when the healthcare workforce is struggling with burnout and overwork.[6]

Creating high-performing primary care teams can be done in a range of settings, but always requires focusing on both the technical aspects of task and workflow redesign, as well as the communication and trust that binds a team together.[7] The Center for Excellence in Primary Care at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) describes best practices of high performing team-based care, including:

- Embracing a culture shift where team members share responsibility for and contribute meaningfully to the health of their patient panel.

- Establishing efficient workflows with standard processes and team member functions.

- Effective communication that is promoted through regular team meetings, daily huddles and real-time interaction.

These guides are designed to be helpful as part of an organized quality improvement strategy, with the goal of supporting substantive cultural, technological and process changes that improve population-based care. Enterprising practices can take on this work on their own with internal champions, including quality improvement, clinical and program leaders. They may be supported by practice facilitators, coaches or external consultants who help primary care practices improve population health management.

There are a lot of factors that impact an organization’s ability to create high functioning team-based care, some of which are in an organization’s control (e.g. leadership that fosters psychological safety) and others that are not (e.g. the state’s scope of practice policies). [8]

The central content of this guide is organized into a sequenced set of key activities within a practice’s locus of control. These key activities are evidence-based or best practice-based ideas that, when applied to your local clinical context, can lead to improved ways of working. How different practices apply these ideas will vary based on external factors, such as payment structure, union environment and local workforce context. An on-site leader or champion can motivate peers and help in adapting the content for your setting, size, patient population and context.

This guide offers a practical, tested approach to building and supporting team-based care, starting with the intentional identification of a core team of people who together can provide care for most patient needs on their panel. By centering continuous healing relationships between patients and care teams, the guide then shows how to build out the expanded care team to assure the functions of high performing primary care are in place, including a quality improvement approach. The guide offers an index model for how different care team roles can help to support those functions, including licensure and full-time equivalency (FTE) considerations.

The guide also offers ideas for how to Advance Equity through your work on care teams and workforce, and provides guidance for Supporting Change through change management strategies.

For organizations interested in Going Deeper, additional content is available on facilitating teamwork and fostering joy in work. Finally, the guide covers team-based care topics On the Horizon, such as structuring teams for virtual care and thinking about care provision outside the walls of traditional primary care clinics.

Reimagining care teams impacts everyone in a practice, as it impacts care delivery, communication, culture and budgets. Critical leadership roles needed to support an organization’s approach, include:

- Clinical leadership, like a chief medical officer, to design and support care team changes, including changes to clinical schedules and coverage arrangements.

- Financial leadership, like a chief financial officer, to examine revenue and expense implications of modifying, adding or removing care team roles.

- Quality improvement leadership, like a director of quality improvement (QI), to support cultural changes and reimagine how teams work, including fostering communication and trust.

- Human resources leadership to advocate for equitable hiring practices, understand the state’s scope of practice and licensure changes, and explore creative pipeline development, recruitment and retention strategies.

In addition to strong, aligned leadership, care team members themselves must be part of any effort to redesign care teams. Doctors, nurses, community health workers and behavioral health providers know the needs of their patients best, and have critical insights into how current role and task distribution works—or doesn’t. Care team redesign means changing what people are asked to do each day. Involving staff and providers in the design of and decision-making about their work is critical to get the best ideas and create lasting change.

Finally, patients and families should provide important input on how care teams are organized and what services should be prioritized that will best help them meet their goals for health and well-being.

The primary care team comprises the “providers and staff in a practice that collaborate to provide comprehensive, high-quality services to a defined panel of patients.”[9] The licensure and training of the providers and staff who comprise the team will vary based on the needs of the panel of patients served and the workforce’s availability and organizational context. At its core, the team should be organized to accomplish key functions of high performing primary care, including:[10]

- Organized, evidence-based care.

- Social health support.

- Population health management.

- Improved access.

- Behavioral health integration.

- Medication management.

- Health education, care coordination and care management.

- Quality improvement.

How big should this team be? To preserve the benefits of relational continuity between patients, families and their care teams, the size of the team has to be manageable; patients, providers and staff have to be able to identify who makes up the team. We also know that coordination and communication overhead increases as the team size grows.[11][12][13]

By wrapping core teams and expanded care teams around patients and their families, primary care practices can deliver the many functions described above while still centering relationships, community resources and connections.

FIGURE 1: PRIMARY CARE TEAM: CORE AND EXPANDED CARE TEAMS AND THE FUNCTIONS EACH PERFORMS

The core care team includes the primary care providers and key staff who would huddle daily and spend most of their time managing the needs of a panel, which include social health and behavioral health needs.

The expanded care team members are shared across multiple care teams and serve multiple patient panels. These roles include those that focus on:

- Population health management and data analytics.

- Behavioral health consultants to support the core care team behavioral health specialists and provide behavioral health integration.

- Care coordination and care management, including health education to support self-management.

- Medication management.

- Quality improvement.

Building strong core and expanded care teams ensures practices have what they need to tackle upcoming population health management activities. It provides the foundation for a variety of proactive schedule and panel management practices, such as daily schedule scrubbing and huddling, conducting care gap outreach calls to patients with chronic conditions, and systematic identification and addressing of social and behavioral health needs.

In this guide, an index model for core and expanded teams is offered. The index model provided here draws from current best practices and evidence published in the peer-reviewed literature, primarily work done by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and by Dr. Ed Wagner on optimal workforce configurations that provide high-quality, comprehensive primary care.[14] Their analysis was based on data of more than 70 high performing practices that participated in several national primary care innovation programs and insight from in-depth case studies and an expert panel. Input through the co-design processes and Kaiser Permanente’s experience were all considered in the model development, including identifying the index panel size of 1,250. This index model is intended as a starting point for discussion, recognizing that the heterogeneity of patient needs and organizational context naturally results in variation.

Regardless of the precise core and expanded care team composition in high-performing teams, each individual contributes their unique skills and expertise to support whole person healthcare for a panel of patients. Spreading the work of providing preventive, chronic and acute care across the care team requires each team member to work at the top of their license, and may involve reimagining traditional roles and responsibilities. When working well, care teams can describe their:

- Shared goals.

- Distinct and well defined roles and responsibilities.

- Shared standards and norms for communication and cross coverage.

- Common approach to problem solving and process improvement.

- Dedicated time to building team cohesion and collaboration.

The key activities below walk through both the technical and cultural considerations for setting up core and expanded care teams, including engaging with patients and leveraging teams to deliver and improve care.

Key Activities

The key activities below will guide you through the process:

- Develop and test a core care team structure.

- Identify gaps in staffing and decide how to address them.

- Engage patients.

- Leverage teams to lead continuous improvements.

After working through the key activities above, you will be able to:

- Define and establish a core care team incorporating team-based care principles.

- Assure that care teams know their patient panels (applies only if the practice is also working on empanelment or has it in place).

- Assure that patients know their care team.

- Build expanded care team functions that incorporate team-based care principles.

Key Activity #1: Develop and test a core team structure.

The core team is the heart of a practice, and is designed to meet most of the needs of most patients. This core team is where continuous healing relationships between patients and families occur, and is the primary source of healing and value in health care.

