©️ 2024 Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, Inc.

This guide provides step-by-step guidance for improving population-based care for adults living with chronic conditions with the goal of supporting substantive cultural, technological and process changes. In particular, it focuses on increasing the number of patients who have controlled high blood pressure and comprehensive diabetes care.

This guide was designed as part of the Population Health Management Initiative (PHMI), a California collaboration of the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS), Kaiser Permanente and Community Health Centers. Much of the content is relevant and adaptable to primary care practices of all kinds working to improve the health of the populations they serve.

It is estimated that six in 10 U.S. adults are living with a chronic disease, and chronic diseases are the leading cause of death and disability in the United States[1]. The impact of chronic conditions and the rates of complications are higher in historically marginalized populations[2]. One of the most effective ways to manage chronic diseases and reduce health inequities is by applying a systematic, team-based care approach to wellness visits for chronic disease screening and to subsequent scheduled visits for management. Adopting standard procedures to identify and manage chronic conditions allows practices to provide high-quality, person-centered, culturally responsive care to patients, foster efficiency, and reduce clinician and staff burden. Systematic care that incorporates a person-centered approach to managing chronic conditions improves equity in care and patient outcomes by:

- Improving health and well-being among all patient populations.

- Recognizing and reducing potential barriers to care.

- Reducing burnout among clinicians and staff.

The work to ensure that patients have access to high-quality, person-centered diabetes and hypertension care is a continuous effort, and we still have much to learn. This “living” document uses existing evidence, bright spots and examples from the field to offer practical guidance on improving the effectiveness of your diabetes and hypertension management protocols while ensuring patient access to preventive care. While some of the guidance in this document is technical, much of the guide is focused on supporting practices in the substantive cultural, technological and process changes that lead to improved population-based care for adults with diabetes and/or hypertension. Virtually every activity in the guide will require some level of adaptation for your practice’s unique context. The Population Health Management Initiative (PHMI) will update this guide as we learn from and with practices.

We have organized the key activities in this guide into three categories:

- Foundational activities: Activities that all practices should implement as part of the activities to support the two core measures (Comprehensive Diabetes Care and Controlling High Blood Pressure) and the supplemental measure (Adults’ Access to Preventive and Ambulatory Health Services).

- Going deeper activities: More advanced activities that build off the foundational activities and that help ensure your practice can achieve equitable improvement in your patients’ management of chronic diseases, including diabetes and hypertension.

- On the horizon activities: Additional activities, including ideas worthy of testing that include the latest ideas and thinking on management of chronic diseases, including diabetes and hypertension.

Sequencing activities: We recommend that practices consider planning and attempting to implement the activities in the sequence provided in this guide. At the same time, we recognize that different practices may follow a different path toward prioritizing and implementing these activities. Furthermore, there is a lot of overlap between activities; many activities build off, or form the building blocks, of other activities.

Testing and implementing: For each activity, we provide guidance on how to plan, test and implement the activity along with links to other resources, Technology considerations and examples. Consider testing different versions of the action steps and roles on a small scale before fully implementing them at your practice.

Maintaining progress: For many activities, we also provide tips for periodically reviewing and making improvements to key workflows after initially implementing the change. Ongoing review and continual improvement are important for your practice to maintain your progress in population health management and to help you stay nimble in adapting to changing patient demographics, new clinical best practices, new payment policies, workforce changes and other changes at your practice.

If you implement the Foundational Activities in this guide, your practice should be able to achieve the following foundational competencies.

For chronic conditions, your practice will be able to consistently:

- Engage patients served by your practice to validate any of your proposed process improvements and to propose alternative methods to improve quality in your focus area.

- Analyze core quality measures to identify inequities and opportunities for improving A1c control and blood pressure among attributed patients.

- Implement chronic care management activities.

- Create an outreach protocol to reach and engage all attributed patients due for care.

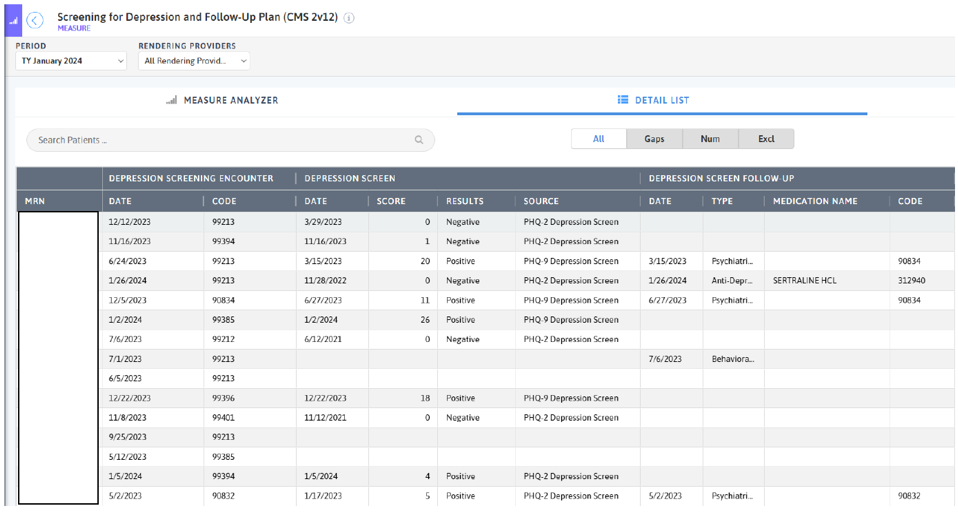

- Integrate behavioral health follow-up services as needed (e.g., for positive depression screens).

- Create a health-related social needs screening process that informs patients’ treatment plans.

- Assess current capabilities and develop a plan for ongoing improvement in data utilization, care team workflows and efficiency that includes sustainable health information technology (HIT) strategies and continuous staff training on technology.

This guide also includes sections on measurement, equity, social health, and behavioral health integration as well as an appendix with helpful tools and resources. We have included information about California Medi-Cal-covered benefits and services that were up-to-date at the time of publishing, but benefits and billing guidance change over time. Nothing in this guide should be considered formal guidance. Anyone using this guide should check with the appropriate authorities on benefits and billing guidance. This document will be refined based on continued learning on this topic; future updates may include additional activities, examples, resources and sections.

Working to improve the health of a population leverages everyone in a practice. Critical roles needed to engage in the work outlined in this guide and support practice change include:

- Quality improvement (QI) leadership, like a QI director, or additional team leads (i.e., clinical, front office, etc.) to support cultural changes.

- Coaches or practice facilitators who are partnered with teams to help identify areas for improvement and support change through change management strategies.

Putting the Key Activities in Context

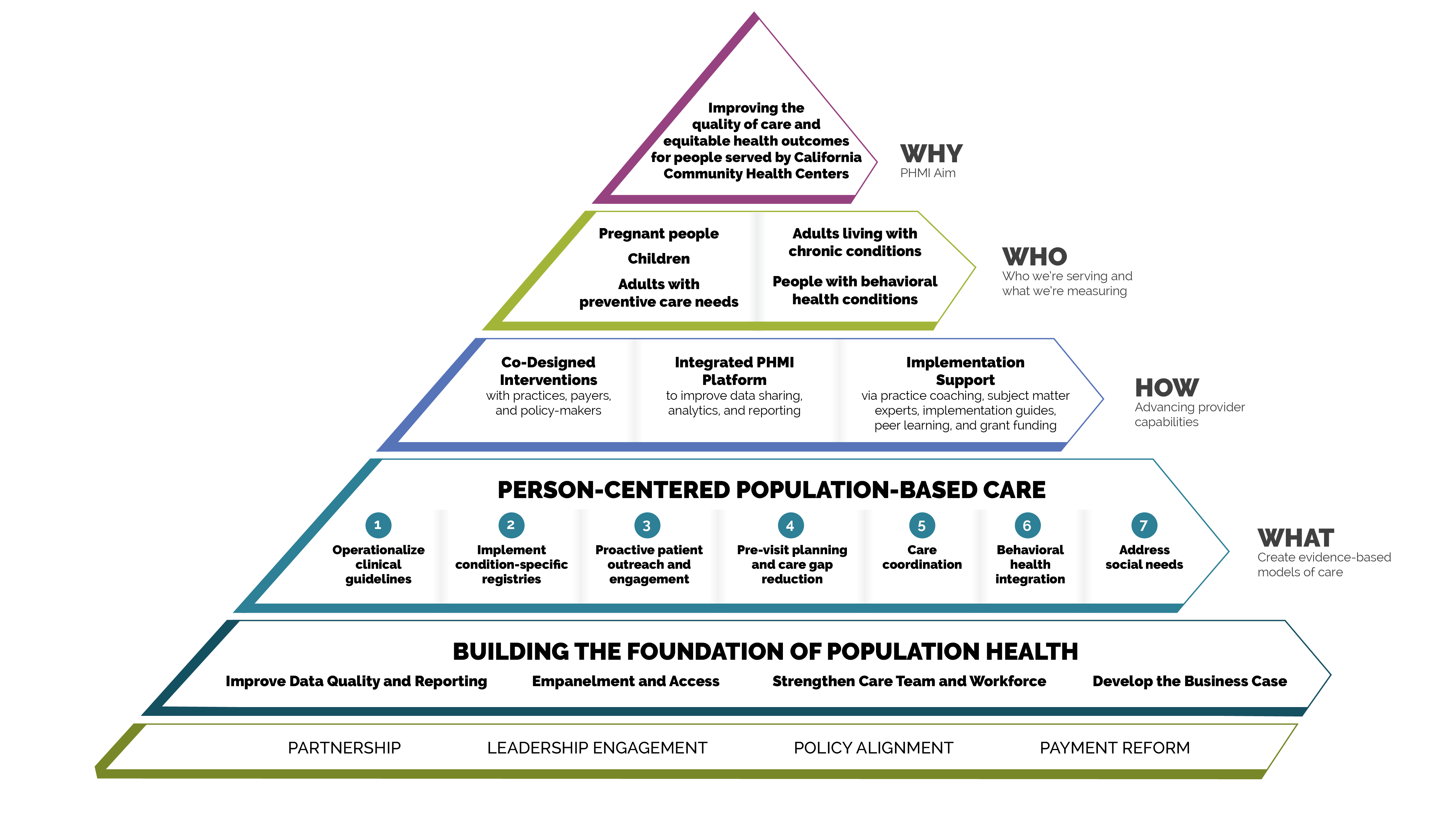

Person-centered population-based care

Each of the key activities advance one or more of the seven person-centered population-based care change concepts:

- Operationalize clinical guidelines.

- Implement condition-specific registries.

- Proactive patient outreach and engagement.

- Pre-visit planning and care gap reduction.

- Care coordination.

- Behavioral health integration.

- Address social needs.