1. Understand your patients’ needs.

Delivering high-quality, comprehensive primary care means that teams should be built to address most of the common needs of their patients, and should “have the capacity to either directly deal with them or have the diagnostic skills to appropriately refer the patient to a specialist.”[15] For most primary care practices that care for a general population, the core care team will include, at a minimum, a primary care provider and medical assistant. However, for many practices that serve people with complex social and behavioral health needs, additional capabilities are needed on the core team day to day. Having clearly defined patient panels is the starting point for understanding patient needs and designing care teams to address them. See the Empanelment Guide for more on how to master empanelment, including the bidirectional process of patients choosing a provider, and providers knowing their patient panel.

If your care team is established to address a specific subpopulation of patients, other care team roles may be required. For example, the maternity care population is a special population that requires time bound, condition-specific services to support a healthy pregnancy, birth and postpartum transition. While not all practices provide the full spectrum of prenatal and postpartum services, some may add perinatal services staff if their focus is on improving perinatal outcomes. Care team roles specific to the maternity care population may include a Comprehensive Perinatal Services Program (CPSP) worker and doulas to provide personal support to pregnant persons and families throughout the pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum experience.

2. Identify a core care team that, together, meets most patient needs.

As you explore your patients’ needs, think about how the medical, social, and behavioral health needs of your patients are being met. For many practices, the prevalence of these needs is such that adding capabilities to address them in the core team feels imperative. The index model for the core team is outlined below.

FIGURE 2: SUMMARY TABLE OF THE CORE CARE TEAM MODEL

Team Member |

Role |

Recommended Full-Time Equivalent (FTE) Per Panel |

|---|---|---|

Primary Care Provider (PCP) |

Provides direct patient care, including diagnoses and treatment. |

1.00 FTE to 1,250 patients |

Medical Assistant (MA) |

Assists the primary care provider with direct patient care, and is responsible for patient flow on the day of a visit, including pre-visit planning and visit and room preparation. |

1.0 FTE per panel |

Social Health Support/Community Health Worker (CHW) |

Helps identify needs and connect patients to social health services. |

0.50 FTE per panel |

Behavioral Health Specialist |

Provides day-to-day support for care team and patients with behavioral health needs in close partnership with behavioral health providers on the expanded care team. |

0.50 FTE per panel |

Together, this core care team is the primary healthcare partner for patients and families. They provide the proactive, planned delivery of in-person and virtual primary care for a defined panel of patients based upon evidence-based clinical judgment, patient needs and preferences, and health equity considerations. Core care teams act as the coordinating hub of healthcare services, including physical, social and mental health care needs. Each individual role is described below.

Primary Care Provider (PCP)

- A primary care provider provides direct patient care, and leads and works collaboratively with the core and expanded care team.

- The PCP can be a medical doctor or osteopathic physician (MD/DO), nurse practitioner (NP) or physician assistant (PA).

- An MD/DO may partner with a nurse practitioner or physician assistant to share a combined panel where the MD/DO manages more of the clinically complex care.

- The index model recommends an average panel size of approximately 1,250 patients for each PCP.

- Panel size may shift up or down based on the specific needs and characteristics of a CHC’s patient population.

Medical Assistant (MA)

- At a minimum, the medical assistant’s role is to facilitate the flow of a patient visit, including vital sign measurements, rooming, discharging and providing after-visit summaries.

- MAs also assist with pre-visit planning, complete overdue health maintenance or open orders, ensure screenings are completed and documented, and facilitate follow-up after the visit.

- MAs can also participate in quality improvement, lead team huddles and conduct outreach to patients. The “teamlet” model emphasizes the role of MAs as health coaches.[16]

- Innovative practices point to enhancing the MA role as a key step in improving team-based care.[17]

Social Health Support/Community Health Worker (CHW)

- A community health worker serves as a community resource specialist under the supervision of a licensed provider.

- In accordance with the Plan of Care, CHWs link patients to both community-based organizations and other local services to address health-related social needs, like transportation, housing and food insecurity.

- CHWs can systematically identify social needs through routine screening during visits via questionnaires or empathic conversations.

- CHWs can also advance health equity by understanding and responding to root causes of poor health, and supporting teams to develop culturally responsive practices.[18]

- There is increasing interest in this role due to its inclusion in Cal-AIM.

Behavioral Health Specialist

- Up to 75% of primary care visits include mental or behavioral health components,[19] including behavioral factors related to chronic disease management, mental health issues, substance use, smoking or other tobacco use, and the impact of stress, diet and exercise on health.

- This role is usually filled by a licensed clinical social worker (LCSW) or marriage and family therapist (MFT).

- The LCSW or MFT offers brief interventions for common behavioral health challenges using evidence-based techniques, such as behavioral activation, problem-solving and motivational interviewing. This role supports and coordinates behavioral, mental and substance use treatment with the care team, including behavioral health consultants (psychologist, psychiatrist or psychiatric mental health nurse practitioner).

- Performs patient screening, assessment and testing, and diagnoses and treats mental, emotional and behavioral disorders.

Ideally, people are connected to both community health workers and behavioral health specialists by a warm handoff from another member of the care team with whom the patient has a relationship. During the warm handoff, the patient (and family, if present) are introduced, and some basic information about the patient’s goals and concerns may be shared. Using warm handoffs may decrease stigma and increase utilization of both behavioral and social health services.[20]

Though we suggest licensure and degrees for some of the roles above, a changing reimbursement and certification landscape means there may be many other kinds of skills and training that practices use to address patients’ needs. In particular, peers and certified peer support specialists can play an important role in both social and behavioral health support. Certified peer support specialists are individuals with lived experience with the process of recovery from mental illness, substance use disorder or both, either as a consumer of these services or as the parent or family member of the consumer. California approved a Medi-Cal Peer Support Specialist Certification Program through California Mental Health Services Authority (CalMHSA).

3. Establish a meeting cadence.

Once you’ve understood the needs of the patient panel and assembled a core care team, it is time to create a meeting cadence to begin the hard work of building relationships, problem-solving and managing care together. Like it or not, work gets done through meetings and it is extremely difficult to support team-based care without an opportunity to connect together. High performing teams often have a cadence of daily, weekly and monthly meetings, each with different purposes. Below is a sample of how a team might approach meeting cadence.

FIGURE 3: EXAMPLE CARE TEAM MEETING CADENCE

Meeting |

Cadence/Duration |

Attendees |

Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

Team Huddle |

Daily, five minutes Daily, 10 minutes |

All clinic Core care teams |

Identify issues for the day and big picture. Review patient list and scrub for care gaps or other opportunities to address patient needs while in clinic. |

All Team |

Weekly, 30 minutes |

Core and expanded care team |

Ice breaker. Review weekly huddle tracker. Identify follow-up opportunities and chances to proactively problem solve. |

Quality Improvement |

Monthly, one hour |

Designated core and expanded care team members with quality improvement support |

Review monthly clinical and operational performance measures on patient panel. Identify small tests of change to close gaps and improve patient care or experience. |

To make the best use of meeting time together, it is worth investing in building meeting skills, including identifying a meeting facilitator (this role can rotate), setting agendas, starting and ending on time, facilitating engagement from all participants, and leaving with an action plan.

As you begin working together as a team, you’ll start to see opportunities for ways to shift work and improve information and workflows. The Supporting Change section below has more ideas and tools to help.

Key Activity #2: Identify gaps in staffing and decide how to address them.

After you have understood your patients’ needs and developed a core team that meets regularly, you’re ready to build your expanded care team. Like the core care team, these expanded care teams are ideally linked to specific patient panels and support defined core care teams, prioritizing the ability to build and maintain relationships over time. It may be that your organization has many of these staff in place, and creating your teams requires retraining and reorganization. For some, it may require a decision to hire additional staff.

1. Prioritize expanded care team functions.

High performing primary care functions that are often covered by expanded care team members are described below. Index staffing for the expanded care team, along with expanded care team member duties and recommended education and licensure, can provide a starting place for considering a full care team array.

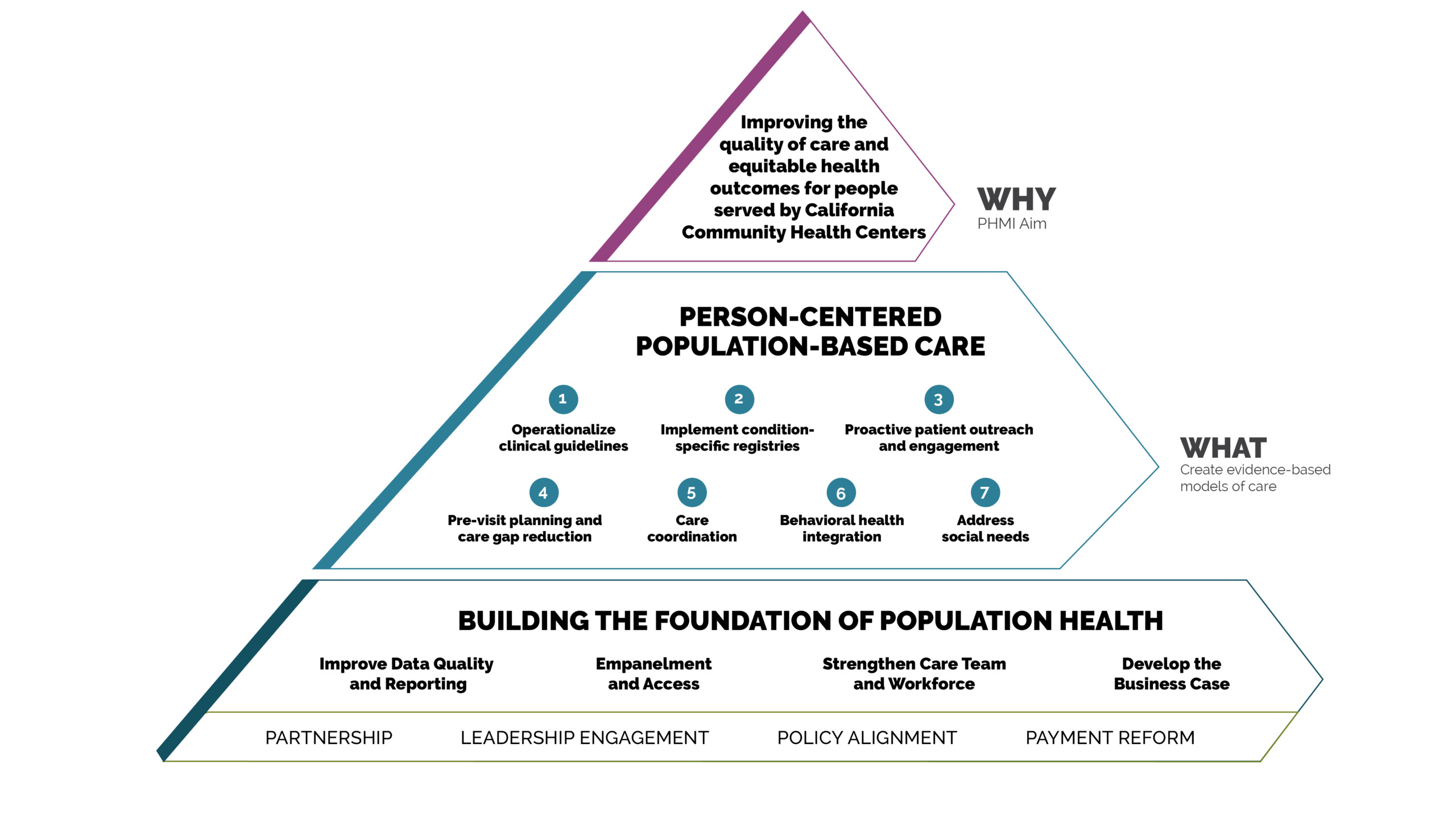

Population Health Management

Population health management is the “process of improving clinical health outcomes of a defined group of individuals through improved care coordination and patient engagement supported by appropriate financial and care models.”[21] The Population Health Management Initiative (PHMI) is designed to support all aspects of this work, from defining a group of individuals (empanelment) to financial and care models (patient-centered population-based care for populations of focus).

For the purposes of care team development, important population health roles on the expanded team assure that patients receive planned services (e.g., routine childhood vaccinations, colorectal cancer screening, HbA1c testing for patients with diabetes). The panel manager and population health specialists roles work together to right-size panels, run care gap reports, and conduct proactive outreach to patients to close gaps in care. Their work can span across multiple panels.

California’s Comprehensive Quality Strategy strives to improve the quality of healthcare and services provided by all Medicaid managed care entities in the state. There are several population management functions anchored by the expanded care team, including:

- Initial and ongoing assurance that patients are empaneled appropriately and connected to needed services.

- Outreach for patients who have not yet established care but have been assigned to the practice by a managed care plan, as well as established patients with care gaps for preventive or chronic disease management services.

Access

Creating excellent access to care is an ongoing challenge for busy practices in communities where there are more people who need care than resources and staffing available. Long waits for appointments not only cause potential delays in diagnosis and treatment, but also undermine patient satisfaction and perceptions of the quality of treatment given.[22] Virtual and after-hours care can help expand access to people with transportation challenges and other daytime conflicts. Managing supply and demand through a systematic empanelment process is another way practices can get a handle on access. Finally, having nursing staff on the expanded care team focus on addressing immediate care needs in person or on the phone, where appropriate, and triage when needed to help the core care teams to manage the needs of their patient panels.

Behavioral Health Integration

Integrating behavioral health into primary care is helpful for expanding access to behavioral health services. The goal of integrated care is to equip the primary care team with effective tools for diagnosis and treatment so people can be cared for holistically by those with whom they have established relationships.[23] Using a structured, team-based approach to behavioral health integration can ease the stigma for some seeking behavioral health treatment, and has been shown to improve depression scores and improve patient and physician experience.[24][25] Studies have also demonstrated cost savings from lower rates of emergency department visits.[26]

Yet, many primary care teams would like more support to manage patients’ complex mental health or substance use disorders. Consulting behavioral health providers, including clinical psychologists, psychiatrists and psychiatric mental health nurse practitioners (PMHNP), can support primary care providers in diagnosing and treating mental health and substance use disorders, including pharmacologic management. They may serve as consultants to the primary care provider, who continues to manage care for the patient, or they may provide direct services to patients, depending on their capacity, patient complexity and staffing priorities. These consulting behavioral health providers work closely with the core care team, particularly to support the behavioral health specialists in addressing routine and lower acuity behavioral health needs.