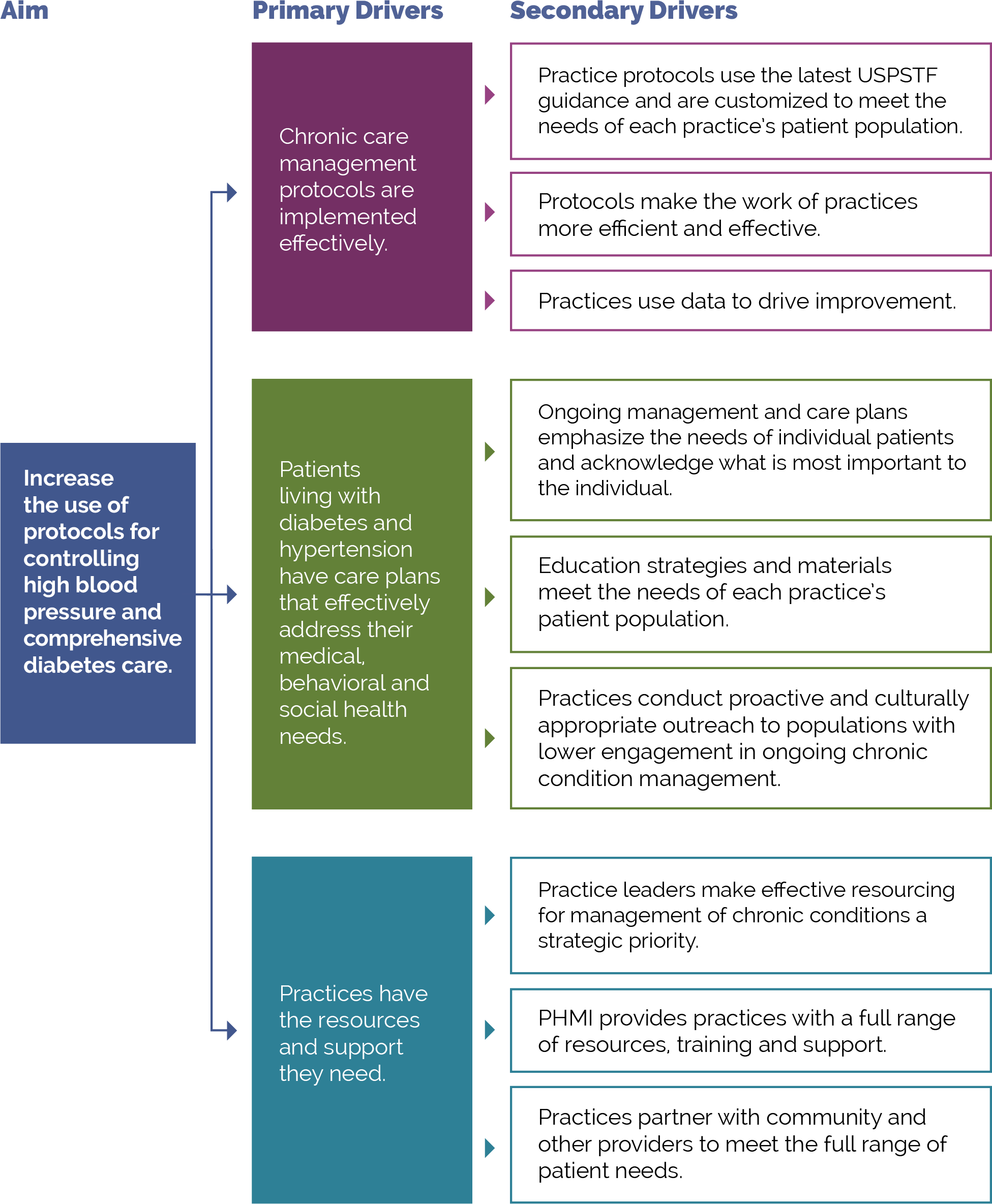

FIGURE 1: PHMI IMPLEMENTATION MODEL

The measures covered in this guide consist of Healthcare Effective Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures designated as core and supplemental measures by PHMI. These measures can be considered outcome measures because there is ample evidence that improved timely screening rates and follow-up care improves overall population health outcomes for depression. All measures use standard HEDIS definitions and are aligned with California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Ca (CalAIM) and Alternative Payment Methodology (APM 2.0). For information about these measures, reference the PHMI Data Quality and Reporting Guide

PHMI selected two core and one supplemental measures of focus for adult chronic condition management, though practices can track others that feel important and relevant. This guide provides detailed guidance to improve your practice’s results on the measures selected by PHMI.

Core HEDIS Measures for PHMI

|

PHMI Populations of Focus |

Measures |

|---|---|

Adults Living With Chronic Conditions |

Controlling High Blood Pressure

|

|

Comprehensive Diabetes Care

|

Supplemental HEDIS Measures for PHMI

|

PHMI Populations of Focus |

Measures |

|---|---|

All Adults |

Adults’ Access to Preventive and Ambulatory Health Services

|

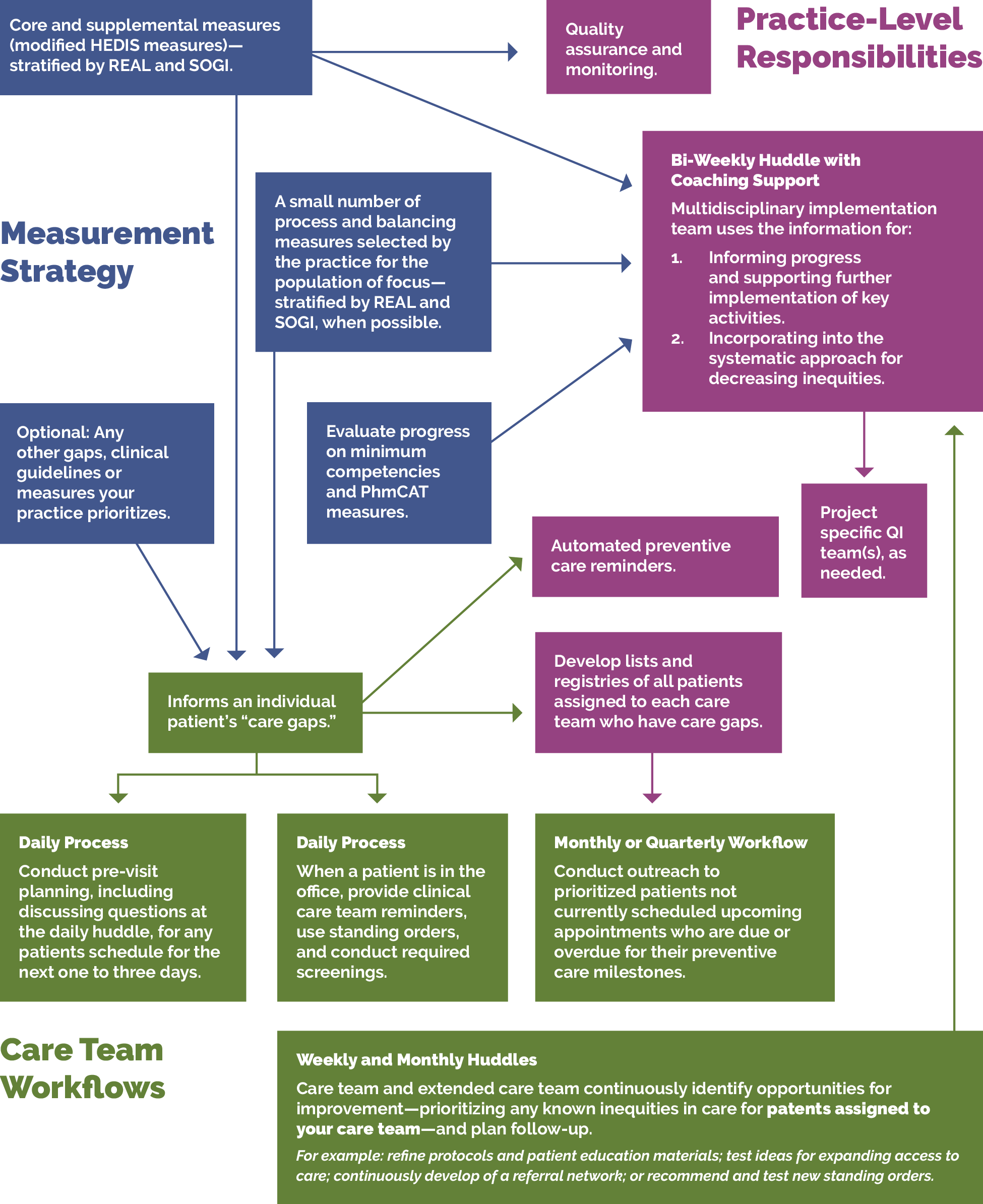

The core and supplemental measures are part of a larger measurement strategy and learning system, as outlined in Appendix A: Sample Idealized System Diagram: Weaving Your Measurement Strategy and Learning System into Practice Operations. Key Activity 1: Convene a Multidisciplinary Implementation Team for Chronic Care Management outlines how your practice can develop a robust measurement system to support this work. In addition to quality assurance and monitoring, measures are also used during practice operations alongside other data for learning to:

- Guide the actions of the multidisciplinary implementation team as it uses a systematic approach to decreasing inequities and support implementing key activities across the practice.

- Support the care team’s efforts to advance population health and reduce care gaps through daily, weekly and monthly workflows, as well as continuously identify opportunities for improvement.

The PHMI Clinical Guidelines Advisory Group (CGAG) was established to create a standardized approach to review, adopt and promote established clinical guidelines in the PHMI cohort. For people with chronic health conditions, guidance includes controlling hypertension and comprehensive diabetes care. For more information please see the PHMI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Key Medi-Cal Populations of Focus.

FIGURE 2: CLINICAL GUIDELINES: CONTROLLING HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE

Guideline source |

Kaiser Permanente National Guideline Program (October 2021) |

PHMI measure |

Controlling High Blood Pressure |

Guideline language |

Blood pressure (BP) screening: Screen adults 18 years and older for high blood pressure.

Hypertension definition:

Treatment initiation:

Treatment target:

For corresponding SBP/DBP values, corresponding SBP/DBP values, initial pharmacotherapy, and follow up recommendations see the PHMI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Key Medi-Cal Populations of Focus.

|

FIGURE 3: CLINICAL GUIDELINES: COMPREHENSIVE DIABETES CARE

Guideline source |

USPSTF, American Diabetes Association (ADA) and Kaiser Permanente National Guideline Program (July 2023) |

PHMI measure |

Comprehensive Diabetes Care |

Guideline language |

Screening (USPSTF): Asymptomatic adults aged 35 to 70 years who have overweight or obesity. Diagnosis (ADA):

OR

OR

OR

For the full ADA guidelines, see Diabetes Care 2. Classification of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes - 2023 For glycemic control and treatment targets, and guidelines for self-monitoring, see the PHMI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Key Medi-Cal Populations of Focus.

|

Many key activities in this guide include considerations for utilizing the intervention to improve equitable health outcomes and reduce the effects of racism, bias and discrimination. Key Activity 4: Use a Systematic Approach to Decrease Inequities Within the Population of Focus describes key action steps for how to make an intentional and explicit effort to identify inequities, understand root causes and reduce those inequities.

This guide also offers resources for going deeper into organizational and ecosystem-level work to advance equitable outcomes through strengthening a culture of equity. More information about this approach can be found in the PHMI Equity Framework and Approach and Key Activity 23: Strengthen a Culture of Equity.

Integrated behavioral health supports are important for adults as effective management of chronic conditions is likely to boost health outcomes and enhance patients' quality of life.

One foundational change is to ensure that the care team includes behavioral health staff as core members of the team; this is covered in detail in the PHMI Care Teams and Workforce Guide.

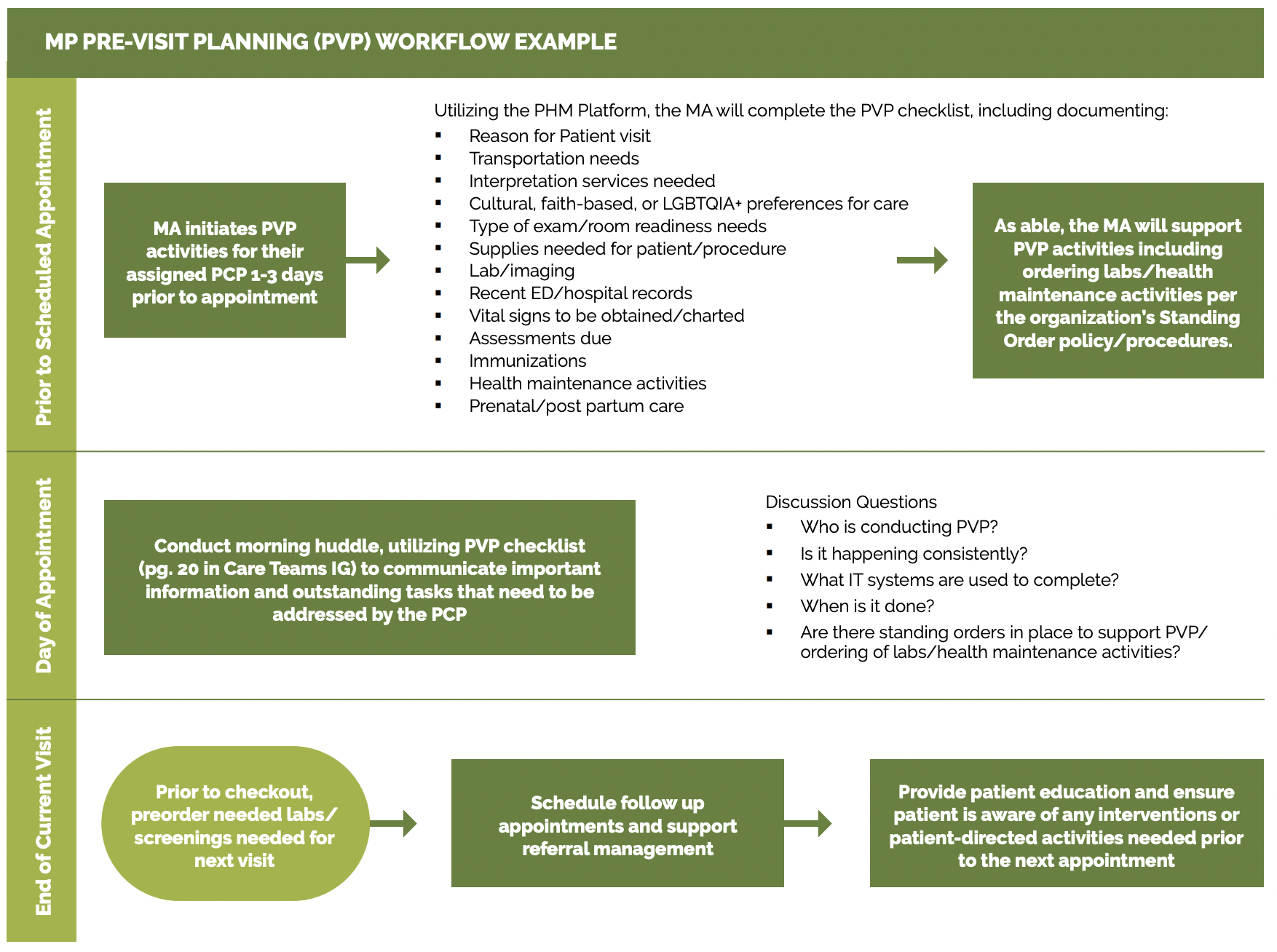

We also offer the resource Pre-Visit Planning: Leveraging the Team to Identify and Address Gaps in Care includes recommended behavioral health screenings.

Throughout the key activities in this guide, we have incorporated considerations for providing trauma-informed care and have included a resource for Trauma-Informed Population Health Management. For additional information, please see the PHMI People with Behavioral Health Conditions Guide. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) also provides resources on integrating health equity and behavioral health.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) recommends that in order to advance health equity, practices and health systems must consider and address health-related social needs that impact their patients.[3]

For many key activities in this guide, we have highlighted considerations related to social needs at an individual or population level, such as expanding clinic hours and coordinating care. Key Activity 17: Use Social Needs Screening to Inform Patient Treatment Plans assists to develop a process to screen for social needs, which can help practices better understand and support patient- and population-level needs. Practices can help patients make connections to resources in the community to address issues such as nutrition and legal and health education needs. For Medi-Cal patients and families with high levels of social need, such as those experiencing homelessness, referrals to Enhanced Care Management (ECM) and Community Supports programs are available; see Key Activity 21: Provide Care Management for more.

To go deeper in this area, practices can further develop their referral relationships and pathways (Key Activity 22: Continue to Develop Referral Relationships and Pathways Networks) for common social needs and strengthen community partnerships (Key Activity 20: Strengthen Community Partnerships) to build upon the strengths, infrastructure, and resources available in the community. More information about this dual patient- and population-level approach is available in the PHMI Social Health Framework and Approach.

Our theory of change is that if practices implement the activities contained in this guide, it will lead to improved health and well-being outcomes among patients with chronic conditions served by these practices. See Appendix B: Theory of Change for a suggested driver diagram.

Foundational Key Activities

These are the core activities that all practices must implement as part of the activities to support the two core measures (Comprehensive Diabetes Care and Controlling High Blood Pressure) and the supplemental measure (Adults’ Access to Preventive and Ambulatory Health Services).

KEY ACTIVITY #1:

Convene a Multidisciplinary Implementation Team for Chronic Care Management

This key activity involves all seven elements of person-centered population-based care: : operationalize clinical guidelines; implement condition-specific registries; proactive patient outreach and engagement; pre-visit planning and care gap reduction; care coordination; behavioral health integration; address social needs.

Overview

This activity provides guidance for senior leaders to identify the right individuals within your practice who will be responsible for planning and implementing the key activities in this guide and overseeing related quality improvement and equity efforts, as outlined in Appendix A: Sample Idealized System Diagram: Weaving Measurement and Learning Into Practice Operations. This section also provides guidance on how to support and sustain this team to foster success.

The implementation team members are a diverse group of individuals who are champions for advancing this work. Improving your practice’s key outcomes for each population of focus and reducing equity gaps require the aligned efforts of all care teams and nearly all functional areas of the practice, not just those working directly with patients.

This team is responsible for ensuring that all foundational key activities in this guide, including those related to screening for social needs, are implemented. When identifying potential members of this multidisciplinary implementation team, the practice should identify a diverse group of staff who are reflective of various job functions within the practice, the local community and, by extension, the lived experience of patients. In addition to implementing Key Activity 4: Use a Systematic Approach to Decrease Inequities Within the Population of Focus, the team should apply an equity lens to every step outlined in this guide to help ensure that any improvements are equitably spread among the patient population. To achieve optimal functioning and impact, all members of this diverse multidisciplinary team should have their perspectives proactively included.

Relevant HIT capabilities to support this activity include care guidelines, registries, clinical decision support, care dashboards and reports, quality reports, outreach and engagement, and care management/care coordination (see Appendix E: Guidance on Technological Interventions). To enable team coordination, thought must be given to how access to relevant technology and how data capture can be distributed, consistent and integrated into workflows, and how data is accessible across team members. Where possible, it is desirable to avoid duplication of data entry, siloing of information in standalone applications and databases, and the need to work in multiple applications that require separate login.

Action steps and roles

1. Convene a time-limited group of practice leaders.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: chief medical officer (or equivalent), office manager or QI coordinator.

Start with a small group of leaders from your practice (some of whom will be on the implementation team) who can help refine the “charge” or scope of work of the implementation team and both identify and engage the people/roles that will be required to implement the scope of work of the team.

2. Develop a preliminary scope of work or charge outlining the responsibilities of the implementation team.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: time-limited group of practice leaders.

This scope or charge includes but may not be limited to enabling, aligning, leveraging and supporting the planning and implementation of all foundational activities in this implementation guide so that the practice meets the foundational competencies for chronic conditions. This should include a tentative timeline, core activities, and key roles and responsibilities.

However, there may be further foundation-building work needed at your practice in order to succeed at the above key activities. The Population Health Management Capabilities Assessment Tool (PhmCAT) is a multidomain assessment that is used to understand current population health management capabilities of primary care practices. This self-administered tool can help your practice identify opportunities and priorities for improvement.

If your practice does not score highly in the domains of leadership and culture, the business case for population health management, technology and data infrastructure, or empanelment and access, consider implementing the activities listed in the four guides on Building the Foundation before or in parallel to working on key activities related to management of chronic conditions.

3. Identify leadership and key actors for the implementation team.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: time-limited group of practice leaders.

The multidisciplinary implementation team should include those empowered to make changes in workflows, policies and staff assignments. They should be respected influencers in the organization (early adopters), who can also guide the change management process. They should include those with expertise in partnering with patients with diabetes and hypertension management.

- Appoint a “champion” or lead person (e.g., chronic conditions care coordinator or diabetes care coordinator) to oversee the implementation and coordination of the team.

- Identify key staff who will be the core members of the implementation team. These people will likely include one or more panel managers, clinicians, nurses, administrators, data analysts, social workers, community health workers, and other community outreach staff, information technology (IT)/electronic health record (EHR)-related personnel, and human resources personnel.

- For the chronic conditions multidisciplinary team, it is important to include members of the clinical team, patient support team, outreach team, social support team and EHR/data team. This could include a core team and an expanded team. Potential members include:

- Adult/family primary care clinicians (medical doctor, doctor of osteopathic medicine, advanced practice registered nurse, physician assistant).

- Endocrinologist.

- Cardiologist.

- Registered dietician.

- Certified diabetes educator.

- Nurse.

- Medical assistant (MA) or licensed vocational nurse (LVN).

- Social worker.

- Care coordinator.

- Community health worker.

- Pharmacist.

- A member of the IT or EHR team (as part of the expanded team).

- QI lead.

- Billing manager or similar (as part of the expanded team).

- A frontline staff member who interfaces with patients by phone and at check-in.

- Invite identified people to become part of the implementation team and ensure that they have appropriately designated time for participation.

- Teams should engage representation from IT to support the work of pulling data from the EHR and embedding updated data into tracking and evaluation.

4. Launch the implementation team and set it up for success.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: clinical coordinator or chief operating officer or chief medical officer.

This work includes:

- Ensuring that the team understands its charge or scope of work by developing a Multidisciplinary Implementation Team Charter Template, that outlines this work. Groups should work with each other to establish rapport and psychological safety as they develop team norms, which help teams to work together effectively.

- Defining roles and responsibilities, including the anticipated commitment (in hours) on a monthly basis.

- Establishing a meeting structure, file structure and communications structure to support effective, efficient work.

- Dedicating time and effort to forming, storming, norming and performing as a team. The Team Communication and Working Styles Template is one tool that team members can complete and share with other teammates to accelerate this process.

- Understanding baseline data related to outcomes of interest (e.g., hypertension control rates, hemoglobin A1c control rates), along with data related to known and perceived barriers to these outcomes.

- Prioritizing elements within the scope of work, informed by baseline data and identified population needs.

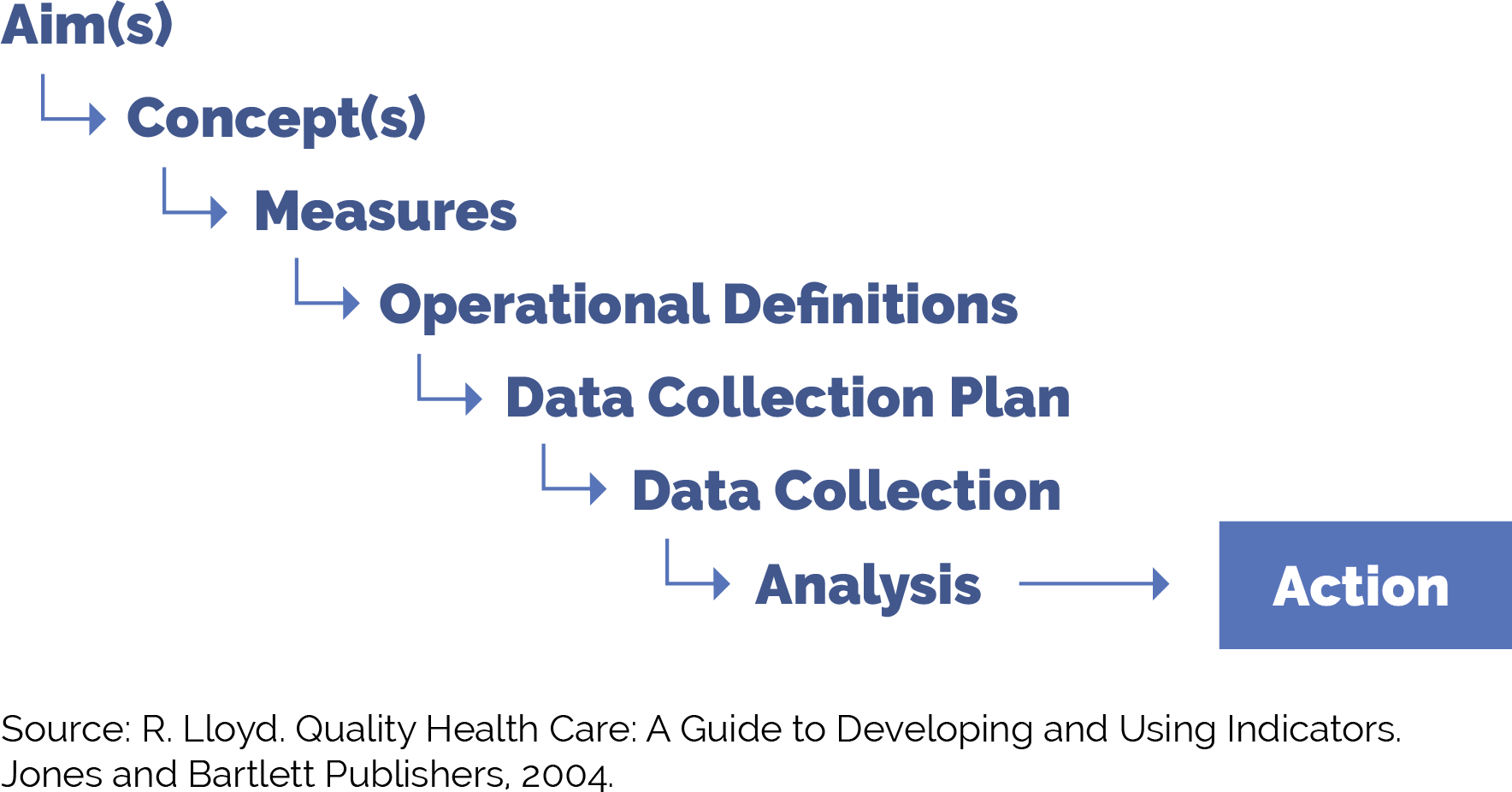

5. Develop a simple yet robust measurement strategy and learning system to guide your improvement efforts.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: implementation team.

A learning system enables a group of people to come together to share and learn about a particular topic, to build knowledge, and to speed up improved outcomes. A measurement strategy and learning system:

- Contains a balanced set of measures looking at outcomes, processes and possibly unintended secondary effects (e.g., increased cycle time and impact on team well-being).

- Incorporates the patient perspective and the perspective of staff (front desk and others), care team members, providers and management.