The collaborative care model (CoCM) is an evidence-based approach to treating common mental health conditions in primary care, which incorporates measurement-based care principles, systematic follow-up, and a team-based approach to supporting patients with persistent mental health challenges.[27] Based on the principles of effective chronic illness care, the collaborative care model focuses on defined patient populations tracked in a registry, measurement-based practice, and treatment to target. Trained primary care providers and embedded behavioral health professionals provide medication and psychosocial treatments, supported by regular psychiatric case consultation and treatment adjustment for patients who are not improving as expected.

More than 90 randomized controlled trials and several meta-analyses have shown the CoCM to be more effective than usual care for patients with depression, anxiety and other behavioral health conditions. CoCM is also shown to be highly effective in treating comorbid mental health and physical conditions, such as cancer, diabetes and HIV. There is strong evidence for use of the collaborative care model as an evidence-based approach to management of patients with depression. To learn more about CoCM, visit the AIMS Center Collaborative Care Implementation Guide.

Medication Management

Comprehensive medication management (CMM) is a patient-centered approach to optimizing medication use and improving patient health outcomes. It is delivered by a clinical pharmacist working in collaboration with the patient and their care team. CMM uses a process in which the patient’s medications—including prescription, nonprescription, alternative, traditional, vitamins or nutritional supplements—are individually assessed to determine that each medication has an appropriate indication; is effective for the clinical condition and for achieving defined patient and clinical goals; is safe in the context of the patient’s potential comorbidities; can be taken by the patient as intended; and adheres to the prescribed regimen.[28]

Studies have shown that CMM produces:

- Improved diabetes outcomes.

- Improved hypertension control and lowered lipids.

- Reduced provider workload.[29]

- Reduced hospital admissions.

- Improved patient experience.[30]

- A financial return on investment as high as 12-131[31] with an average of 3-1 to 5-1.[32]

However, under the current prospective payment system (PPS) fee-for-service model, these positions are not billable for health centers. Practices may choose not to include this function at all, identify a different revenue source, or outsource part of this function (e.g., managing refills or other consultations). Alternatively, fulfilling this crucial function could be an opportunity when considering a capitated payment model.

Care Coordination, Health Education and Care Management

Care Coordination: Care coordination involves deliberately organizing patient care activities and sharing information among all the participants concerned with the patient’s care to achieve safer and more effective care.[33] The Institute of Medicine identifies care coordination as a key strategy to improve the effectiveness, safety and efficiency of the healthcare system.[34] Assisting patients with referrals to other care providers or resources in the community, supporting appointment scheduling and follow-up, and ensuring adequate information exchange between primary care providers and specialists supports safe, appropriate and effective care for patients who may otherwise suffer from the fragmentation in the healthcare system. As with other key functions, Care Teams and Workforce Resource 2: Care Team Duties and Recommended Education and Licensure offers examples of roles to fulfill these functions, but the unique staffing needs, priorities and resources differ at each practice, and some more clerical care coordination functions may be outsourced to a third-party organization.

Self-Management Support and Health Education

Self-management support provides patients with the skills and confidence needed to manage their health day to day. Health education is a part of self-management support, as is building confidence and supporting goal setting and action planning. Self-management support can help and inspire people to learn more about their conditions, and to take an active role in their healthcare.[35] There are many ways to approach offering self-management support and health education, from durable tools such as videos or health plan resources to a centralized or third-party group that specializes in this aspect of care.

Care Management

Care management is a team-based, person-centered and comprehensive approach designed to assist high or rising risk patients and their support systems in managing medical, social and behavioral health conditions more effectively. Care managers offer or oversee care coordination and health education activities, and provide higher intensity services to engage patients in goal setting and self-management support to improve their health.

It is important to note that the care manager is not intended to provide care management for patients with complex circumstances. That role would be provided by a complex care manager and is not included in this care team model, however it is covered through the Department of Health Care Services Enhanced Care Management (ECM) benefit.

Instead, care managers can focus on rising risk patients who comprise 20% of an average panel.[36] Rising risk patients are those individuals with poorly controlled chronic physical and behavioral health conditions or complex social needs who are at increasing risk for poor long-term outcomes or acute health events, such as emergency department visits and inpatient hospitalizations. The rising risk patient population can be further stratified by risk, and practices may choose to select a tool, such as the Milliman Advanced Risk Adjusters (MARA) rising risk model, to more precisely and proactively identify patients for early intervention and care management to make appropriate and efficient use of limited resources.[37]

Quality Improvement

Paul Batalden, a physician, writer and quality improvement expert, once said, “In healthcare, everyone has two jobs: to do your work and to improve it.” As important as it is to provide the functions of high-performing primary care described above, so, too, is creating the infrastructure and staff support to continuously improve it. Expanded care teams need clinical quality improvement leads and support for data analysis to monitor performance measures, create reports, track progress and work with teams to improve patient care. More detail is available on how to set this up in Key Activity #4.

Meeting Language Needs

Communicating with patients and families in their preferred language is vital to person-centered and family-centered care, and for creating trusting relationships between care teams and diverse patients, families and caregivers. Language barriers are associated with lower quality of care, poor clinical outcomes, longer hospital stays and higher rates of hospital readmissions.[38] Cultural humility and linguistic proficiency enables the core and expanded care team to help patients, families and caregivers navigate the healthcare system with safe and timely access to needed services.

Language concordance between providers and patients has been shown to improve care through fewer medical errors, increased understanding of illness and the treatment plan, adherence to the treatment plan, and satisfaction with care.[39] More about language concordance is in the Advancing Health Equity section below.

If language concordance is not possible, practices can develop strategies for ensuring the provision of appropriate interpretation services, and allow additional time for visits and other outreach efforts, such as phone calls by members of the care team. Interpretation services may be provided either on-site through trained healthcare interpreters, multilingual staff, or machine translation or via remote interpretation. The use of professional interpreters is associated with improved clinical care, raising the quality of clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency to nearly equal to that for patients without language barriers.[40]

Practices can document patients’ preferred languages and communication approaches in the electronic health record (EHR), which can help staff prepare for upcoming visits and understand at a population level what additional services might be useful.

2. Assess and build on current team strengths.

You may be lucky in that your organization has all of this expertise in place already. If so, your task is to think about opportunities to improve what you have created. Looking at clinical measures or your Population Health Management Capabilities Assessment Tool can provide ideas of where to start.

On the other hand, you may find that your teams are missing key roles, or your organization has known gaps. You can use the table below to conduct an inventory of your organization’s current state with regard to delivering the key functions of primary care.

If you find that there are gaps in the functions that are or could be offered, you must choose where and how to add staff. For the purpose of this work, we recommend beginning with improving population health management and quality improvement capacity. As your organization moves forward in selecting and managing a population of focus, it will be really important that your core care team is strong and your expanded care team has some key roles including:

- A panel manager or data analyst who can manage panel sizing, open and close panels, and create gap reports. Approximately one FTE across 10 panels. Strong data analysis skills.

- A population health specialist who conducts proactive outreach to patients, and can work with others to create campaigns for needed preventive screenings. Approximately one FTE across 10 panels. Education and experience comparable to that of a strong medical assistant.