- Allows the team to determine if the process or system has improved, stayed the same or gotten worse.

- Helps guide improvement efforts and informs practice operations. See Appendix A: Sample Idealized System Diagram: Weaving Measurement and Learning Into Practice Operations for a sample system diagram of how your measurement strategy can be used to support practice operations.

Your practice should track the core and supplemental measures for hypertension control, comprehensive diabetes management and preventive ambulatory care visits. These can be considered outcome measures because there is ample evidence that improved care and management of chronic diseases will improve overall population health outcomes for effective chronic disease management.

In addition to the core and supplemental measures, practices should track process measures and balancing measures. Appendix C: Developing a Robust Measurement Strategy describes and defines the key milestones in the development of a robust measurement strategy, including definitions for each of these terms.

Suggested process measures:

- The percentage of patients 18 to 75 years of age with diabetes (type 1 and type 2) who receive a hemoglobin A1c test during the measurement year (NQF 0057).

- Percentage of patients ages 18 or older who are screened for high blood pressure and, if elevated or hypertensive, have a follow-up plan documented (CMS22v12).

- Percentage of adults who respond to a reminder to get scheduled for their visit.

- Percentage of adults who are due for a preventive/ambulatory visit that the practice reaches out to in order to schedule them if they are not already scheduled.

Suggested balancing measures: - One or more measures related to patient satisfaction.

- One or more measures related to staff satisfaction.

Practices can also look at other metrics to understand the progress of specific improvement initiatives over time. This may include:

- Progress on the Population Health Management Capabilities Assessment Tool (PhmCAT).

- Progress towards foundational competencies listed in this implementation guide. For example: “Yes or no: Did your practice achieve the foundational competency “Screen for Chronic Conditions?”

- Any other care gaps, clinical guidelines or measures your practice feels are important to prioritize.

Applying an equity lens

Your practice is likely achieving better outcomes with some patients than others. To understand these inequities, your practice should stratify your data based on race, ethnicity and language (REAL); sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI); and other patient characteristics (e.g., social needs, etc.). See more in Key Activity 4: Use a Systematic Approach to Decrease Inequities within the Population of Focus. The ability to segment data in such a manner can lead to profound insights about structural challenges that drive some of the health outcomes. The Advancing Equity Through Data Quality and Reporting section of the PHMI Data Quality and Reporting Guide provides more guidance on this.

Putting it all together

We recommend that your practice record your measurement strategy in one place. This Measurement Strategy Tracker contains all the fields we believe are most useful; it can be customized to meet your practice’s needs.

6. Plan and hold regularly scheduled meetings of the implementation team.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: team lead or clinical coordinator or other individual tasked with coordinating the work of the team.

- Hold time on team members' calendars for standing meetings. Consider biweekly (twice monthly) meetings to start with. The frequency, duration and focus of these meetings may change as you consider additional populations or subpopulations and additional sites or locations, and as the nature of the work changes.

- Having a clinical perspective is an important aspect of this work. Consider models that minimize overall impact to patients’ ability to access care (i.e., having meetings before working hours or during lunch times; having providers attend crucial, rather than all, meetings; scheduling during providers’ administrative time).

- Develop a system to efficiently report on all workstreams and track follow-up items. The Action Plan Template is one tool that can be used to focus your team around the foundational competencies and define responsibility for actions steps to be taken for each project your team has prioritized to work on.

7. Make adjustments based on data from the team’s measurement strategy and feedback loops.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: multidisciplinary team.

- Review data and feedback at least monthly and adapt efforts as needed. Adaptation could include any or all of the following:

- Amending the scope of work.

- Modifying meetings or meeting structures.

- Changing the team composition (adding or removing members).

- Refining activities to better meet the needs of patients and staff, improve outcomes, or reduce inequities.

- Modifying the measurement strategy and/or feedback loops to better understand what is (and is not) happening.

- On an annual basis, the team’s charter and core membership should be reviewed. As the goals of the implementation team are met, the team could disband, meet less frequently (e.g., twice per year) or fold this meeting into a similar standing meeting that occurs separately.

Resources

Health Center Quality Measurement Systems Toolkit

The Health Alliance of Northern California created a summary crosswalk of measurement sets that provides an overview of alignment between measurement systems. It includes in-depth information on each Uniform Data System (UDS) or Quality Incentive Pool (QIP) clinical measure for diabetes care and hypertension, which is contained in a spreadsheet.

The document also shares suggested clinical interventions and community interventions for controlling diabetes and high blood pressure in rural northern California.

Evidence base for this activity

Pandhi N, Kraft S, Berkson S, Davis S, Kamnetz S, Koslov S, Trowbridge E, Caplan W. Developing primary care teams prepared to improve quality: a mixed-methods evaluation and lessons learned from implementing a microsystems approach. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018 Nov 9;18(1):847. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3650-4. PMID: 30413205; PMCID: PMC6230270.

KEY ACTIVITY #2:

Update or Implement Clinical Practice Guidelines

This key activity involves all seven elements of person-centered population-based care: operationalize clinical guidelines; pre-visit planning and care gap reduction; behavioral health integration.

Overview

Clinical practice guidelines are established standards of care that provide evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis, treatment and management of various health conditions. They are established through a systematic review of evidence-based practice from a variety of sources, often from experts in the field. By following these guidelines, healthcare clinicians can ensure that patients receive high-quality care that is supported by current evidence-based practice. Clinical practice guidelines also help standardize care across different healthcare settings, which can improve patient outcomes, reduce healthcare costs and improve health equity.[4] Having guidelines is especially important for hypertension and diabetes management due to the complexity of ongoing management of these conditions.

Clinical practice guideline implementation is important because:

- They ensure that there are minimum standards of care within the practice.

- Care inequities can be reduced by providing universal standards.

- Guidelines allow for the development of other standard processes (i.e., standing orders), which help to reduce clinician burden. See Key Activity 9: Develop and Implement Standing Orders for more information.

- They facilitate a team-based model of care, which can be streamlined with standardized practices.

Clinical practice guidelines help promote equity by providing evidence-based recommendations for effective management of diabetes and hypertension. This ensures that care is standardized across the practice. While implementing clinical practice guidelines does not directly address social needs, enabling supportive care team members other than the primary care clinician to initiate care provides the opportunity to assess and to meet patients’ social needs.

Relevant HIT capabilities to support this activity include care guidelines, registries, clinical decision support, care dashboards and reports, quality reports, outreach and engagement, and care management/care coordination (see Appendix E: Guidance on Technological Interventions). Reports should have the capacity to filter by clinician, location and care team (where applicable).

Access to outside data may be a consideration or requirement (e.g., California Immunization Registry/immunization registry data and data from other practices) as services received outside the health center may be an important part of screening and follow-up. Ideally, this is accomplished by real-time data exchange, but where not possible, it may require manual entry. This may need to include not only the EHR but care coordination/population health management applications or freestanding referral registries. While claims data may be helpful in this regard, lag time may impact its usefulness. Patient-facing applications should be strongly considered to promote patient activation by helping ensure that patients are informed and appreciative of the nature and importance of recommended care. See Key Activity 24: Develop System to Provide Remote Monitoring for additional information.

Action steps and roles

1. Review the current, most up-to-date clinical guidelines and update appropriately.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: medical director (or equivalent) and quality improvement lead.

See the section titled Clinical Practice Guidelines earlier in this guide. Ensure your practice is using the latest guidelines.

In addition to those guidelines, you can review the following resources:

- ADA diabetes care recommendations (2023 standards).

- 2017 American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)/American Academy of Physician Assistants/Association of Black Cardiologists/American College of Preventive Medicine/American Geriatrics Society/American Pharmacists Association/American Society of Hypertension/American Society for Preventive Cardiology/National Medical Association/Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults.

PHMI Clinical Practice Guidelines.

- Kaiser Permanente Adult Blood Pressure Clinical Practice Guidelines.

- Kaiser Permanente Type 2 Diabetes Screening and Treatment Guideline.

2. Develop standard methods of updating clinic staff on changes within key guidelines.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: medical director (or equivalent) and quality improvement lead.

These updates could be provided during a set meeting time, via email communication, via video update, etc.

3. Ensure access to evidence-based clinical decision support systems.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: administration and medical director (or equivalent).

Clinical decision support provides staff with information that is relevant to the care situation at appropriate times to enhance health and healthcare.[5] This provides easy access to support such as clinical practice guidelines and medication alerts. These are sometimes integrated into the Electronic Health Record (EHR).

4. Regularly evaluate and support the infrastructure of patient care teams to ensure adequate redundancy and staffing.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: administration, medical director (or equivalent) and nursing director (or equivalent).

Part of developing the infrastructure for care teams to properly integrate clinical guidelines is providing adequate equipment for staff. This includes providing validated, automated monitors and adequate supplies of all blood pressure cuff sizes to each care team. Point-of-care A1c tests are another aspect of infrastructure that can be considered. Staff should also be trained upon hire, and annually thereafter, on proper blood pressure measurement procedures. This ensures that all staff are trained and available to utilize equipment. Staff should also be trained on other aspects of workflows, such as rooming, pre-visit planning (PVP), huddles, etc., in order to ensure that care does not suffer if a crucial staff member is unavailable on a certain day.

Additionally, practices should regularly evaluate clinic workflows and clinician panels to ensure that the number of staff that are allocated to each area is adequate. See the PHMI Empanelment Guide and Care Teams & Workforce Guide for more information.

5. Develop guidelines that reflect a spectrum of treatment needs.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: administration, medical director (or equivalent) and nursing director (or equivalent).

Guidelines should provide evidence-based recommendations for intensification of treatment, which emphasizes performance feedback. This can be for initiatives such as following up on lab results or utilizing guidelines for medication measures. Additionally, clinicians should be educated regarding how to best address common side effects and lab abnormalities.

Implementation tips

Facilitate opportunities to share/collaborate with behavioral health colleagues about the clinical practice guidelines for chronic diseases management. Much of chronic disease management requires patients to engage in behavior change. Behavioral health colleagues bring skills and strategies that best support patients in making and sustaining the changes necessary to initiate and maintain behavior change

Resources

KEY ACTIVITY #3:

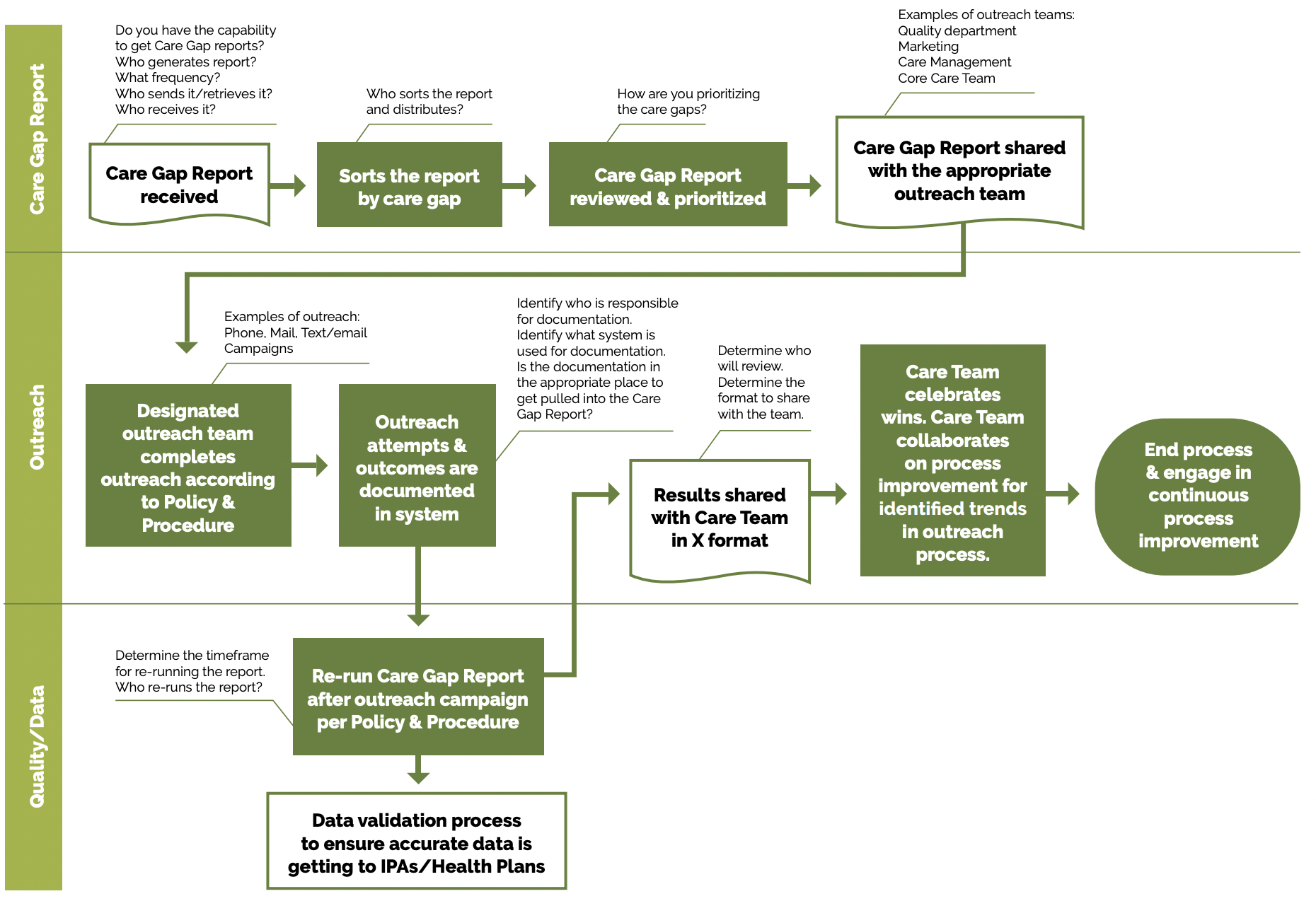

Use Care Gap Reports or Registries to Identify All Patients Eligible and Due for Care

This key activity involves all seven elements of person-centered population-based care: ooperationalize clinical guidelines; implement condition-specific registries; address social needs.