Though critical to population health management, neither of these roles requires specific licensure or certification. You may find that you have staff within your organization who have the relevant skills, expertise and lived experience to be redeployed to these roles. If so, figuring out how best to retrain staff becomes a priority. Upskilling medical assistants and lay health workers is a significant challenge, and one that practices often can’t take on by themselves. Creative partnerships with unions and community colleges have shown some promise.[41] Enterprising groups have stepped into the gap with training programs for specific roles (e.g. National Institute for Medical Assistant Advancement). Helping accelerate workforce training is a goal of the Population Health Management Initiative, and ongoing resources will be developed and shared publicly on the PHMI website.

3. Use the Business Case Tool to help make decisions on hiring.

If you find that you need to recruit externally for new staff roles on the core or expanded care team, there are multiple avenues to explore. Consider recruiting and hiring, soliciting volunteers, partnering with other organizations through shared services arrangements, or outsourcing clerical or transactional functions (e.g. medication refills) to an external organization. The Business Case Guide provides a structured tool to help teams walk through the financial implications and sustainability implications of bringing on new positions and services.

The tool includes consideration of current expected payments from health plans, value-based payment arrangements, such as APM 2.0, and any other funding streams, such as CalAIM or grant programs. Working through this Excel workbook as an interdisciplinary team can help teams integrate financial, clinical and operational perspectives on the value of adding new care team roles, and encourage new ways of organizing care, such as exploring group visits or flipped visits.

If, after working through the Business Case Tool, you decide to recruit, this is a special opportunity to build a workforce that reflects the diversity of your patients. Hiring new care team members can be an opportunity to:

- Consider diversity and equity when hiring to reflect the needs of the community and patient populations served. Build in processes to assure equity in hiring, such as widening recruitment by reaching out to job boards, schools, community-based organizations and training programs that are serving diverse communities.

- Revise recruitment process to emphasize flexibility, effective communication and the desire to work in a team. Consider lived experience or job-related experience working with the community as a job requirement. Hire for these attributes rather than exclusively focusing on specific clinical skills or experience.

- When possible, let the care teams lead the hiring process for new members to ensure compatibility and promote a sense of shared accountability for the team’s performance. The Advancing Equity section of this guide includes additional tools and resources on inclusive hiring.

Key Activity #3: Engage patients.

Patients and families are key members of the care team, and you will want to make sure that any substantive changes to how you are delivering care work for them. Involving patients in your care redesign process can help identify challenges upfront. Communicating the new team arrangement and who to contact will help patients make the most of the new system and resources you’re offering.

1. Include patient perspectives on care team changes.

As your organization works through the activities above, there may be opportunities to solicit patient feedback to guide your decision-making. Patient engagement in practice improvement can range from conversations with folks in the waiting rooms about what you’re working on to formal surveys or focus groups. All health centers have patient-majority boards of directors that can be used to offer feedback on new team structures and workflows, and many other practices may have patient advisory groups that can help provide input. The Patient-Centered Interactions Guide from the Safety Net Medical Home Initiative offers pros and cons to different ways of soliciting patient input, as well as guidance for communicating and engaging patients from diverse social, cultural and linguistic backgrounds.

Critical to your care redesign is assuring that patients know who to contact when they need help. For the benefits of relational continuity to persist, patients need to have a small enough team that they can recognize the core care team members as their partners. Working through questions about how patients access services and team members is a great opportunity for meaningful patient feedback.

2. Communicate care team changes.

Helping patients understand the new care team roles can improve how well the teams function and build trust between the teams, patients and their families. From the Safety Net Medical Home Initiative:[42]

- Practice staff often assume that patients have a shared understanding about appointments, how team members interact and the different roles of medical assistants, nurses and physician assistants. However, these assumptions can be faulty, leading to miscommunication, confusion and mistrust. Patients may not understand what a medical assistant does or why their primary care provider is not taking their blood pressure.

Communication strategies to help patients understand who is on their care team include:

- Verbal introductions from the provider to individual team members.

- Letters for new patients introducing the team.

- New patient orientation programs.

- Care team business cards.

- Waiting room pamphlets with team member names, descriptions and pictures.

- Waiting room bulletin boards or posters describing the care teams.

- Color-coded badges worn by care team members to help patients visually link members of their care team.

- Updates to the practice website, if possible, that reflect care team organization.

Patient communication becomes especially important as your team introduces new functions like social health screening or behavioral health integration, which may include sensitive topics and questions that patients aren’t used to answering in the primary care setting. Explaining why the information is being collected, who has access to it and how the information is used to support improved health and wellbeing is an important part of treating patients with dignity and respect.

Key Activity #4: Leverage teams to lead continuous improvements.

Building capacity for quality improvement into the team through a quality improvement lead and quality data analyst as outlined in Care Team and Workforce Guide Resource 1: Core and Expanded Care Team Functions, Team Members and Roles enables your organization to be ready to take on the work of improving patient-centered population-based care.

1. Recognize care team expertise to identify and solve problems.

The core and expanded primary care teams are the heart of population health management. In partnership with patients, care teams create health through compassionate clinical interactions. Each day, the team sees what is working for them and for patients. As such, they have a unique and powerful perspective for understanding what can be improved and how to improve it. Too often, health systems rely on centralized quality improvement infrastructure with little relationship to the care teams who identify and address operational, clinical or questions related to patient experience. As care teams become established, clarify their roles and workflows, and build trust and communication among one another, they can also start to play a key role in clinical quality improvement.

2. Create a structure, including a time to meet, to optimize team performance and address patients’ needs.

Start by identifying which members of the care team will be regularly engaged in the quality improvement (QI) team. Though everyone has a role to play, identifying representatives from different roles to participate on a defined QI team with regular meeting times and activities can help keep momentum going. Participants on the QI team may attend meetings based on which improvement activities you are undertaking, or may rotate over time. The clinical quality lead and data analyst for the expanded care team will be important roles, as will providers, nurses, front desk staff and others who have interest and ideas in improving operational and clinical activities.

Define shared goals and aims.

When teams define their own clinical improvement goals and aims they are taking the first steps in improving patient health and bolstering their own feelings of agency and empowerment along the way. No matter how high-performing, practices always have an opportunity to improve. Reviewing the metrics described in the Data Quality and Reporting Guide is a good place to start for ideas. Getting crisp by defining specific, measurable, actionable, reasonable and time-bound goals can clarify team priorities and cultivate buy-in.

Try small tests of change.

The QI team may suggest plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles, which involve developing an idea of something to improve, testing a new way of working for a few days with a few patients, collecting data and reflecting on the results, and then modifying actions as necessary. Once several PDSA cycles have been run, you will have a good sense for if and how a larger scale implementation would work in your site. When you’re ready, convene the whole team for staff training when implementing major workflow or protocol changes.

Engage often in training and educational opportunities.

Ideas for improvement may come from the QI team, but they can also bubble up from many other sources. Educational material is provided frequently through conferences, live or virtual training, and via learning collaboratives. As staff learn and try new skills, try these approaches to spreading best practices.

- Have one staff member who attends a conference or webinar report back and teach the materials to others.

- Have staff spend a half-day “shadowing” their counterparts at clinics that have successfully adopted specific team-based population health management practices.