Overview

This foundational activity provides detailed guidance on how to reliably and efficiently develop and use a regularly updated list of patients eligible for recommended or standard screenings or interventions (e.g., blood pressure, lab work, etc.) through a care gap report or registry. Please note that this activity focuses on diabetes and hypertension; many other preventive and maintenance services are needed to provide comprehensive preventive care (see the Pre-Visit Planning: Leveraging the Team to Identify and Address Gaps in Care resource for a more complete list).

Care gaps are gaps between the recommended care that a patient should receive according to clinical guidelines and the care a patient actually receives.

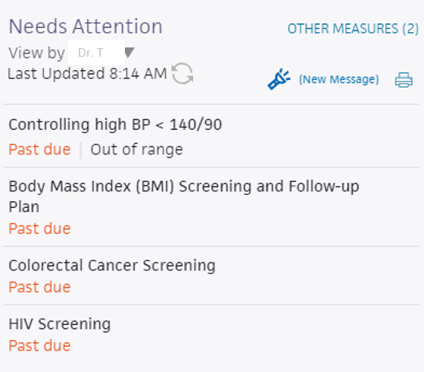

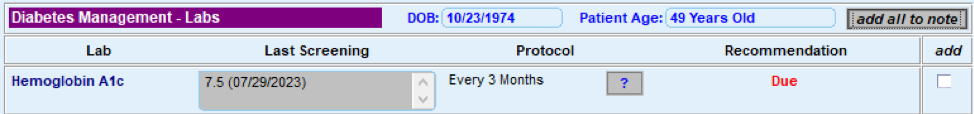

Most EHRs already have a module that identifies what services are due for each patient (see examples below).

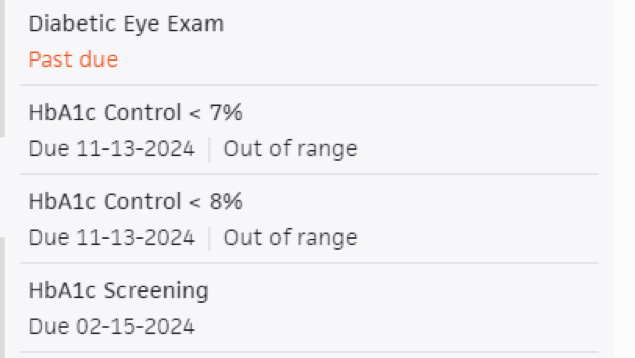

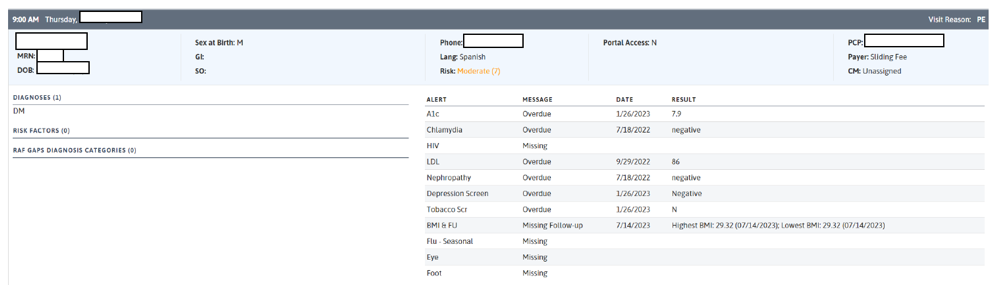

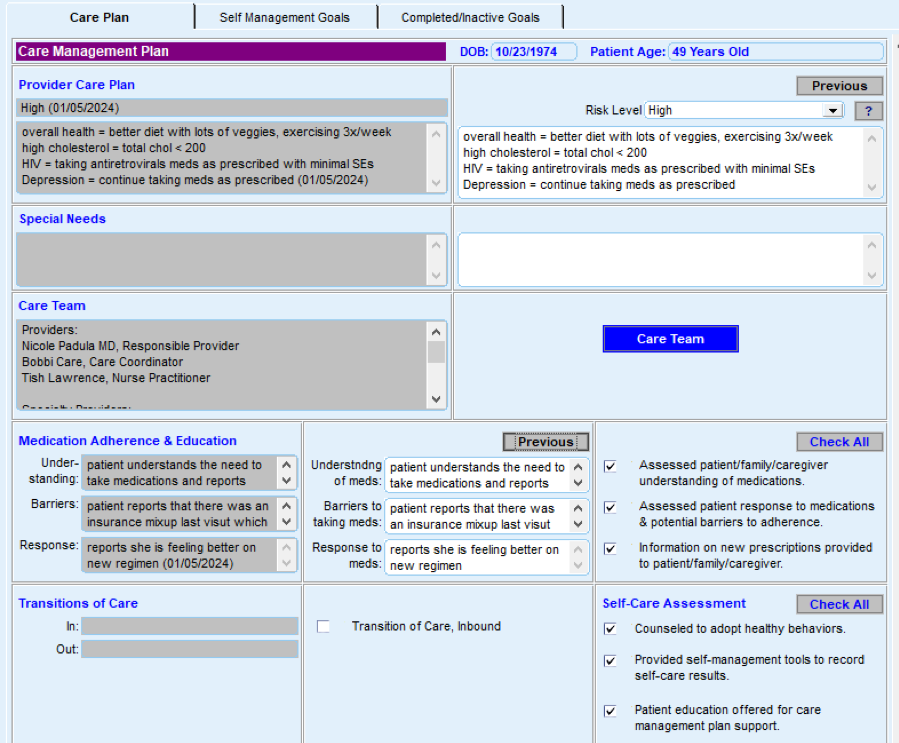

FIGURE 4: EXAMPLE OF A CARE GAP REPORT FOR AN INDIVIDUAL PATIENT (BLOOD PRESSURE)

FIGURE 5: EXAMPLE OF A CARE GAP REPORT FOR AN INDIVIDUAL PATIENT (HEMOGLOBIN A1C)

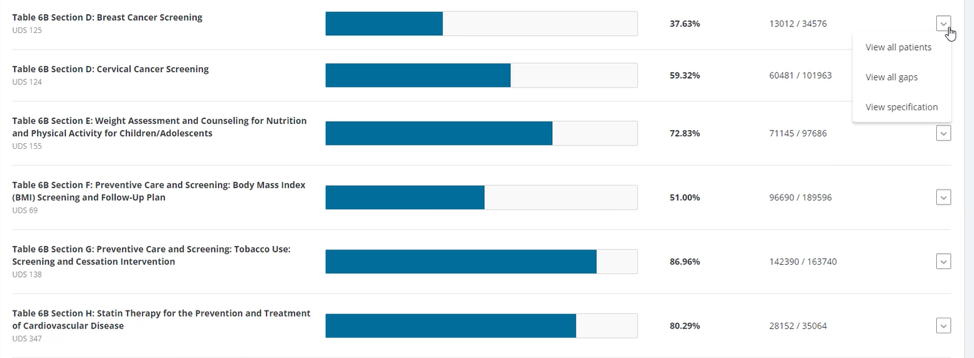

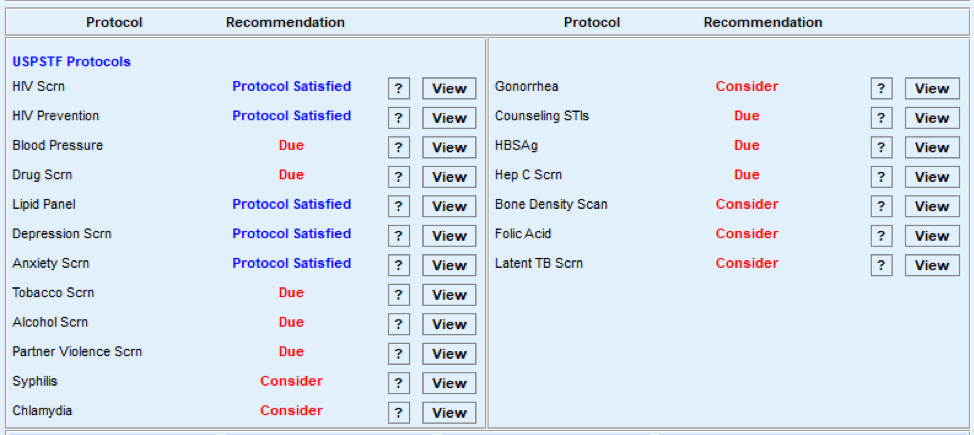

FIGURE 6: EXAMPLE OF A CARE GAP REPORT SUMMARY AT A POPULATION LEVEL

A registry is a list of patients with a specific characteristic that can be used for tracking aspects of screening, treatment or outcomes. At minimum, a registry should include:

- Medical record number. (MRN)

- Patient name.

- Date of birth.

- Contact information.

- Race, ethnicity, and preferred Language (REAL).

- SOGI data.

- Clinical data points that are being checked for care gaps.

An example chronic care registry report from the American Medical Association highlights clinical data points that may be important to consider when building a chronic care registry.

Care gap reports are reports embedded in EHRs that use the registry concept to identify patients assigned to your care team or in some other cohort, who have a specified care gap.

Rather than put the responsibility on an individual care team member for searching through charts or remembering which patients need further preventive care or follow-up, this key activity provides guidance on how the practice can efficiently leverage EHRs to identify patient care gaps.

Care gap reports are essential for practices to understand and continually improve consistency and reliability for meeting guidelines for preventive care and chronic disease management. At the care team level, care gap reports focus on gaps for patients assigned to your care team and help your team understand which patients you are responsible for. They can be used to:

- Support improvements to the pre-visit planning (PVP) process, standing orders and other routine clinical workflows designed to systematically identify and address gaps in recommended care.

- Prioritize patients to whom care teams should provide proactive outreach and reminders for engaging in care.

- Support quality improvement efforts with an equity lens.

- Improve your performance on key measures by ensuring you are able to do follow-up assessments/screenings for patients overdue for services (such as labs, ophthalmology checks for people with diabetes, foot screening for neuropathy, etc.).

Actively identifying and acting on care gaps ensures all eligible patients assigned to your practice receive timely screenings for chronic disease and other preventive services. This reduces the burden on the healthcare system by preventing more severe health issues in the future. Furthermore, this reduces missed or delayed diagnoses. For adults with chronic conditions, care gap reports can identify patients who are due for regular or infrequent required screenings in accordance with clinical care guidelines, including guidelines that may be established by specific payors. They also can identify opportunities for screening and improvement for controlling said chronic conditions.

Many practice patients experience barriers to accessing care due to structural and historical racism, homophobia, xenophobia and other biases that have historically disadvantaged individuals and groups from receiving equitable services. Defining clear criteria and gaps for patients due for specific screenings or preventive services helps to illuminate groups that have not had equitable access. It also combats biases by standardizing expectations for who is due for what care, providing a starting point for ensuring reliable and equitable access.

Staff can identify potential barriers and challenges for patients accessing and engaging in care by using enhanced care gap reports to filter and display the data alongside demographic information, social needs, behavioral health needs and communication preferences. This information can be used to promote a person-centered approach when designing the care plan, promoting self-care and conducting other patient engagement activities, such as conducting outreach in the patients’ preferred language.

Furthermore, care gap reports that segment the data into cohorts based on demographic and other personal information may help the team identify inequities in care, access and outcomes, which can inform improvement efforts. For example, therapeutic intensity requirements may differ by population. It is also important to gain input from the patient to ensure that their needs are being met.