- Create opportunities for regular cross-training of staff in standardized protocols and workflow processes across related job roles to ensure consistent provision of care and thorough documentation.

Use data to regularly assess team progress and performance.

Regularly evaluate team progress and look for opportunities for improvement. Clinical data is a great place to start, and teams can also reflect on patient, provider and staff experience data to generate new ideas to try.

Celebrate your successes by sharing learning with other care teams across the organization and at other practices. If you find something that works, share widely!

- Post run charts and other summaries of performance in a shared area for all staff to review.

- Present at an all-staff meeting at the practice, or in the quality committee across a multisite organization.

- Share at regional or statewide learning collaboratives.

Advancing Equity Through Care Teams and Workforce

Health equity—the principle that each person has an opportunity to be as healthy as possible—is enhanced by improving access to the conditions and resources that support health.[43]

The right care team model can advance equity by ensuring team members have the right skills, composition and understanding of how to address structural barriers to health for their patients. Practices can contribute to improving health and reducing disparities as they build their care teams by:

- Prioritize lived experience during hiring and recruitment. CalAIM’s expanded coverage of community health services may enable practices to recruit staff to do more to understand and address health-related social needs that impact patients.

- This resource center developed by the California Health Care Foundation provides tools, training and in-depth guides to integrate community health workers and promoter workforce to support patients: Advancing California’s Community Health Worker & Promotor Workforce in Medi-Cal.

- This website developed by the University of Washington’s human resources department includes best practices, checklists and pragmatic resources for inclusive hiring: Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion - Inclusive hiring.

- A blog by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement outlines four strategies to overcome resistance to prioritizing inclusive hiring: 4 Ways to Improve Workplace Diversity and Equity Hiring.

Explore racial, ethnic and cultural concordance between providers and patients, as well as sexual orientation and gender identity preferences. These are potentially powerful considerations for improving health. Consider these dynamics when structuring patient panels and care teams.

- This brief by the Urban Institute explains the importance of racial, ethnic and linguistic concordance between patients and providers: Racial, Ethnic, and Language Concordance between Patients and Their Usual Health Care Providers.

- This is a free e-learning program offered by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to improve cultural competence and cultural humility around maternal healthcare: Maternal Health Care.

Think about how power and expertise is shared among staff, providers, patients and their families, including building psychologically safe environments and practicing shared decision-making. Power sharing with community partners also builds stronger partnerships that advance equitable health care.

- This guide created by the ACT Center, a part of Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, provides examples and templates for how to engage patients deeply in quality improvement efforts: Collecting Patient Data: Improving Health Equity in Your Practice.

- This resource guide developed by the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care helps primary care practices advance patient- and family-centered care by providing concrete steps including recruitment and support strategies to effectively partner with patients and families: Advancing the Practice of Patient and Family-Centered Care in Primary Care and Other Ambulatory Settings.

- This document shared by the National Academy of Medicine provides important principles to guide transformative partnerships with local communities: Building Community Power to Achieve Health and Racial Equity: Principles to Guide Transformative Partnerships with Local Communities.

- This brief from the Center for Health Care Strategies shares lessons from seven health care organizations about partnering with patients and communities of color to promote health equity: Engaging Communities of Color to Promote Health Equity: Five Lessons from New York-Based Health Care Organizations.

Support teams’ skills and abilities to address the needs of subpopulations of patients, and attend to their specific care needs and structural barriers to health, including tailoring interventions to address root causes of disparities.

- The National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) has developed the free Health Equity and Social Justice (HESJ) 101 Online Training Series to build knowledge and inform practices on key concepts, principles and applications of health equity: Health Equity and Social Justice.

- This evaluation published by the Association of American Medical Colleges provides a training framework for interprofessional teams on the structural factors that produce health disparities: Structural Competency: Curriculum for Medical Students, Residents, and Interprofessional Teams on the Structural Factors That Produce Health Disparities.

- This case study published by the Safety Net Institute highlights how the Riverside University Health System developed an initiative to train and build skills of their workforce to address diversity, equity and inclusion: Reaching for Health Equity (With Peers) at Riverside University Health System.

- This publication from the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) Health Care provides lessons and clinical best practices for how to improve the care of LGBTQ people of color: Improving Care of LGBTQ People of Color.

Supporting Change

Providing effective population-based primary care requires a shift from provider-centric care towards the provision of care by a multidisciplinary team organized around patients and families as critical members of their own healthcare team.[44] In this paradigm, team members contribute their unique skills and expertise to support whole-person healthcare for a panel of patients. Spreading the work of providing preventive, chronic and acute care across the care team requires each team member to work at the top of their license, and involves reimagining traditional roles and responsibilities.

Because this is not how all or even most practices operate, developing and maintaining a team approach to care requires practices to invest time and resources to:

1. Go deep on who does what.

As you start exploring team roles, you may find there are overlaps or duplications that can be removed or gaps that can be filled. Using a tool like this table below can help clarify who is responsible and accountable for clinical tasks on the core care team. A similar tool can be used to explore how tasks are managed among the expanded care team.

2. Create new workflows.

As clinical team members work differently together, mapping how patients and information move between team members becomes important. This is especially true if your team is adding new services or team members to address behavioral health needs or to screen for social needs, for example. Figuring out when screenings occur, who does them, where the results are entered, and who follows up will likely require workflow development and implementation in your EHR or population health management system. Building these workflows into your EHR enables teams to see what’s working and what’s not, and to bring data to quality improvement meetings to continue to adapt and improve team services.

3. Invest in training.

As responsibilities shift from one person to another and workflows are reimagined, teams must assure staff know how to complete their responsibilities. At a minimum, practices can be transparent about what roles need to have specific demonstrated expertise and provide clinical oversight to ensure that is happening. For example, medical assistants may regularly start to take blood pressure. More broadly, there is significant effort in California and nationally to establish ongoing training for medical assistants and community health workers. Resources on these topics are discussed in On the Horizon section below, and will continue to be developed throughout the Population Health Management Initiative and posted publicly.

4. Make space and time to bolster teamwork, in addition to task work.

Much of the work described above is technical in nature and is where many feel most comfortable working, however high functioning teams need trust and psychological safety to perform at their best. Creative practices have recognized the importance of interpersonal relationships on the teams, making time for relationship building, and considering personalities in addition to skills in creating teams. More information and resources are below in the Going Deeper section below.

In addition to investing time and resources, informal and formal leaders and champions have an important role to play in both the technical aspects of care redesign, like understanding state regulations for scope of practice, as well as softer skills, like fostering a culture of curiosity for how roles can be reimagined. Engaged leadership underlies high performing primary care and drives the success of all transformational efforts, including redesigning care teams. Successful practices mobilize leadership on at least three levels:

- Executive leadership develops and shares a mission-driven strategic vision for change, and makes organizational investments in resourcing the change efforts.

- A clearly designated operational leader with well defined responsibility and authority guides the day-to-day efforts of creating operational change.

- Clinical and care team champions promote change with their peers by bringing attention, enthusiasm and direct experience to the operational change efforts.

As an initial step, organizational leaders should develop and share a clear and compelling vision for change, including an overview of:

- What: Clear explanations of the essential components of core and expanded care teams.