Care gap reports can be used during pre-visit planning (PVP) to identify people for whom social needs screening has not yet been completed. This creates an opportunity to identify unmet social health needs and to connect patients with resources that address their social needs. See Key Activity 10: Develop or Refine and Implement a Pre-Visit Planning Process for more information.

Many EHRs already have a module that identifies what services are due for each patient whereas others do not. Where this functionality is available, it may not be configurable to align with the health center’s specific protocol or be able to incorporate outside data. Other options for developing registries include supplemental applications, population health platforms and freestanding customized databases that draw data from the EHR and other sources.

Care gap reports may be embedded in EHRs or made available through other technology channels (See Appendix E: Guidance on Technological Interventions.)

They are useful both at the individual patient level and aggregated to identify groups of patients to facilitate population-level management through registries.

A registry can be thought of as simply a list of patients sharing specific characteristics that can be used for tracking and management. Both care gap reports and registries should have the capacity to segment patients by age, gender, race/ethnicity and language.

Other relevant HIT capabilities to support/relate to this activity include care guidelines, care dashboards and reports, quality reports, outreach and engagement, and care management/care coordination.

(See Appendix E: Guidance on Technological Interventions.)

Access to outside data (e.g., California Immunization Registry/immunization data and data from other practices) may be a consideration or requirement as services received outside the practice may be part of compliance. While claims data may be helpful in this regard, lag time may impact its usefulness. Patient-facing applications should be strongly considered to ensure patients are informed and appreciative of the nature and importance of recommended care. In California, many healthcare organizations are required or have chosen to participate in the California Data Exchange Framework (DxF), which can facilitate data sharing between clinics, managed care plans (MCPs) and other partners.

Action steps and roles

1. Plan the care gap report.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: panel manager or data analyst. If it is not clear how the report can be produced, this step may involve one or more people from the practice who work on the EHR and possibly the EHR vendor.

As a team, decide what screenings or treatment guidelines are appropriate for your population of focus and prioritize the most important care gaps to run reports on. Start with the core and supplemental measures and any process measures your practice is tracking, then consider if there are any other gaps, clinical guidelines or measures your practice feels important to prioritize.

Identify the inclusion criteria for each report, such as age, any exclusion criteria and factors that make someone high risk.

Care gap reports should at minimum include monitoring for control of the following:

Among persons 18 to 75 years old with diabetes:

- No hemoglobin A1c test within the past six months.

- A1c >9% without a follow-up.

- Missing a urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio test in the past 12 months.

- Missing diabetic eye exam in the past 12 months.

- Missing diabetic foot exam in the past 12 months.

Among persons 18 to 85 years old with hypertension:

- No documentation of blood pressure in the past 12 months (or ever).

- If the last blood pressure was uncontrolled.

- If there was no documented follow-up if the blood pressure was elevated.

Care gap reports should also be developed to flag persons not meeting HEDIS measure thresholds who require follow-up because of positive screening results or lab values outside recommended limits. Many such reports may already be part of your clinic’s EHR.

2. Build the report.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: data analyst.

Determine whether the EHR has an existing report or one that can be modified to fit the inclusion criteria. You should talk to staff who are familiar with the electronic record; in some cases, it may be necessary to consult with the EHR vendor to confirm this information and how to run the report.

The care gap format should include:

- Criteria for inclusion in the report.

- The overall compliance rate for the care gap being measured.

- All patients eligible for the screening or intervention and their addresses and phone numbers.

- The last date the test was performed, if known or if applicable; the previous results; and the type of test used.

- Preferred method of communication (e.g., phone, email, text).

Reports should be able to display and/or disaggregate the data based on:

- Race, ethnicity, and language (REAL) as well as sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI).

- Any known social or behavioral needs.

- Communication preferences or other preferences that would inform the screening modalities offered or treatment preferences, such as documented declination of prior screenings or medications.

- Data on any other characteristic, including insurance data, that could pose a barrier to completing screening or influence treatment choices.

Report developers should also work to allow for evaluation of data on a clinician panel, clinic unit, whole clinic and health system level.

3. Standardize the data format.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: panel manager or data analyst.

Standardizing the data format and where it is entered is critical to ensuring accuracy in the resultant report. Once you know that a report can be produced, understand the specific data elements that are needed to produce the reports.

Document how each data element must be entered into the EHR in order to populate the fields needed for reporting. In some cases, data on completion of screening must be entered by hand (e.g., when the test is performed by a lab that does not communicate with the legacy EHR). Doing this will require a decision on the part of the practice as a whole and may require staff training and reinforcement on an ongoing basis. Where issues or apparent confusion is identified, regular discussion at team huddles or staff meetings will help in maintaining a standard approach.

Tip: Assign responsibility for the initial review of the reports to confirm data integrity.

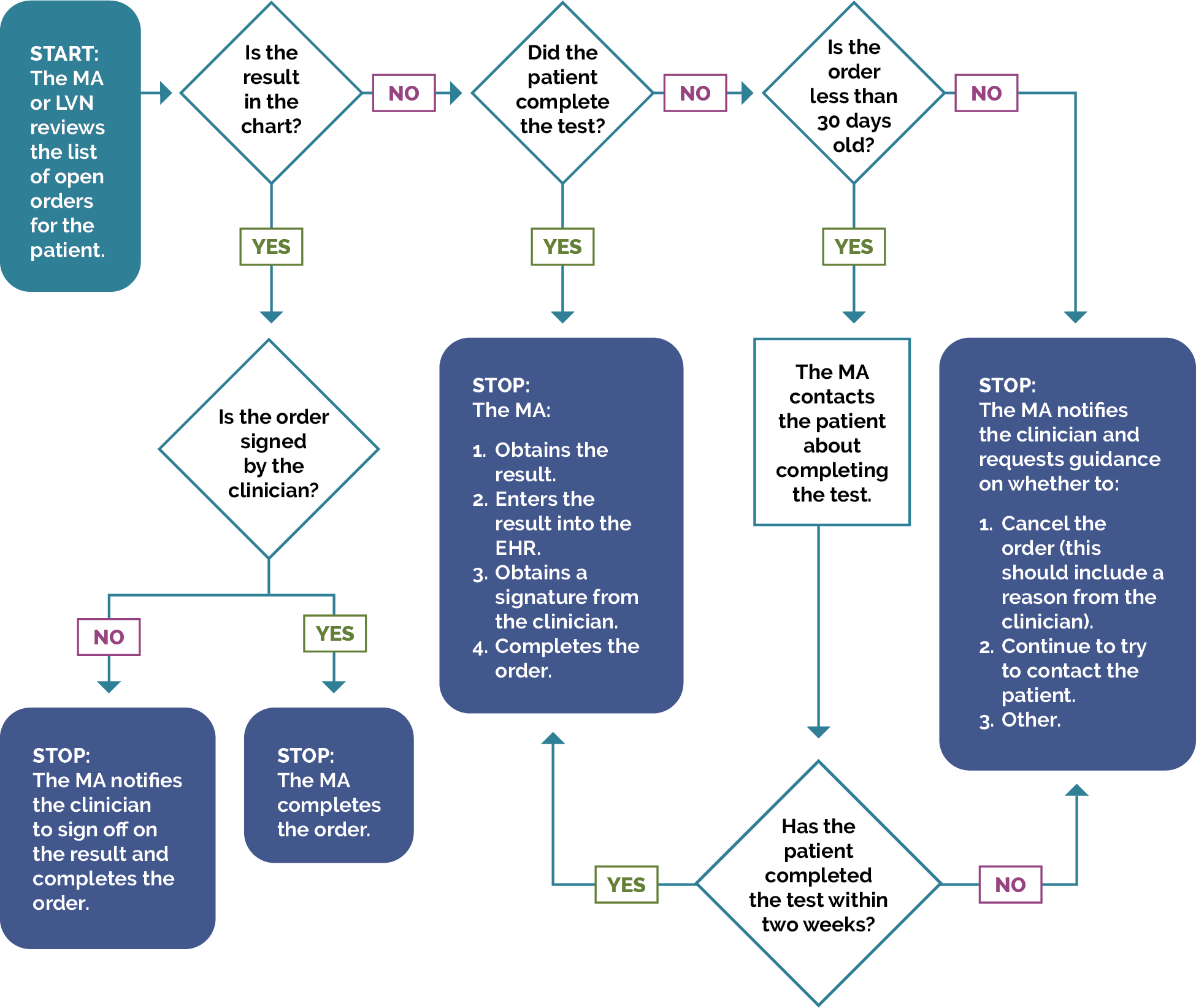

4. Develop workflows to improve patient screening and preventive care completion rates.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: panel manager, care team and EHR specialist (or equivalent).

At the patient level, ensure that the care gap report can be used for or linked with reminders or alerts for clinicians, as well as for reminders to patients who need to come in to the clinic for screening or follow-up. As an example, a care gap report could alert the care team that a diabetic patient is in need of a foot check in accordance with the guidelines. For example, a standing order could trigger the MA who is trained in foot screening to do the foot check at the time of rooming. The workflow in Figure 7 applies to both chronic and preventive screening.

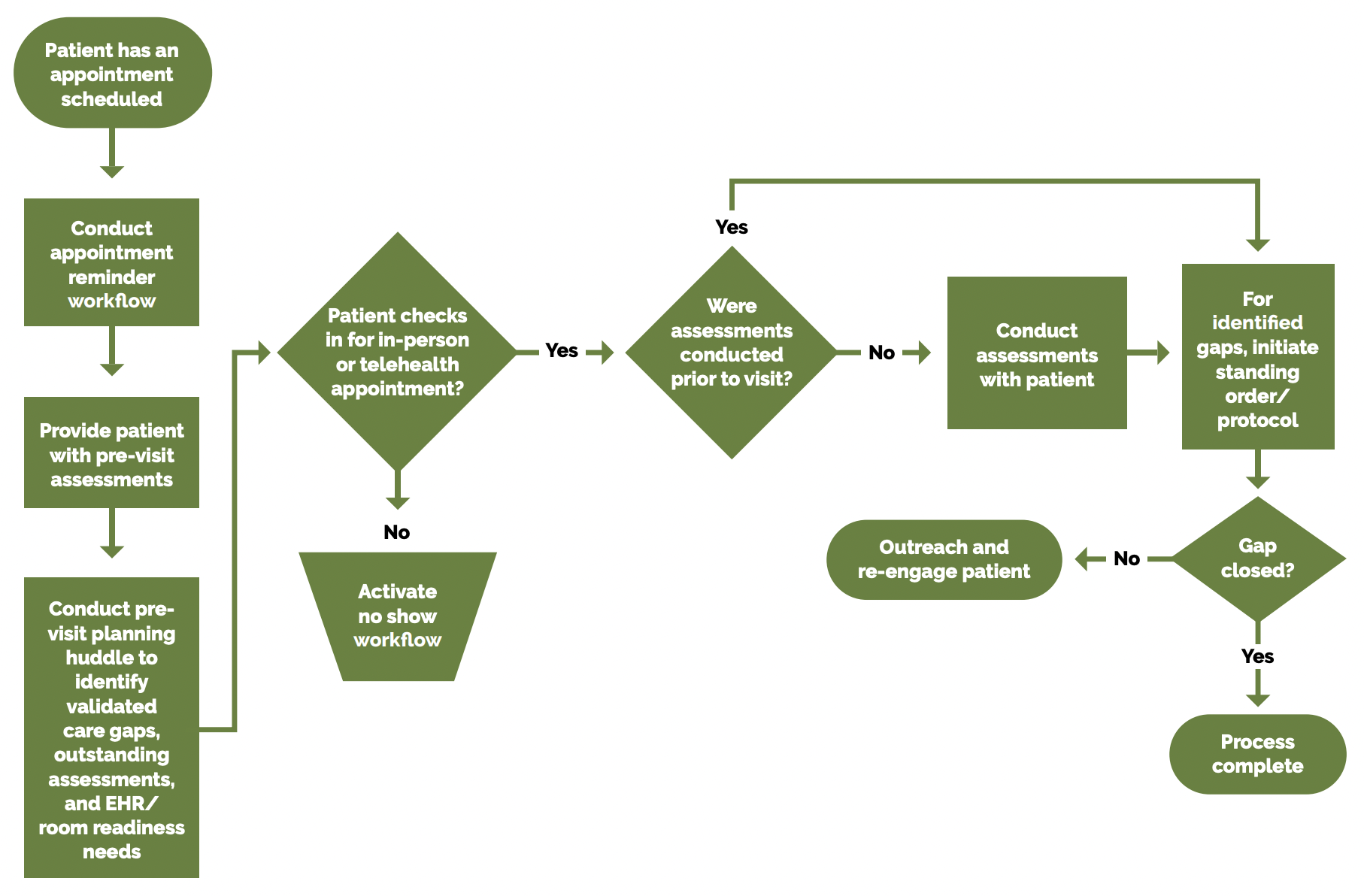

FIGURE 7: SCHEDULED PREVENTIVE CARE VISIT WORKFLOW

See the PHMI Care Teams and Workforce Guide Resource 6: Workflow Examples for more information.

Depending on communication preferences that have been expressed by patients, the patient care gap report may be exported to an automated reminder system that can trigger reminders by phone, text, email or postal mail.

In addition, as part of the practices’ PVP process, patient care gaps should be reviewed and flagged as part of the daily huddle. See Key Activity 10: Develop or Refine a Pre-Visit Planning Process for more details.

An example of this is the Axis Community Health project implemented through participation in the Population Health Learning Network. Axis Community Health wanted to improve its behavioral health data infrastructure to better track patient outcomes, adjust treatment and provide quality care. This case study describes the registry they created, key changes and outcomes.

5. Develop a process for reviewing gaps at the population level.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: panel manager.

Set a report frequency to review care gap reports at regular care team meetings or huddles in order to develop a plan for improvement at the population level. This may include an outreach campaign to build community awareness of the value of screenings and the availability of easily accessed screening services. Reports should be able to be drilled down to the clinician level for accountability and used by the care team to improve performance.

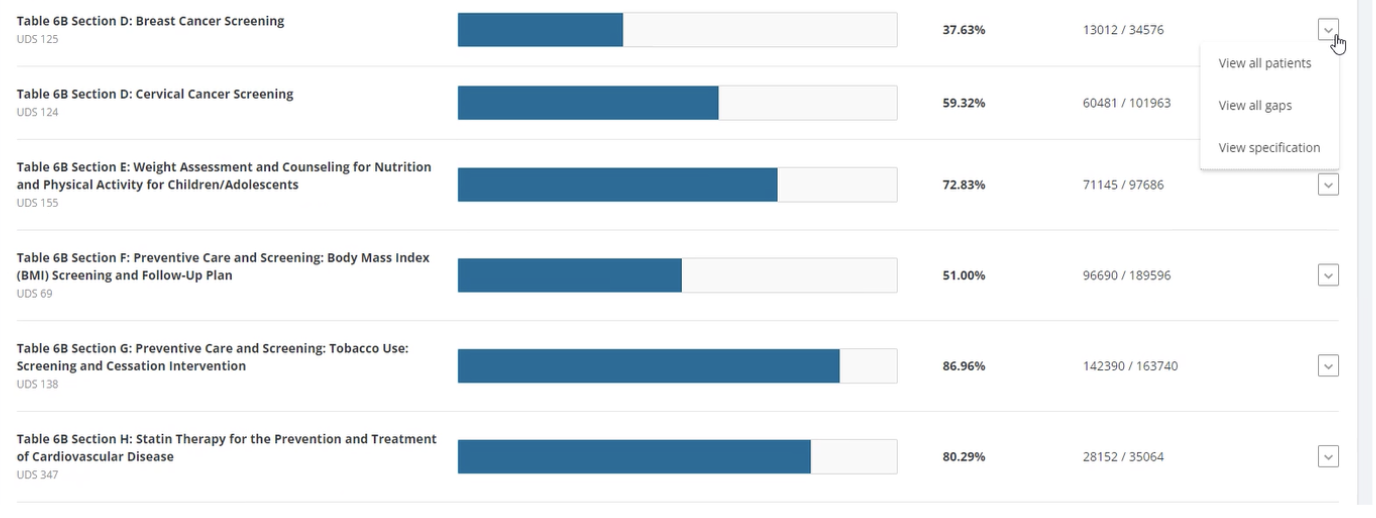

FIGURE 8: EXAMPLE OF A POPULATION CARE GAP REPORT DASHBOARD

Implementation tips

- Consider using other practice staff to help close gaps in care. For example, front office staff can assist with scheduling a follow-up nonacute visit to address gaps in care if a patient comes in for a sick visit.

- Consider incorporating chronic disease management into sick visits to further expand patients’ opportunity to receive care.

- Treatment intensity required for a patient can be benchmarked between providers in a practice. This can be accomplished by comparing treatment intensity rates over a period of time (i.e., three months), which can then be compared to the clinical effectiveness of interventions (i.e., diabetes control or hypertension control).

Resources

Evidence base for this activity

Conderino S, Bendik S, Richards TB, Pulgarin C, Chan PY, Townsend J, et al. The use of electronic health records to inform cancer surveillance efforts: a scoping review and test of indicators for public health surveillance of cancer prevention and control. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2022 Apr 6;22(1).Sequist TD, Zaslavsky AM, Marshall R, Fletcher RH, Ayanian JZ. Patient and Physician Reminders to Promote Colorectal Cancer Screening. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009 Feb 23;169(4):364.

KEY ACTIVITY #4:

Use a Systematic Approach to Decrease Inequities Within the Population of Focus

This key activity involves all seven elements of person-centered population-based care: operationalize clinical guidelines; implement condition-specific registries; proactive patient outreach and engagement; pre-visit planning and care gap reduction; care coordination; behavioral health integration; address social needs.

Overview

This activity provides guidance for a systematic evidence-based approach for identifying and then reducing inequities for children. It focuses on the first primary driver in PHMI’s equity approach: Reduce inequities for populations of focus.

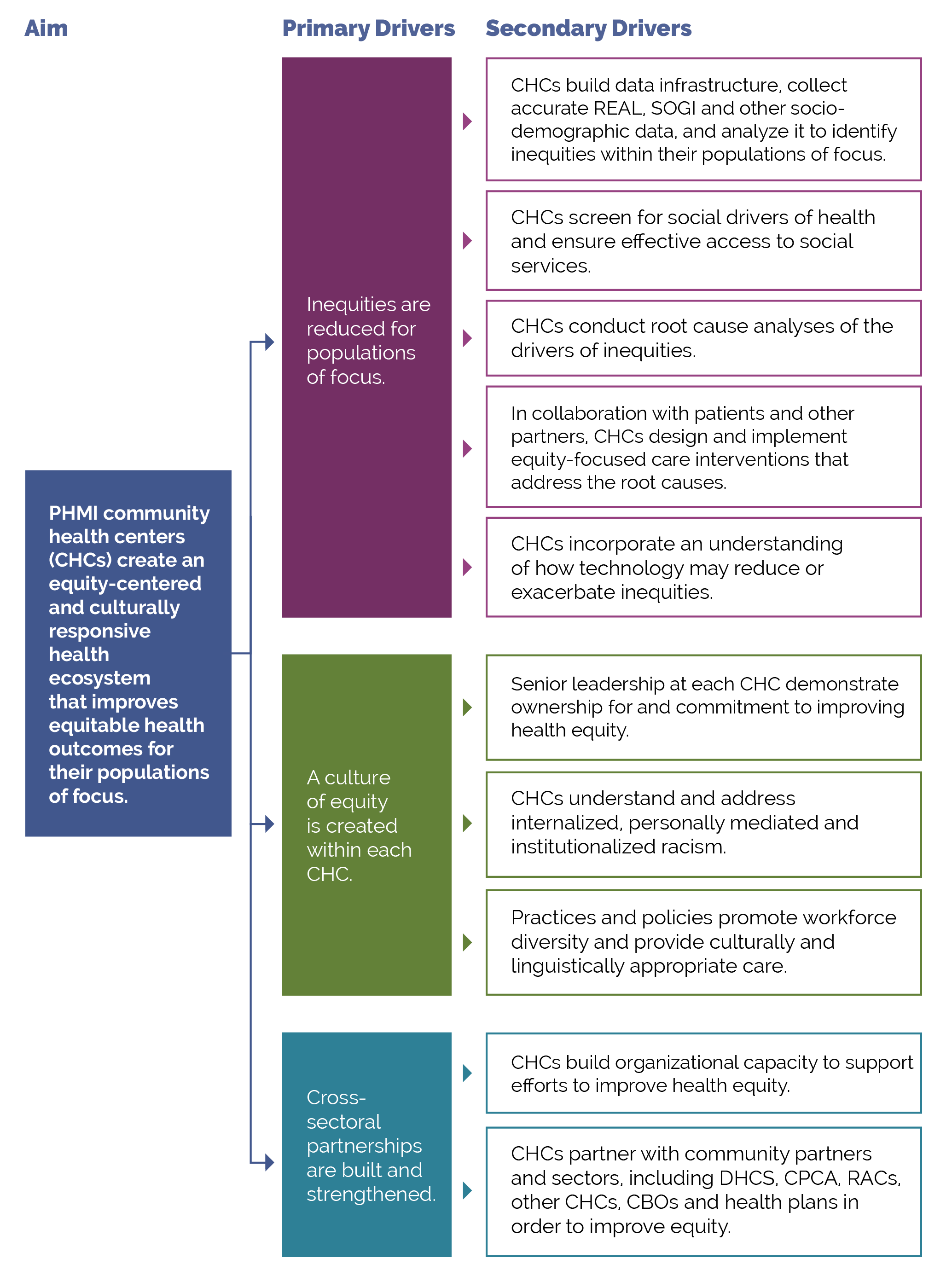

FIGURE 9: PHMI EQUITY DRIVER DIAGRAM

Your practice is likely achieving better outcomes with certain populations or subpopulations and worse outcomes with others. Inequitable outcomes are often the result of social and cultural factors that serve as barriers to accessing care. They are generally most acute among persons of color, immigrants, persons speaking a primary language other than English and other populations who have been marginalized. As we work to reduce and, over time, eliminate inequitable health outcomes, we need to understand both what contributes to these different outcomes as well as factors that do not contribute to them

This includes recognizing that race is a social construct determined by society’s perception. While some conditions are more common among people of certain heritage, inequities in conditions such as cancer, diabetes and adverse maternal outcomes have no genetic basis. While genetics do not play a role in these inequitable outcomes, the extent to which inequities in the quality of care received by people of color contribute to inequitable health outcomes has been extensively documented.[6] These inequities are often a direct result of racism, particularly institutionalized racism – that is, the differential access to the goods, services and opportunities of a society by race.[7] Racial health inequities are evidence that the social categories of race and ethnicity have biological consequences due to the impact of racism and social inequality on people’s health.[8] It is also critical to recognize that we have policies, systems and procedures that unintentionally cause inequitable outcomes for racial, ethnic, language and other minorities, in spite of our genuine intentions to provide equitable care and produce equitable health outcomes.

Improving your practice’s key outcomes for each population of focus requires a systematic approach to identifying equity gaps (e.g., who your practice is not yet achieving equitable outcomes for) and then using quality improvement (QI), collaborative design, systems thinking and related methods to reduce these equity gaps.

Identifying and meeting patients’ social needs are key drivers of reducing inequitable health outcomes. We provide additional guidance in this key activity on how to both reduce inequities and meet patients’ social health needs.

Access to the data required to identify and monitor inequities, as outlined in the key actions below, is fundamental to this activity.

Relevant HIT capabilities to support this activity include care guidelines, registries, clinical decision support (modifications required to consider disparate groups), care dashboards and reports, quality reports, outreach and engagement, and care management/care coordination (see Appendix E: Guidance on Technological Interventions).

EHRs have the ability to capture basic underlying socioeconomic, sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) and social needs-related data but may in some cases lack granularity or nuances that may be important for subpopulations. Mismatches between how the UDS captures REAL data versus how EHRs capture or MCPs report data can also create challenges. This may require using workarounds to capture these details. It is also important to ensure that other applications in use that may have separate patient registration processes are aligned. Furthermore, tracking inequities in accessing services not provided by the health center may also require attention to data sources or applications outside the EHR.

Health centers should also be alert to the potential for technology as a contributor to inequities. For example, patient access to telehealth services from your practice may be limited by the inequitable distribution of broadband networks and patient financial resources (e.g., for phones, tablets and cellular data plans). The Techquity framework can be a useful way to structure an approach to ensure that technology promotes rather than exacerbates inequity.

Language, literacy levels, technology access and technology literacy should also be considered and assessed against the populations served at the health center.

Action steps and roles

1. Build the data infrastructure needed to accurately collect REAL, SOGI, social needs and other demographic data.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: data analyst.

- Race, ethnicity and language (REAL)

- Sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI)

The PHMI Data Quality and Reporting Guide provides guidance and several resources for collecting this information. According to this guide, the initial step in addressing inequities is to collect high-quality data that fosters a holistic view of patient characteristics and needs. This entails incorporating REAL data, demographic data (age, SOGI, geography) and social needs data. By collecting and monitoring this information, healthcare practices can gain valuable insights into inequities in access, continuity and health outcomes. Steps 2 to 4 below provide more information on this process.