- Why: Alignment between care teams and organizational mission and priorities, for example, creates high functioning teams and provides the foundation for a variety of proactive schedule and panel management practices, such as daily schedule scrubbing and huddling. Alignment can increase productivity through the redesign of clinic workflows, collaborative approaches to care management, and development of new modes of patient access and enable care gap outreach calls to patients with chronic conditions.

- How: Anticipated process, timeline and training implications for creating core and expanded care teams.

Because tackling teams means changing how people see and do their daily work, leaders will need to engage people from multidisciplinary perspectives to share their best thinking, support them to work together to make it even better, and lean in to address concerns as they arise.

Going Deeper

Although the importance of teamwork has been well established in primary care for many years, there is a perennial imperative to improve and deepen teamwork. Effective teamwork in healthcare requires not just professional competence on the part of individual team members, but competence in the knowledge, skills and abilities to function effectively together as a team.[45] For organizations interested in going deeper with team development, there are a variety of evidence-based methods for enhancing teamwork, which can range from addressing intrapersonal and interpersonal team dynamics to enhancing the space in which teams work and collaborate. Organizations may also want to consider a systematic approach to promoting joy in work by addressing the minor daily irritants and larger scale organizational changes that drive team dissatisfaction and burnout.

Before selecting a particular intervention to enhance primary care teamwork, articulate your goals and target audience so that you can select an intervention appropriately. Consider the following four types of evidence-based team development interventions:

1. Team Training

This is a team development intervention that uses a formal curriculum and training approach to enhance team competencies and processes. There are many team training curricula, but for an approach that is specifically designed for enhancing healthcare teamwork, consider the Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety (TeamSTEPPS) program created by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Effective team training is targeted towards identified areas for teamwork development with opportunities to learn new information and skills, as well as opportunities to practice and receive feedback in an environment of psychological safety.

2. Leadership Training

Leadership training can improve both the capabilities of participating leaders, as well as the satisfaction of the people who report to them. Leadership training addresses the knowledge, skills and abilities of professionals to behave effectively in formal leadership roles and to foster desired team outcomes. Like team training, effective leadership training is grounded in identified needs and priority outcomes, and includes a mix of knowledge and skill transfer with an opportunity to practice giving and receiving feedback on new skills and behaviors.

3. Team Building

Team building addresses the ability of team members to effectively resolve the problems they encounter, and generally includes four primary components. These components include goal setting, managing interpersonal relationships, role clarity and problem solving. Team building interventions help teams develop shared mental models with particular effects demonstrated by goal setting and role clarification. Effective team building deepens trust, enabling team members to cope with both uncertainty and vulnerability, which leads to better team coordination and performance. Both team trust and the ability to manage and resolve conflict are critical to effective team functioning. The Institute for Excellence in Health and Social Systems provides training and resources on relational coordination for teams that want additional support.

4. Team Debriefing

This is an approach that facilitates team members to reflect together on a recent experience with an orientation towards learning. Debriefing involves the team discussing the event, identifying issues and improvement opportunities, celebrating successes, and developing a plan for future performance. Team debriefing also promotes shared mental models and clear understanding of team roles and responsibilities, strengths, priorities and challenges. Effective team debriefing requires an environment of trust and psychological safety, a structured and facilitated approach, inclusive conversation, and reflection on both positive and negative aspects of team performance to promote learning and behavior change.[46]

Although evidence-based interventions are available to improve team functioning, difficult organizational conditions will seriously hamper the effectiveness of teams.[47] Many healthcare organizations and workforce members have been under unprecedented stress in recent years, due to the intense challenges and demands of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although many healthcare organizations were already seeking interventions to address employee burnout, the need for enhancing joy in work has only grown.

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) has created a robust framework and set of tools for organizations interested in investing in employee well-being and joy in work. IHI recommends that leaders start with four key steps:

- Ask staff what matters to them.

- Identify unique impediments to joy in work in the local context.

- Commit to a systems approach to making joy in work a shared responsibility at all levels of the organization.

- Use improvement science to test approaches to improving joy in work in your organization.[48]

While improving joy in work can sound like an aspirational goal, systematically addressing the obstacles to employee well-being and engagement are essential for creating the conditions wherein teams can thrive.

In addition to investing in team development and systematic interventions to address burnout, team-based care can be enhanced by effective space design.[49] Although basic team space redesign, such as colocation to improve visibility and communication, can improve team functioning, these interventions have little effect on patient satisfaction.[50] If you are interested in space design that both enhances teamwork and patient experience, consider adopting principles of trauma-informed design to improve your medical office space. Recommendations for trauma-informed space design include:

- Reduce and remove known adverse stimuli and environmental stresses, including flickering lights, ambient noises, odors and visual complexity.

- Create spaces with clear sightlines to promote a feeling of calmness and safety, and avoid the typical maze-like layout of many healthcare settings.

- Seek to actively engage individuals in a dynamic, multisensory environment that relies on cool colors, culturally relevant art and decor, and neat and tidy spaces.

- Support self-reliance with adequate, clear and consistent signage.

- Provide and promote connection to the natural world by incorporating natural light, plants that are easy to care for, and water features, if appropriate.

- Offer both private and social spaces, and create opportunities for separation and privacy for those in distress.

- Reinforce a sense of personal identity and choice with modular furniture that can be rearranged, dimmable light fixtures, and adjustable window coverings.[51][52]

The adoption of a trauma-informed approach has to include consideration of the workforce experience and wellbeing. Investing in trauma-informed team space design can promote psychological and physical safety and calm for staff, as well as patients.

Voices From the Field

Brian Park, M.D.

Dr. Brian Park is a family medicine provider at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) Family Medicine at Richmond. Dr. Park is passionate about creating a more relational and inclusive health system for patients and communities by bringing diverse communities together to create systems and social change. He founded and oversees a community organizing program in which patients, healthcare providers and community partners come together to create solutions for local health equity issues. He also directs a leadership program in which healthcare students and professionals develop relational leadership skills to better partner with one another to create systems and social change. Dr. Park was born in Minnesota and raised by South Korean immigrant parents. He saw firsthand how language barriers and cultural differences influenced his family’s experiences with the healthcare system. Because of that, from a young age he became interested in how healthcare could advance justice and equity.

Q: What do you regard as the leading edge for primary care teams these days in terms of current challenges and creative solutions?

A: There is more of a collective mainstream awareness of the need to partner with patients and families. In Oregon, there has been such an ongoing emphasis on whole-person care, community health workers (CHWs) in the primary care setting, and in community-based organizations. At Richmond Clinic, the CHWs have really solidified their role in both doing social needs screening and providing assistance to people who screen positive. They are also focused on creating more cultural or racial congruence with families. This allows the providers to focus more on their expertise in medical care and allow the CHWs to focus on those social pieces where they have so much expertise.

I hear from a lot of healthcare leaders about their work on internal culture and the need to respond to mass burnout and people leaving the workforce. This is about going beyond being adequately staffed, but really about creating places of belonging for people of color working in primary care, as well as getting back to the roots of community health and truly being a community health center. It’s not just about the things we do in terms of our services, but about the culture and adaptive reserve that we create within our teams.