Collecting REAL information allows practices to identify and measure inequities in care while also ensuring that practices are able to interact successfully with patients. This is done by understanding patients’ unique culture and language preferences.[9] KHAQuality.com has a toolbox that assists with REAL data collection.

The Uniform Data System Health Center Data Reporting Guidance (2023 Manual) provides detailed guidance on REAL and SOGI. Note: While UDS does not currently require that practices report on the specific primary language of each patient, practices should make an effort to identify and record each patient’s primary preferred language since UDS reporting still requires languages other than English to be reported.

Accurate data collection requires appropriate fields and options in the EHR and other employed technologies, as well as appropriate human workflows in collecting the data. Staff responsible for data collection should be continuously trained and assessed for best practices in data collection, including promotion of patient self-report.

In addition, practices should work to ensure that patients understand the importance and use of this information to help them feel comfortable with supporting its collection. High rates of “undetermined” or “declined” responses in these fields may be indicative of the need to train staff in how to ask these questions and to communicate the importance of the information and how it will be used to improve the healthcare the patient receives. An example of how this was incorporated into a practice was Lyon-Martin Community Health Services partnering with its EHR provider in order to build trust with disclosing this type of data.

Collecting this data is important, especially to obtain a complete picture of health for patients who identify as transgender. There are certain risks and condition indicators that are gender specific, which impact how clinicians provide care to a patient. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health has provided further guidance regarding standards of care related to gender diversity.

2. Use the practice’s EHR and/or population health management tool to understand inequitable health outcomes at your practice by stratifying your data.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: data analyst.

This includes reviewing your care gap report/care registry and being able to stratify all of the following:

- Core measures for the population of focus.

- Supplemental measures for the population of focus.

- Process measures for the population of focus.

Stratify this data by:

- REAL.

- SOGI.

- Other factors that can help identify subpopulations in need of focused intervention to reduce an equity gap (e.g., immigrants, people experiencing homelessness, etc.).

This is not a one-time event, but rather a continuous process (see step 13 below). It should be done in tandem with step 3 below.

Each practice should define the frequency of review and use of its registry to stratify data. In early use, the stratified data will support the identification of areas of inequity and allow for interventions to be prioritized.

3. Screen patients for social needs.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: care team.

Key Activity 17: Use Social Needs Screening to Inform Patient Treatment Plans provides guidance on screening patients for health-related social needs and how the information can begin to be used to inform patient treatment plans, including referral to community-based services. This is not a one-time event, but rather a continuous process. It should be done in tandem with step 2 above.

4. Analyze the stratified data from steps 2 and 3 to identify patterns in inequitable outcomes within the population of focus.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: data analyst, QI leads and care team.

Analyze the stratified data from steps two and three to identify patterns in inequitable outcomes.

This includes:

- Utilizing tools to examine, visualize and understand disparities across different populations or subpopulations.

- Data over time (using run charts).

- Exploring trends, patterns and significant differences to understand which demographic groups will require a focused effort to close equity gaps.

Update your practice’s measurement strategy so your practice’s improvement efforts remain centered around advancing equitable outcomes. Some examples include creating specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, time-bound, inclusive and equitable (SMARTIE) goals and updating your process and outcome measures so you can understand differences by REAL or SOGI indicators. See Appendix C: Developing a Robust Measurement Strategy for more.

This is not a one-time event but rather a continuous process (see step 13 below). Periodic review of stratified data allows for recognition of gap closures and emergence of new disparities.

5. Conduct a root cause analysis for each subpopulation that the practice does not yet have equitable outcomes for.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: multidisciplinary team.

Select root cause analysis approaches that work best for the equity gap you are closing include:

- Engagement with and gathering of information from patients affected by the health outcome in your root cause analysis (see step 6).

- Brainstorming.

- Systems thinking (understanding how interconnected social, economic, cultural and healthcare access factors may be impacting the health outcome).

- Tools that rank root causes by their impact and the feasibility of addressing them (e.g., a prioritization matrix and/or an impact effort matrix).

- Visual mapping of root causes and effects (e.g., fishbone diagram).

- Focused investigations into selected root causes to gather qualitative data through interviews, surveys or focus groups with the subpopulation of focus.

Present the findings to a broader group of stakeholders to validate the identified root causes and gain additional insights. Incorporate the stakeholders’ feedback and refine the analysis, as needed.

6. Partner with patients to develop insights that will help you develop successful strategies.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: care team and people with lived experience (patients who are members of the population[s] of focus).

Using one or more human-centered design methods, such as focus groups, 7 - Stories, Journey mapping, etc. (see links to these methods below), work with members of each population of focus to better understand:

- Their assets, needs and preferences.

- Cultural beliefs, including traditional healing practices.

- Beliefs and level of trust in healthcare generally and in the topic of focus specifically (e.g., cancer screening, immunizations, behavioral health, etc.).

- Barriers to accessing care.

- Barriers to remaining engaged in care.

- Trusted sources of information or communication mechanisms for this population.

- Their ideas for improving health outcomes.

The patients you partner with for this and other steps in this key activity may be part of a formal or informal patient group and/or identified and engaged specifically for this equity work.

7. Identify key activities that address or partially address the root causes of the identified equity gaps.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: care team and people with lived experience.

Based upon the insights your practice has developed for a population of focus and your root cause analysis, determine which of the key activities in this implementation guide could address or partially address the equity gap. This could also include making physical adjustments to the environment in order to make the practice more welcoming or culturally responsive.

Most of the key activities in this guide either explicitly address an equity challenge or can be adapted to better address an equity challenge. Examples of key activities that can be adapted to reduce identified equity gaps include (but are not limited to):

- Key Activity 20: Strengthen Community Partnerships.

- Key Activity 11: Screen for Chronic Conditions.

- Key Activity 8: Proactively Reach Out to Patients Due for Care.

- Key Activity 17: Use Social Needs Screening to Inform Patient Treatment Plans, such as providing a referral for one of the CalAIM Community Supports.

- Key Activity 18: Coordinate Care.

- Key Activity 22: Continue to Develop Referral Relationships and Pathways.

- Key Activity 23: Strengthen a Culture of Equity.

8. Develop new strategies/ideas to address the identified equity gaps.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: care team and people with lived experience.

If one or more of your root causes cannot be addressed fully through key activities in this guide, use one or more human-centered design methods (see resources below) to develop ideas to improve health outcomes and reduce inequities among people with chronic conditions.

Developing these ideas is best done with representatives who are diagnosed with a chronic condition (as they have expertise and experience that may be missing from the practice’s care team). Compensating these patients and community members for time spent on improvement activities is a best practice. During this brainstorm, you are developing ideas without immediate judgment of the ideas in an effort to generate dozens of potentially viable strategies.

Selected resources on human-centered design and collaborative design

- Center for Care Innovations (CCI) Human Centered Design Curriculum via CCI Academy.

- IDEO’s The Field Guide to Human-Centered Design.

- IDEO’s Design Kit: Methods.

9. Determine which strategies to test first.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: care team and people with lived experience.

Steps 7 and 8 above help your practice identify existing key activities and generate new ideas.

There are many ways to prioritize ideas. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement often recommends a priority matrix.

If you have organized your key activities and new ideas into themes or categories, you may choose to work on one category or select one to two ideas per category to work on.

The number of key activities and/or new ideas that you prioritize for testing first should be based on the team’s bandwidth to engage in testing. Therefore, it is critical to determine the bandwidth for the team(s) that will be doing the testing so that you can determine how many ideas to test first.

10. Use quality improvement (QI) methods to begin testing your prioritized key activities and new ideas.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: care team and people with lived experience.

Nearly all the key activities and all of your new ideas will require some degree of adaptation to use them within your practice and to be culturally relevant and appropriate to your patients.

Use plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles, generally starting as small as feasible (think in ones — e.g., one clinician, one hour, one patient, etc.) and becoming larger as your degree of confidence in the intervention grows.

Whenever testing a key activity or new idea, we recommend that the practice:

- Use PDSA cycles to test your ideas and bring them to scale. See more information on PDSAs below in the Appendix C: Developing A Robust Measurement Strategy.

- Generally, start with smaller-scale tests (e.g., test with one patient, for one afternoon, in a mailing to 10 patients, etc.). Use the chart titled How Big Should My Test Be? in the Implementation Tips section below to help you decide what test size is most appropriate.

Develop or refine your learning and measurement system for the ideas you are testing. A simple yet robust learning and measurement system will help you understand improvements, unintended secondary effects and how implementation is going.

By working out the inevitable challenges in the idea you are testing using a smaller-scale PDSA cycle, ultimately, the improvement activity will work better for patients and be less frustrating to the care team. Testing and refining also can eliminate inefficient workarounds that occur when a new process or approach is imposed onto an existing system or workflow.

Select resources on Quality Improvement (QI)

Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Quality Improvement Essentials Toolkit, which includes:

- Cause and effect diagrams.

- Driver diagrams.

- Failure modes and effects analysis.

- Flowcharts.

- Histograms.

- Pareto charts.

- PDSA worksheet.

- Project planning form.

- Run charts.

- Scatter diagram.

IHI’s Videos on the Model for Improvement (Part one and Part two).

11. Implement (bring to full scale and sustain) those practices that have proven effective.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: care team.

Once an idea has been well tested and shown to be effective on a small scale, it is time for your practice to “hardwire” the idea, approach or practice into your daily work. Consider using the MOCHA implementation planning worksheet to think through:

- Measurement.

- Ownership.

- Communication (including training).

- Hardwiring the practice.

- Assessment of workload.

Sometimes implementation may require that you update your protocol and/or policies and procedures for the populations of focus.

12. Once you have tested, refined and scaled up the initially prioritized ideas, begin testing other ideas.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: care team and people with lived experience.

This might include going back to ideas that were elicited previously but were not initially prioritized for implementation. You might also move through the testing steps above to generate and prioritize new ideas or adapt ideas to better serve additional subpopulations of focus.

13. Establish formal and informal feedback loops with patients and the care team.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: care team.

To help ensure that your practice’s ideas are meeting the needs of patients (and their families), helping to reduce identified equity gaps, and are feasible/sustainable for your practices, it is important to have both formal and informal feedback loops.

For patients (and their families), feedback loops might include:

- Sharing ideas with the population of focus to gather feedback and ensure accuracy before testing.

- Getting feedback from patients directly after testing new ideas with them (and incorporating their feedback into your next test).

- Patient satisfaction surveys (or similar).

- Follow-up calls with a subset of patients to understand what works well and what could be improved.

- Patient focus groups.

- Having the practice’s patient advisory board or similar provide feedback.

- For the care team, feedback loops might include:

- Existing or new staff satisfaction/feedback mechanisms.

- Regularly scheduled meetings/calls to get staff feedback on processes, methods and tools.

14. Continually analyze your data to determine if your efforts are closing equity gaps.

Suggested team member(s) responsible: care team.

This includes regular (at least monthly) review of the stratified measures for all of the following:

- Core measures for the population of focus.

- Supplemental measures for the population of focus.

- Process measures for the population of focus.

- Social needs data.

- Any additional measures collected as part of your testing and refinement effort.

Share the data with patients to both show your work to decrease known equity gaps and to solicit ideas for closing them.

Implementation tips

- When testing a change idea (either a key activity or new idea) for your practice to address a known equity gap, the size of your test scope or group is critical.

- We recommend starting with a very small test (e.g., with one patient or with one clinician) or a small test (e.g., with all patients seen during a three-hour period by one clinician) unless you are certain that the change idea (key activity or test) will lead to improvement (with little or no adaptation for your practice), the cost of a failed test is extremely low, and staff are excited to test the change idea.

- As you learn from each test what is (and is not working), you can conduct larger-scale tests and tests under a variety of conditions. While at first glance this would appear to slow down the implementation effort, starting small and “working out the kinks” as you progressively work to full scale actually save time and resources and are much less frustrating for your patients and care team. The visualization below provides guidance on how big your test should be.

FIGURE 10: HOW BIG SHOULD MY TEST BE?

Resources

KEY ACTIVITY #5:

Expand Clinic Hours Outside of a Typical Work Day

This key activity involves all seven elements of person-centered population-based care: address social needs.

Overview

Clinics may take many approaches to provide person-centered access to care. A potentially transformative approach is to offer appointment times outside the typical workday. For example, you may choose to offer appointments at early morning hours or evening hours at your clinic a couple of days a week, as needed.

Telehealth technology may also be used to supplement and provide flexible hours, since staff may be more able or willing to work early or late hours from their homes.

Patients need accessible healthcare to ensure that they have access to care that meets their needs. Many health center patients work one or more jobs and often have limited time to attend medical visits during what are considered typical business hours. Flexible clinic hours can expand patients’ access to care and could be a good match for staff preferences as they balance work and life responsibilities.