People seem more aware of the importance of things they saw as soft skills before. In my work with the Relational Leadership Institute, we are getting a lot of requests for team building and relationship building work, maybe from people who don’t even really understand it. We are focusing on readiness and ensuring that there will be a good chance of adoption, and not just grasping at a quick fix. The relational approach can help address conflicts or gaps between members of an interdisciplinary team; for example, medical and behavioral health providers. There has been a subtle but notable shift in the culture, recognizing that relationality may be a soft skill, but it is still foundational.

Q: What are you currently focused on in terms of equity-focused innovations in primary care? How is it going?

A: The rise of digital health and the understanding of its capabilities has been substantial. The first big wave of digital health with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic really introduced so much more access to primary care by reducing transportation barriers and the obstacles to coming in. Now, we are really learning about how digital health imposes its own obstacles and has serious health equity implications. Some culturally specific groups really want face-to-face care, and they will travel an hour for it because they want to be in the room with the provider and to be touched physically by them. Even if there are transportation challenges, they may still want to do that. I am involved in a project with a culturally specific organization trying to use human-centered design to understand what digital health means to them and what they want out of it. Some of the things that we’ve learned about are obvious, like having MyChart in more languages than English, but then on the less obvious side, we are elevating youth as digital experts and leaders who can help their elders with bridging the digital divide. Recreating the fabric of connection across generations is important in many cultures, and with this approach we can do both.

Then, there are other groups who just want face-to-face care, so some of the community organizations are doing in-person teaching on digital tools for people who might be hesitant about going digital, but really need that kind of access. They are trying to be very intentional about their process to share power, offer resources, uphold lived expertise, and really try to create these spaces where solutions are co-designed.

We are working hard to build a health equity organization, and to ensure that we are putting communities at the center, slowing down, creating trust and partnership, and letting the strategy emerge from there. We are really focused on community-partnered or community-led work where healthcare is providing resources or social capital, but community is leading the way.

Some of the biggest things that have happened in our community organizing work is recently wrapping up a two-month civic engagement project, taught all in Spanish, to 23 Latinx people with mixed immigration status. Those people are feeling really empowered, and they are planning to host a health justice summit later in the summer. This was really consequential to actually building power for these people and the confidence to exercise it.

We have also been organizing justice-involved folks to address care gaps because of the enormous elevated risk of death in the first 30 days after release from imprisonment. We are trying to focus on knowing when people will be released, ensure that they are enrolled on the Oregon Health Plan, and connecting them to primary care and medication-assisted treatment, if they need it. We are working on this with a core team of folks with lived experience with this issue.

Q: What interesting things are happening in your practice that go beyond the walls of the clinic?

A: We are working on accessing pockets of money that are assigned for community benefit or community partnerships, but then fall short by centering the healthcare delivery system. We are really trying to create longer-range thinking and investment, and trying to radically reorient healthcare around people, place and power.

We just got funding to geomap all of the patients at our clinic and stratify the population using race, ethnicity and language (REAL) data. We saw even greater inequities within certain neighborhoods that emphasize the impact not just of individual characteristics, but also community or neighborhood characteristics. With this information, we are going to focus on two neighborhoods in east Portland and do quality improvement to improve care processes for people of color with diabetes, including how we deploy panel managers, clinical pharmacists, CHWs and other members of the care team. We are going to have CHWs focus on social screening and assistance, as well as organize people within their neighborhoods on what factors impact their health in their area and what can be done to improve the health of their place. We hope to create a process blueprint for how to both improve medical processes, but also partner with people to improve the health of their community.

Jillian Robinette, MBA

Jillian Robinette serves as the director of The Learning Well, a new La Clinica service that provides whole-person health education, workforce development and support with the goal of making total wellness accessible to every member of the community. Jillian previously served as a practice manager at La Clinica’s Wellness Center, Acute Care Clinic, and Birch Grove Health Center, and provided behavioral health support for the organization. She has been with La Clinica since 2011.

Q: How has La Clinica approached designing trauma-informed and patient-centered spaces for people to connect with their primary care teams?

A: Primary care clinics are often very maze-like. We use rounded corners and clear sightlines as much as possible to help people feel safe. At La Clinica, we wanted to create suites and pods that communicate to the patient who their team is, and that starts at the front desk. We created sliding doors from the reception space into the team room so that there was immediate access but no violation of privacy.

Q: What do you think is most important for designing spaces to effectively support primary care teams?

A: Good team-based care requires creating an environment where you are sitting together doing your work in a way that is compliant and respectful to the patient’s care and people sitting around you, as well as pulling in others who are relevant to the care. For example, the receptionist is the first point of contact for care and needs to have a pathway to being part of the team, but not part of every conversation clinically. You can co-locate all kinds of things, but that can end up feeling really overwhelming to staff.

We have embedded pharmacies now, and specifically put the pharmacy in a centrally located space in the building so that it is both accessible to all within, but also available to the public who might not use the clinic. We have a pharmacy consultation room, and the providers can walk the patient to that space and have a collaborative conversation with the pharmacist to ensure that the patient is well set up with their meds. We also have a centrally located lab station in the wellness center that serves all three suites. Rather than sending the patient on a hunt for that spot, we set up the workflows so that the lab tech can come to them, and or we create sample stations within the suites.

We set up our suites so that the team is not distant from the exam room. When you have a colocated space, the team room is sometimes far away from the exam rooms, and that leaves the provider without much team support, and then it just ends up still being a provider-specific model. We created the corridors to be a large circle with three suites wrapping around the exam rooms so that they have close and direct access from the team rooms to the exam rooms. As the provider is walking the patient out, they are walking by the team room and making visual contact with whoever is there so that they can do a warm handoff or introduction right in the moment in a very opportunistic way.

We have also done a lot of work to embed some of the alternative treatment rooms within the design of the traditional primary care rooms; for example, a small group room and consultation room that is embedded near the primary care rooms. They are fully a part of the care team and embedded together, not just an alternative tacked alongside.

We are always thinking about how to make it more user-friendly for the staff as well as the patients. We had to do a lot of lean process improvement to make this work because when we started by just designing for the patients, it created extra steps for the staff. We really had to work together to figure out how to make it better for everyone so that it wasn’t exhausting for the staff because you can’t provide good care when you’re exhausted. You have to stick with it and listen to the people doing the work.

Another important element is to use space design to keep all the work flowing in the right direction. We use a visual display board to show works in progress, quality metrics, and panel-level performance, and focus on the small numbers of people who are being cared for by the team and where they can make a difference in people’s lives.

Q: What do you think is important for building physical spaces that support health equity?

A: We are currently going for a health equity accreditation. and are really looking closely at our spaces and especially thinking about signage. We are seeing opportunities to improve how inclusive our signage is for wayfinding and to communicate belonging. Instead of asking people to rely on written signs, we want to be able to say, follow the orange signs or the arrows out. We are trying to use pictures of the people we serve, not just stock photos. We are improving the signage at the front door regarding what languages we speak or can interpret so that people know what to expect before even coming in.

On the Horizon

In response to the evidence that healthcare has a relatively narrow effect on health outcomes in comparison to social and structural factors, there has been an explosion of interest in broadening the provisions of primary care from the traditional approach inside the walls of a clinic to a more expansive, collaborative and community-based model.[53] Expanding primary care outside the walls of the clinic can include a range of strategies, including: